Adams: I’ll Bring Open Streets To Neighborhoods With Most ‘Urgent’ Need

He’s open to doing better.

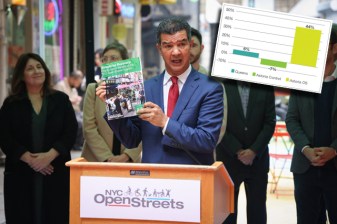

With the Department of Transportation defending its open streets program after a devastating new report on its shortcomings, presumptive mayor Eric Adams said on Tuesday that he’ll bring the city’s open streets program to neighborhoods that have been routinely left out of the vital safety and environmental improvement program.

“We need a real system, a mapping system to show show us in real time where the DOT is building to make sure that it’s equitable,” Adams said at a campaign stop on Tuesday afternoon. “It’s going to come from me. You are going to make sure that you look at all these communities, we’re going to judge by high illness rates, higher asthma rates, high diabetes rate, high heart disease rate, once we know where the rates are, that is what we should be going first.”

Adams’s plan for how he’ll strengthen the open streets program comes as the city DOT claimed a major inaccuracy in the and Transportation Alternatives new report that the city’s open streets program is failing low-income, Black and Latino neighborhoods because the open streets in those communities are overwhelmingly open to cars instead of people. The TA report, which was based on the work of volunteer surveyors who the organization said visited every listed open street in the city, claimed that only 126 out of 274 listed open streets were “active” — and amounted to a mere 23.89 miles, far below Mayor de Blasio’s promise of 100 miles.

Beyond the mileage shortcomings, the report also found:

- Open streets in the Bronx and Brooklyn were graded worse than the citywide average across the five boroughs. On a scale of 10 based on how many attributes an open street had, the average open street in the Bronx got 2.0 out of 10 and the Brooklyn average was just 4.1 (the citywide average was 4.3).

- Households with an income under $50,000 are significantly more likely to live near a low-rated open street while households with an income over $100,000 are significantly more likely to live near a high-rated open street.

- The streets that are considered active had much better ratings: Active streets in Queens and the Bronx were rated 7.3 and 5.7 respectively, but the total active open street mileage was just 6.3 miles for Queens and .53 miles for the Bronx.

- Even though Manhattan and Brooklyn combine for 48 percent of the city’s population, the boroughs combined to have 66 percent of the active open streets.

But the DOT said that its own data shows that there are 47 miles of active open streets across the city, a number that’s higher than the report says but still less than half of the promised total for the program.

“We actively and frequently checks on the status of our Open Streets, and we’re confident that a lot of these streets are, in fact, operational — despite what a canvasser might have seen on one isolated visit,” DOT spokesperson Alana Morales said. “There are also open streets that were recently updated on our maps, which wouldn’t have been counted in TA’s report.”

The idea Adams put forward is not far from a recommendation Transportation Alternatives made at the end of the new report. The group recommends that the city start with an audit “that tracks historic and modern spending on city streets by neighborhood, overlaid with rates of speeding, traffic violence, asthma, air quality, and access to green space” before determining which neighborhoods are most in need of the extra outdoor space.

The mayoral candidate and Brooklyn Borough President did not limit his comments to how to best install open streets equitably, promising that he’d take responsibility for bringing other street safety infrastructure to the entire city, something he’s done previously such as his endorsement of a bike lane on Classon Avenue in the face of local political opposition.

“We need to map the city. We need to make sure that the pedestrian plazas, green spaces, how we spend our dollars on parks, we need to make sure that it’s done in an equitable fashion. And part of our overall health plan is built into making sure we have those open streets, make sure we have the bike lanes built out, make sure we have pedestrian plazas done in an equitable fashion as we deploy them,” Adams said.

The suggestion that Adams will also pay more attention to how pedestrian plazas are installed could save lives in the future if his administration follows through. Last month, a 3-month-old baby girl was killed by a reckless driver who drove the wrong way up a small stretch of Gates Avenue that could have been turned into a pedestrian plaza during a redesign, but the city instead kept the slip street open to vehicles in order to preserve six parking spots.

Reports from surveyors and open streets volunteers suggest that the program needs more of a jolt of energy and interest than the DOT’s defense provides, as Bronx resident Lucia Deng demonstrated this past summer when she found only one active open street out of 13 she visited in her home borough. The Bronx was the borough that the report said suffered the most from neglect by the city, with a whopping 84 percent of listed open streets graded as inactive.

Pt. 2. Only ONE out of 13 designated Open Streets I visited yesterday in the West & South Bronx (miscounted in the video ?) were actual #OpenStreets! How can we get more outreach & resources to our community to change this?? pic.twitter.com/cv0kHmExkm

— Lucia 😀 ? (@LuciaDLite) July 20, 2021

In north Brooklyn, on open street steward said the city was working to support one open street while shying away from assisting one where there was a very literal high-profile theft.

“North Brooklyn is still waiting for our replacement barriers for Driggs and Russell,” North Brooklyn Open Streets Community Coalition member Noel Hidalgo said, referring to the barriers stolen from Driggs Avenue and Russell Street by an allegedly imposter Amazon delivery man in April. “On the other hand, the DOT has committed resources for Berry Street,. The City Cleanup Corps is maintaining and staffing it, so there’s more resources going to one of the city’s longest open streets.”

Hidalgo also said that even a positive example like Berry Street can be exhausting to keep going under the current setup.

“Even on Berry Street, it takes a lot of volunteer labor, it takes a lot of time a lot of coordination and that can be very grating and draining,” he said.

A visit to a pair of open streets near schools on Tuesday also yielded mixed results. A listed open street on St. Marks Place between Classon and Grand avenues in Brooklyn did not reveal any evidence that this open street ever existed. But an open street on Underhill Avenue between Atlantic Avenue and St. Johns Place had barriers up at every intersection, but in such limited numbers that drivers could access the street easily. In five minutes of observation on the corner or St. Marks and Underhill, five drivers went around the barricades.

For their part, Transportation Alternatives defended the data from its surveyors , and argued that the report used a generous definition of what made an active open street (one volunteer seeing a barricade in the street during the timeframe when the DOT listed the street as an open street).

“Our report is based on 791 survey results, including at least one survey from all 274 open streets, by more than 350 unique volunteers who went to each site to see the on-the-ground conditions,” said Transportation Alternatives Communications Director Cory Epstein. “The de Blasio administration can have a list showing more miles of open streets, but with all of the failures of equitable implementation so far, what matters is what is active on the ground. We invite the administration to travel to all open streets locations and ensure they are properly functioning, meeting the needs of neighborhoods, and supporting New York City’s recovery. … New Yorkers deserve better.”