OPINION: New York Leaders Face A Crisis of Their Own Making After Killing of Jordan Neely

Help wasn’t on the way.

Nearly four years have passed since disgraced ex-Gov. Andrew Cuomo, capitalizing on sensationalized media reports that homeless individuals were causing subways delays, called publicly for the MTA to address “the increasing problem of homelessness on the subways.”

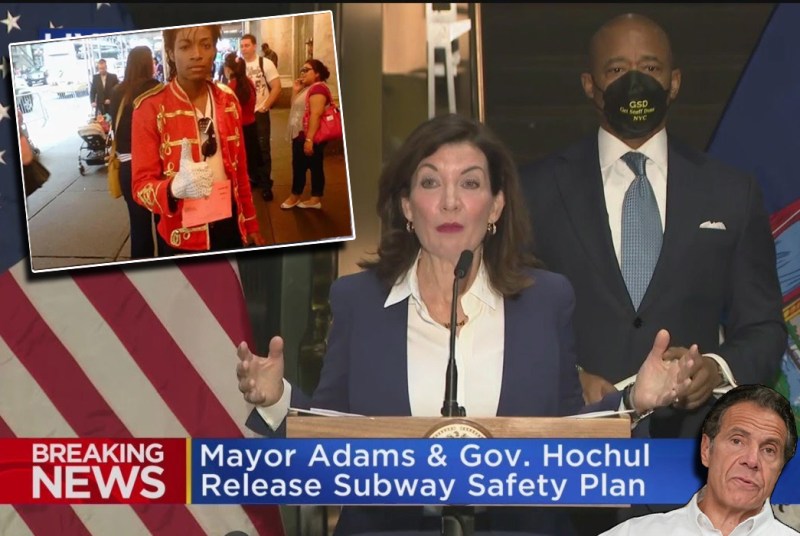

It’s been a year and four months since Mayor Adams stood alongside Gov. Hochul and pledged “to utilize our police to do public safety and our mental health professionals to give” people living on the subways “the services that they need.”

That’s not exactly what happened. The mayor spent his initial months in office buckling to community opposition and canceling several of his predecessor’s planned homeless shelter projects, including two proposed “safe haven” facilities in Chinatown — the kind that provide services needed by an unhoused person experiencing mental illness. The shelters would not have been far from the Broadway-Lafayette subway station, where Jordan Neely, who appeared to be having an emotional breakdown, was murdered by a man who put him in a chokehold on Monday.

City-funded supportive housing, meanwhile, continues to be inaccessible for thousands of people who need it, City Limits has reported. From June 2021 to the end of July 2022, just 16 percent of supportive housing applicants received a placement, according mandatory data the city released for the first time last year [PDF].

More disturbing: Over half of applicants weren’t even referred for placement interviews, while 254 applicants who did get interviewed wound up rejected because the publicly funded supportive housing provider claimed they could “not provide the level of service needed.”

“If the wealthy people of New York City want to feel like they can walk down the street and take their kids to school and stuff, you know, the price is to pay attention to these issues and these people who need help,” said Meg Floss, a supportive housing advocate with SHOUT.

“The funding already exists, it’s just not being used. It comes down to a horrible mix of incompetence and corruption,” Floss added. “And there is corruption, because people are being paid to do something they’re not doing. The amount of money these shelters make is astounding. What kind of operation are you running that you’re a supportive housing provider and you can’t meet their needs?”

MTA's fall rider survey asking once again how satisfied I am with people behaving erratically and experiencing homelessness on trains pic.twitter.com/CTCDx9NM44

— Kevin Duggan (@kduggan16) November 21, 2022

All of that should be irrelevant to the killing of Neely, whose presence in public was not a crime and certainly not one punishable by death. Yet the presence in public of people like Neely is exactly how Cuomo, Adams and other Big Apple policymakers have framed the issue of subway safety.

“We listened to the public on what they wanted and we incorporated into our strategy. And they’re telling me, ‘Eric, we’re seeing less homeless on the system. We are seeing the police officers,’” Adams said at a “mission accomplished” press conference with Hochul earlier this year.

After an unhoused, mentally disturbed man killed Michelle Go in Times Square in January 2022, MTA leaders posted photos of homeless people at their monthly board meeting and ran through a list of rider complaints about “people behaving erratically” and “making them feel uncomfortable or unsafe.”

“Our customers don’t feel safe on the subway. They’re afraid,” then-Chief Customer Officer Sarah Meyer told board members. “Our customers care about our city, our transit system and their fellow New Yorkers and it breaks all our hearts to see pictures like this.”

Meyer went on to quote the experience of a rider named “Randy.”

“I cannot be the only person who believes that New York City’s subway crime level is out of control,” Randy allegedly wrote. “Most of my colleagues avoid taking the subway because of crime, violence, and mentally ill people.” (Subway ridership has risen since, and is now at over 70 percent of pre-pandemic levels, according to MTA stats. NYPD figures show crime has also dropped.)

Officials’ stated empathy for the people suffering mental illness in public spaces like the subway is all well and good, but their goal for years — beginning with Cuomo’s 2019 declaration that “the number of homeless people” was “directly impacting service” — has not been to help those people, but to get them out of the way.

“The vast majority of them mean no harm to anybody and and it’s just heartbreaking to see people in that condition,” MTA CEO Janno Lieber said at that same January 2022 meeting. “But there are also some folks whose behavior and the way they were conducting themselves, you know, will be alarming to other riders. … This is a serious situation we have to deal with.”

There will be more “folks whose behavior will be alarming to other riders,” of course. Those types of behaviors are an eternal fixture of public space.

The truth is that despite high-profile exceptions, the homeless are much more likely to be crime victims than criminals, according to the federal government. The country has seen a recent surge in murders of unhoused people. Yet for four years our elected officials and their appointed MTA leaders have engaged with homelessness as a matter of “customer” relations.

We should want to be a city of people that responds to desperation with compassion and care, and not fear. Four years of scaremongering about the homeless made us something else.