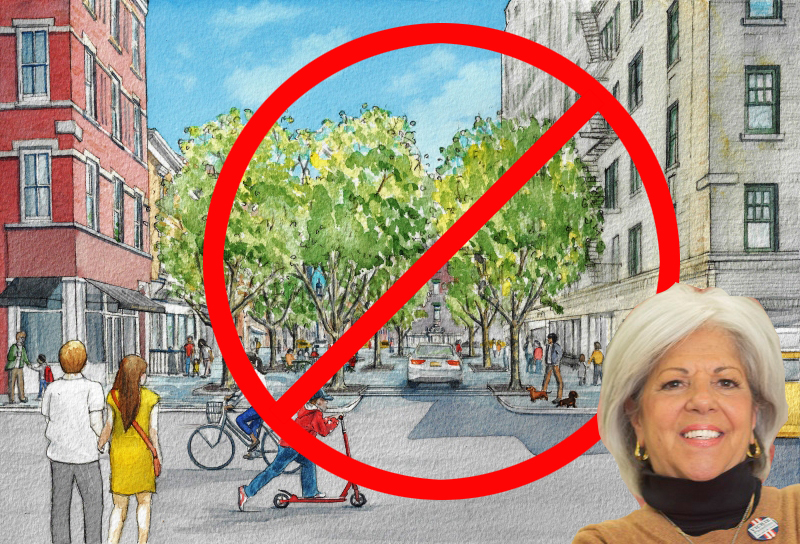

Op/Ed: Council Member Decries the Livable Streets Movement as ‘Radicals’

Editor’s note: Last year, Queens Council Member Vickie Paladino willfully antagonized the safe streets movement and activists with a pair of tweets that seemed to mock or at least question the motives of those who seek to make communities more livable and to reduce the numbers of people killed in crashes every year. The first tweet claimed that “radical bicycle activists … dictate transportation policy unilaterally.” The second tweet said that Adams administration policy “is now just a verbatim wishlist from the worst sort of misanthropic radicals on the fringe of the conversation” about transportation in New York City. Both of these statements are demonstrably and egregiously false. But given that Twitter is a terrible place for reasoned discourse, we reached out to Paladino asking her to clarify her positions. She said she’d be happy to.

We were cautious; as much as we believe it’s crucial for all voters to know how local elected officials think, we were nervous about giving a voice to someone as consistently reckless as Paladino, who has offered blatantly false statements on a number of public issues beyond transportation. As one city spiritual leader cautioned, even if we annotated Paladino’s op-ed with detailed fact-checking, it might not be enough because her thoughts would still be out there: “What you put in the world, exists in the world,” the person told us.

So we issued some caveats:

1. Council Member Paladino retweeted a link to this story with the comment, “How did a tiny niche of radical bicycle activists manage to achieve such influence that they basically dictate transit policy unilaterally now? Like, there is zero debate on this issue. The die seems to be cast, yet I have not met a single normal person in favor of this.”

QUESTION: What “issue” is she talking about? In the article, the commissioner was talking about how he wants to make roadways safer for all users. Does CM Paladino oppose this?

2. She then tweeted, “There exists a WIDE spectrum of opinion on the issue of public transit, cars, and bike lanes, and how our city should operate in the future. Yet our official policy is now just a verbatim wishlist from the worst sort of misanthropic radicals on the fringe of the conversation.”

QUESTION: Who are the “misanthropic radicals” to which she is referring and what does CM Paladino believe is that group’s “wishlist”?

3. The tweets suggest that CM Paladino thinks there is a better way to get people around. Currently, her district has among the fewest bike lanes and bus lanes, and buses average just 7.8 miles per hour. And close to 30 percent of district households do not have access to a car.

QUESTION: Can you provide us with the Council member’s “transportation” plan?

4. According to city stats, so far this year, there have been 1,421 reported crashes in her district, which is more than four every day. Those crashes injured close to 600 people, or roughly two every single day: 25 cyclists, 75 pedestrians and 497 motorists. Three pedestrians were also killed in her district.

QUESTION: Does CM Paladino think this is alarming and, if so, what does she believe is the best way to make roadways safer?

5. Three pedestrians have been killed in CM Paladino’s district since she took office. One victim has not been identified. But the other two are. Both were killed by drivers:

1. Jose Tejada, 58, of 121-27 Eighth Avenue, Queens, killed on Oct. 19 by the driver of a 2006 Dodge Caravan.

2. Genci Frasheri, 70, of 160-15 Powells Cove Boulevard, killed on Nov. 14 by the driver of a 2021 BMW.QUESTION: Has the Council member reached out to either family? If so, what did she tell them? If not, what would she tell them?

The resulting 2,600-word magnum opus did not address any of our questions specifically, but we are running her op-ed nonetheless, along with a corresponding piece by activist Doug Gordon that debunks each and every one of her profound misstatements and outright lies. But to clear the record, here is Paladino’s piece, unedited.

New York is always changing. The city of 50 years ago was very different from what we know today, and nearly unrecognizable from 50 years prior to that. Much has improved. Although some would argue that we’ve taken more than a few wrong turns along the way.

So change is a constant in New York, that much is true. However, as good citizens and elected officials, it is our responsibility to ensure the changes which take place during our stewardship not only serve our immediate needs, but also ensure the safety, prosperity, and viability of our city for future generations.

To that end, the question of our transit mix has become a hot topic of discussion, with influential and energized activists and urbanists pushing for radical changes to transit policy they feel very strongly about, and many ordinary citizens feeling left out of the debate entirely.

Recently, I weighed in with a tweet that got quite a bit of attention amongst the online activists and urbanists, calling attention to the simple fact that many New Yorkers feel left out of the debate and powerless thanks to perceived collusion between activists, special interests, and regulators.

This tweet was almost immediately swarmed by the activist/urbanist community— as is common with any tweet posted by nearly anyone which argues against their orthodoxy.

The goals of these activists are clear, unambiguous, and radical; the elimination of private vehicle ownership in NYC, and the closing of most city roads to any vehicle traffic at all.

It’s hard to pretend otherwise when it’s plainly written in most of their twitter bios, and they’re not particularly shy about saying it at every available opportunity.

And when regular people see every major proposal and action by our DOT and lawmakers moving us closer to exactly that — from congestion pricing to “open streets” to the intrusion of bike lanes even where they make no sense — it’s hard to draw any conclusion other than the long-term policy goals of our regulators are being essentially dictated by a rather insular and militant activist community with radical (and unfeasible) ideas.

While it’s true that NYC has some of the lowest rates of private vehicle ownership in the country — around 50 percent according to most accounts — there is far more complexity to that figure than the activists would like us to believe. Activists (including Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine) repeatedly cite the 50-percent figure as definitive justification for their overall agenda. But it’s deeply fallacious to assume that every non-car- owner in NYC is completely on board with the notion of banning cars and closing off most city streets to vehicles entirely. And it also assumes that the four million people who do own cars simply don’t matter and deserve to be squeezed in every possible way.

In fact, there is very little actual data on how New Yorkers as a whole feel on the issue of our future transit mix, and I suspect this is deliberate. The assumptions are a comfortable fiction for those steering this policy. Actual data would only muddy the waters and force activists, regulators, and lawmakers to contend with the more complex realities of public opinion. Nevertheless, I would love to see a broad, deep, and unbiased public opinion study of New Yorkers to get a more nuanced appraisal of where they stand on transit issues and how they’ve been impacted by changes made thus far.

Most of this activist energy is promoted (as, historically, so many questionable ideas are) under the guise of safety. “Safe streets” is the banner they fold it all into. Who could be against that? Well, nobody. We all want safer streets. And there is a lot of work to be done there. However, the only answer the activists seem to be interested in is the forcible reduction and eventual elimination of cars, at first by making their ownership and operation prohibitively expensive, and eventually through regulatory action. By that logic, we could also eliminate plane crashes by banning air transport, and we could eliminate cyberbullying by banning computers. There are no simple solutions to complex problems, and “ban everything” usually makes for terrible policy.

Speeding, reckless driving, and unaccountable drivers are a huge problem in this city — and in my district as well. I am not going to make excuses here; things need to improve. However, there are solutions to this problem which don’t involve nuking the entire concept of private vehicle ownership or making life even more expensive for the average working person.

I am very much in favor of speed bumps, grooved pavement, and speed tables/raised pedestrian crossings to keep speeds down, particularly in residential areas like the ones found in my district. Ideally, I would love to see some form of passive speed control on a great many residential streets in the district I represent — and I imagine passive speed controls could be implemented on side streets throughout the city. Making it physically/mechanically difficult or even impossible to speed is ultimately worth far more than all the tickets in the world — if safety really is the goal. These passive systems also have the added benefit of being relatively inexpensive, easy to maintain, and place no financial burden on the community. I have also been working to install additional traffic controls in my district, like stop signs and traffic lights in problem areas as a more immediate fix.

I am also very much in favor of enhanced traffic enforcement by the NYPD citywide. There is no substitute for the traffic stop, both in terms of ensuring driver accountability and deterrent factor. However, as much of our other quality-of-life enforcement has been suspended thanks to “progressive” ideas about limiting the scope of law enforcement, so has traffic enforcement to a large degree, and we are suffering for it.

In fact, San Francisco — always a good barometer for the vanguard of progressive thinking which also animates much of our policy here in NYC — has moved to abolish traffic enforcement entirely. This seems counterproductive, especially coming from people who ostensibly want to promote “safe streets.” And quite radical.

What I am not in favor of are the proliferation of speed cameras, which have proven over the years to do very little to deter speeding or reckless driving, and in fact serve mainly as revenue generators disproportionately impacting the working class. A speed camera can only deter those who already care about obeying the law — and only penalize after the fact. This is not doing much to actually make streets safer in any appreciable way. I realize that these cameras may have their place, but they are not at all suited to be anything close to a primary means of enforcement, which is how they are increasingly utilized.

Cameras are also easily defeated by criminals who either conceal their plate or use fraudulent plates — allowing them to operate with impunity, free to break our traffic laws and wreak havoc either in cars or on unregistered and illegal motorcycles, dirt bikes and ATVs. We’ve all seen cars with defaced or fake paper license plates, as well as the gangs of dozens (and often hundreds) of ATVs tearing down our streets, blowing through red lights and generally causing chaos and even attacking pedestrians. The only solution to this, of course, is old-fashioned law enforcement, which activists don’t seem very interested in talking about. But actual accountability will be crucial if we want to realize ‘safe streets’ in NYC.

The biggest mistake these activists make, however, is in their apparent misunderstanding of what roads exist for. They talk about roads as though they’re currently a species of luxury accommodation for the wealthy and selfish, filling no practical purpose other than to serve the ego of drivers and subsidize ‘big oil’ — and easily replaced with bicycles and parks, if only we had the courage and political will to just make it happen. They speak in terms of roads being reclaimed ‘for the people’ or some other such pablum.

Let me make one thing perfectly clear: Roads are an instrument of commerce, first and foremost. Period. They exist to allow the flow of goods, services, workers, and customers into and out of our commerce centers so as to maximize the economic potential of our city. This has been true from the days of the Romans onward, and it will remain true for the foreseeable future. This is why we have roads.

All discussions about the future of transit must be centered around maintaining the viability and expansion of commerce, or we will be writing the death warrant of our city. It’s that simple. Without commerce, our city dies.

That’s not to say there aren’t more innovative ways to move goods and people around, but historically it has never been terribly smart economics to place serious internal, artificial limitations on how people move, or to make it prohibitively expensive to do so. However that seems to be a major part of the plan for our future — to price most private and commercial vehicular traffic out of the transit mix via congestion taxes, arbitrary camera enforcement, and other regulatory disincentives, and to close more and more streets entirely.

Furthermore, activists relentlessly fetishize small European cities like Copenhagen and Amsterdam, where they see the bicycle as a primary mode of commuting, and insist — loudly and to anyone who sits still long enough — that this is definitely the future of NYC, or else. The bicycle has taken on the role of religious totem with these people, and a quick perusal of social media reveals a cultish obsession with cycling and codifying their hobby into the infrastructure of our city no matter who objects or for what reason, with the ultimate goal of supplanting private vehicle ownership with bicycles for the masses. Aside from the utter impracticality, it all comes off as deeply weird as well.

However the very simple reality is that Copenhagen has a GMP of $400 billion. The GMP of Amsterdam is a paltry $64 billion. And the GMP of the New York City metro area is $1.5 trillion. I’m sorry, but you aren’t going to sustain a $1.5 trillion dollar economy with bicycles, closed streets, and positive vibes. Math doesn’t care about your hobby, or your politics.

There is more than a whiff of privileged detachment to all of this. It takes a certain type of coddled affluent professional who’s never really interacted with an outer-borough working person to believe any of this is reasonable, to disregard offhand any and all objections — and then to have the political clout and financial resources to actually move the bureaucracy accordingly.

This is how we end up with bike lanes where they absolutely do not belong, disrupting the lives of working-class people and small business owners who’ve been there forever. This is how we end up with highly educated and well-paid elites screaming on the internet about the ‘injustice’ of a delivery van double-parking in a bike lane for a few minutes. This is how we end up with entire apartment blocks suddenly cut off from all emergency services by ‘Open Streets’ with zero regard for elderly and disabled residents. This is how we end up with college students and the white-collar laptop class lecturing plumbers and construction workers and truck drivers about ‘workers rights’ and rambling about cargo bicycles.

Please do tell the the blue-collar workers who make their living coming in and out of the city every day about how feasible it is for them to pack up their tools and equipment onto a bicycle or subway car, or that they deserve to pay $100 daily for the privilege of driving onto the hallowed streets of Manhattan each morning in order to toil on behalf of the benighted class who are not bothered by such things. And then wonder why ‘bike lane activist’ has become an epithet.

This is not to say that bike riding isn’t a good thing, or that bike lanes don’t have their place either — riding a bicycle is a healthy and positive hobby for those whose lifestyle and occupation allow it. And there are parts of this city where bike lanes might work great for the local population to get around. This is a big, diverse city with a lot of differentiation between neighborhoods and populations. The fact is there is no one-size-fits-all solution to our transit question, and local control via transparent community input, canvassing, and a comprehensive review process in which all stakeholders have a voice is what’s best. But this has simply not been the case for the most part, up until now. These decisions have been largely top-down, opaque, and often at the expense of long-time residents by a gentrifying population. And the activist/urbanist position is inflexible — bike lanes and open streets are for everyone, everywhere, with no exceptions. This is just not realistic, and promotes only for rancor and hostility.

Additionally, there must be accountability for cyclists on par with drivers. I would propose that in order to operate a bicycle or e-bike on a public bike lane, riders must be licensed by the city, pass a safety course, wear approved safety gear like a helmet and padding, register their bike, display a license plate which can be read by cameras, and carry liability insurance to protect against property damage and injuries. If it’s going to be a long-term fixture of our transit mix, biking can no longer be a free-for-all. It must come under the same regulatory apparatus as any other vehicle. Period.

Additionally, it would only make sense that a cycling permit be required to access the Citibike system as well. A digital permitting system would make it fast and easy to check out a bike, but it would be crucial in guaranteeing the safety and security of riders and those they share the road with.

I would propose these regulations only for those utilizing bike lanes on public streets. Riding a bike in a residential neighborhood or in public parks would be unaffected. But these bike lanes and their users must be regulated for the sake of public safety and they must begin to contribute financially to the infrastructure and upkeep they demand.

I’d also like to see additional investments in public transit — our subways and busses continue to be the main arteries of our city, however ridership is not where it should be. Much of this is due to deteriorating public safety, but much is also a result of poor planning and fiscal mismanagement. When I first came into office, one of the very first things I faced (on my first week, I believe) was a disastrous redesign of bus lines that negatively impacted the heavily immigrant working-class area of College Point — the very people who depend on them the most. It’s not entirely an issue of funding, but a comprehensive independent audit of the MTA is long overdue.

Overall I think we have a good opportunity at this time to plan for a future transit mix that works for everyone, and leaves our city well-positioned for the coming years. But only if we are realistic, pragmatic, and free from ideological blinders. Understanding that what works well in some areas for some people may be anathema to others, and that our overriding goal must be the continued financial viability of our city above all else, will be key to designing and implementing a system that truly works for today and future generations. Transparency, accountability, and community input will ensure everyone feels that their voice is being heard; many want to see big changes and want them quickly, but reality demands a careful and deliberate process that accounts for much more than the instant gratification of activists.

I want to thank Streetsblog for the opportunity to publish this op-ed. It speaks very highly of the editors to give an opposing viewpoint this space.

Vickie Paladino, a Republican, represents College Point, Douglaston and Whitestone in the City Council.