‘Just Keeping the Lights On’: Low Morale, High Staff Vacancy Rate Hobble Department of Transportation

The upper ranks of the city Department of Transportation have been depleted by an exodus of high-skilled employees this year, reflecting mounting frustration among some staff members and making it harder for the agency to fulfill its mission, according to records and interviews.

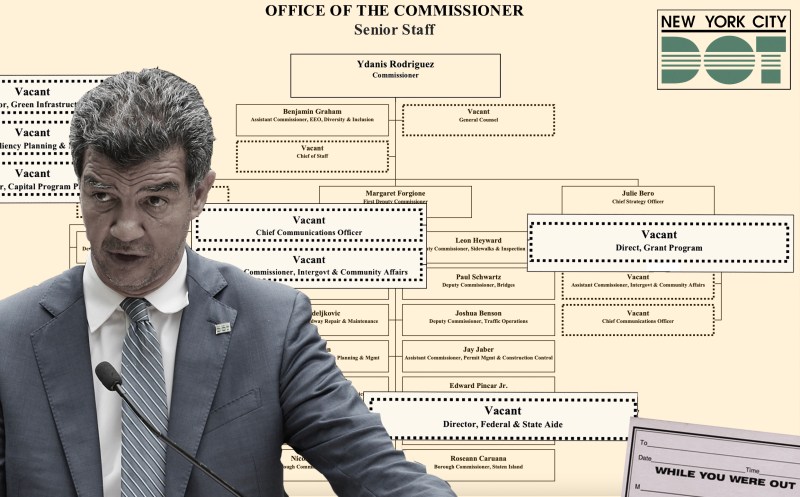

Among roughly 560 of the top positions at the agency, nearly one in five sat vacant in early September, according to the DOT organizational chart obtained by Streetsblog through a Freedom of Information request. That’s higher than the DOT-wide vacancy rate of 12 percent shown by City Council data from June, the latest figures available.

The organizational chart reveals many high-level departures this year — the first of Ydanis Rodriguez’s tenure as transportation commissioner — including chief of staff, general counsel and the head of intergovernmental and community affairs. Turnover is common at the beginning of a new administration — especially in top positions — but other key posts that were empty earlier this month were also empty at the beginning of the year, according to interviews and a prior organizational chart. Those positions include director of communications, director of automated enforcement and director of federal and state aid.

The departures have left some remaining employees overworked and demoralized as they struggle to carry out the agency’s vast array of responsibilities amid persistently high rates of traffic violence in the city, according to interviews with a dozen current and recently departed staffers, nearly all of whom requested anonymity to speak candidly about their experiences.

“We got to the point where we couldn’t produce anything new,” said one recently departed agency employee. “We were just keeping the lights on.”

Not all of DOT’s problems are unique to the department. Agencies across city government are struggling with high vacancy rates — some more than DOT — according to Council data. That trend stems from a hiring freeze during the pandemic’s first year; a wave of resignations after the city required municipal employees to return to the office five days a week; a policy requiring agencies to let two jobs go vacant before filling one; the city’s slow hiring process; and the lure of the private sector, where salaries are often higher and schedules more flexible.

But some of DOT’s woes are entirely its own. Recently departed employees said staffing constraints are delaying street improvement projects and making it hard to meet street safety benchmarks. Other current and recently departed employees voiced dissatisfaction with alleged political meddling in street safety projects and with the leadership of Rodriguez, whom some described as well-intentioned but unqualified to lead the $1.3-billion agency.

“I think his heart’s in the right place, but he has no idea how DOT works,” one current DOT official said of Rodriguez. “He’s learning. But that’s not what you want. You want someone who’s a Janette or a Polly, who’s a transportation professional. Or someone who knows how to run a large organization. He’s neither.”

Former Commissioners Janette Sadik-Khan and Polly Trottenberg oversaw groundbreaking projects while leading DOT from 2007 to 2020, including the pedestrianization of Times Square, the creation of Citi Bike and the adoption of Vision Zero.

The agency declined to make Rodriguez available for an interview.

In a statement, DOT spokesman Vin Barone said: “Our passionate team is working every day to execute Commissioner Rodriguez’s ambitious agenda to deliver a safer, healthier, and more sustainable city with a clear focus on providing investment and resources equitably to historically underserved communities. As New Yorkers continue to lose their lives from traffic violence, the administration is investing a historic $900 million in the New York City Streets Plan and has outlined a plan to redesign 1,000 intersections this year that we remain on track to complete on time.”

Projects delayed, watered down

DOT was a gratifying place to work for one former employee who spoke to Streetsblog — at least for a while. During her years at the agency, her division, called Transportation Planning and Management, oversaw the ambitious redesign of major streets, the creation of new public spaces, and the expansion of the city’s bike lane network. The division was robust, she felt, and its work was impactful.

But that changed during the pandemic, the staffer said. After former Mayor Bill de Blasio required city workers to return to their offices last year, people started quitting DOT and not getting replaced, she said. Suddenly there was a huge shortage of civil engineers — the DOT employees responsible for producing the technical drawings necessary to build street improvement projects. It now took months longer than usual to receive those technical drawings. When they finally were finished, new shortages on the crews that built the project set timelines back further. Some building materials were in scant supply now, too, like the green paint for bike lanes, meaning new lanes would sit unpainted for months, she said.

So projects would get shelved until the next year, she said, or finished with half-measures, like curb extensions delineated with paint and plastic posts instead of with concrete.

“We have so many projects that are really good and ready to go, and they just can’t go in, which means the agency’s ability to respond to severe injuries and fatalities is also limited and slow,” she said.

So she left. She now works in the private sector, where she makes $30,000 more annually. And she can work from home.

The staffer’s experience is not unique. Across DOT, current and recently departed employees described a cycle: staffing deficits leaving remaining employees stretched thin, making it harder to meet agency benchmarks or delaying projects entirely, which hurts morale, which causes more employees to leave.

Many of the staffers who left this year are hard to do without. The chief of staff works to ensure the commissioner’s agenda is implemented throughout the vast bureaucracy of the department (an interim chief of staff is currently in place). The general counsel oversees all legal matters, like coordinating with the city Law Department on the numerous lawsuits DOT faces each year, from slip-and-falls to suits against major DOT initiatives. The head of intergovernmental affairs is the agency’s chief liaison with elected officials and helps craft DOT’s legislative agenda.

Another former Transportation Planning and Management employee said she left this year because she was sick of agency higher-ups watering down safety improvement plans for dangerous roads to appease opponents of the projects.

“It really jaded my view on transportation and policy and what actually gets put in the ground,” she said. She cited as an example DOT’s decision last year — under the previous administration — to nix a protected bike lane on a dangerous street in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, after local merchants complained about the loss of parking spots.

“It just seemed like people at the higher level don’t really care about street safety,” she said. “They care about appeasing the loudest voices in the room, whether that’s loud people in community board meetings or something the mayor wants.”

Working at DOT had been a dream job for her; she thought she would stay there until she retired. Instead, she left earlier this year.

Frustration with the commissioner

Rodriguez’s leadership at the agency has been a particular source of discontent for some current and former DOT officials who spoke to Streetsblog.

They acknowledged that Rodriguez appears passionate about wielding the powers of the agency to make streets safer and to make it easier for transit riders, pedestrians and cyclists to get around — particularly in communities of color that some feel have historically been overlooked by DOT.

But Rodriguez lacks the experience or expertise to lead the sprawling agency, they said. Before taking office, Rodriguez spent 11 years as a city Council member, including eight years as the chairman of the Transportation Committee. Council members typically have fewer than a dozen staffers. Rodriguez now leads an agency with thousands of employees.

Many characterized Rodriguez’s appointment to the top of DOT as a political favor from Mayor Adams. Rodriguez was a vocal supporter of the then-Brooklyn Borough President during his mayoral campaign last year.

Following the publication of this story, an Adams spokesman defended the appointment of Rodriguez.

“Commissioner Rodriguez came to DOT as a battle-tested champion for Vision Zero with a proven track record of delivering policy changes and resources to make our streets safer,” said the spokesman, who declined to provide his name. Rodriguez “has delivered in his first months as commissioner, laying out and implementing ambitious street safety plans, and Mayor Adams is confident he will continue to do so.”

In some ways, Rodriguez is still operating like a politician, not the head of a major city agency, current and recently departed DOT employees said. He is “obsessed” with media coverage, requiring members of the DOT press office to accompany him to even minor events and post photos of him online, according to former DOT official with knowledge of the current administration. (He has, however, kept the position of chief communications officer vacant, the organizational chart shows.)

And he has appointed nearly all of his Council staffers to positions throughout DOT, despite some of them not being the best candidates for the jobs, according to current and recently departed DOT officials.

And some said Rodriguez and Adams seem to formulate DOT policy based not on what in-house experts say will yield the best results, or on what’s feasible, but on what will make for good political talking points.

“He didn’t always listen to the technical experts. It was sort of like, ‘What’s the kind of showy thing we can do?'” one recently departed senior DOT official said. “He’s sort of out of his element in terms of really being able to think about the issues in a really critical and substantive way.”

The limitations of this approach have already become apparent, staffers said. Rodriguez and Adams promised to add barriers to half of the city’s plastic-protected bike lanes in their first 100 days — a pledge the agency then walked back. They vowed to improve visibility at 100 intersections this year by building bike corrals — only 65 were installed by Sept. 2, fewer than half at intersections, per DOT data. They also pledged to install 100 raised crosswalks a year; by Aug. 17, DOT had completed just eight, city data show.

DOT is also required by law to build 20 miles of new bus lanes this year. So far it has completed just two miles, according to the advocacy group Riders Alliance.

A DOT spokesman said the agency has “advanced many projects” under Rodriguez, including building protected bike lanes across the city, beginning a hotly contested road diet on Staten Island, and making busways in Queens and Manhattan permanent that had started as pilot projects under de Blasio. (One of those busways had its hours reduced.)

Gone backwards

After the city required workers to return to offices full time, one former DOT employee who worked in information technology watched his team shrink from 19 people to nine. As a result, he said, routine responsibilities — like creating web forms to enable residents to apply to DOT initiatives like Open Restaurants — took months longer than they had previously.

The team tried to hire replacements, but once job candidates learned they were on-site positions, the agency never heard from them again, he said.

“Not only were we struggling with the quality of the candidates that were applying, sometimes we couldn’t even fill them at all,” he said of vacant posts. “It hurts the quality of the service that the city’s able to provide.”

A DOT spokesman said that issues with web forms has not “delayed any specific initiative or announcement under this administration.”

It hasn’t helped that the city often offers new hires the lowest salary in a job’s pay scale, or that it can take months to onboard a new employee. With fewer employees, those who were left have had to do more, said Carmelo Mattina, who retired from DOT’s Fleet Services division in July.

“The replacements were not coming in fast enough,” he said. “Of course, the workload had to be done. So they just passed it on to all of us.”

The challenges facing DOT have left one senior DOT official who departed this year skeptical of the agency’s capacity to conceive and carry out the sort of innovative projects that defined its work under previous administrations.

“It doesn’t feel like that creativity or spark is there,” the official said. “I think we’ve kind of gone backwards.”

— with Gersh Kuntzman

Here is the full DOT org chart, as of the dates on each page: