ANALYSIS: ‘Permanent’ Open Streets Program Will Only Be As Good As The Next Mayor Wants It To Be

Meet Open Streets 2.0.

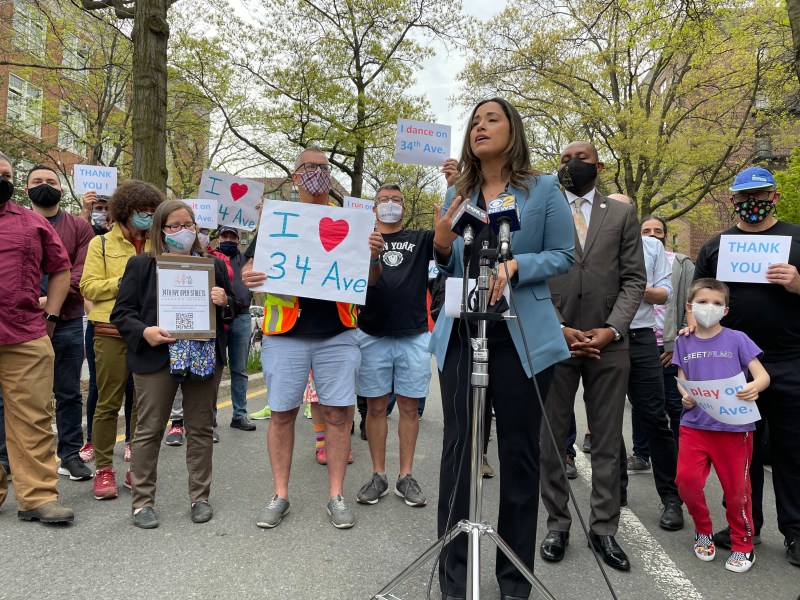

The city’s open streets program, an attempt to provide more space for New Yorkers stuck in their apartments and neighborhood limits during the coronavirus pandemic, was given a future direction on Thursday when the City Council passed a bill that makes the program truly “permanent.” The new law — which Mayor de Blasio has promised to not veto — lays out some specific new requirements for the Department of Transportation, but its success is still going to rely on the kind of work the next mayor and City Council want to put into it in order to prod the DOT into making a true citywide program that doesn’t just serve a few lucky blocks.

The law takes a light touch in certain areas, directing the DOT to create a process by which people can customize their open streets with more than just French barricades, as well as memorializing how the agency should determine which open streets applications should be approved. Per the new law, the DOT will have to take into account things like how open streets are already distributed around the city, the kinds of park access residents of the nearby blocks have and if a street is a bus or truck route.

Crucially, the bill allows for applicants to ask for open street setups that can stay up for 24 hours at a time. Typically, open streets that are not part of the Open Streets Restaurants program are open from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m.

What the bill doesn’t do is allocate specific amounts of funding for open streets, or set a benchmark for how many miles per year the have to be turned into open streets. And though the law requires the agency to issue a report on the program’s progress every year, it does not lay out exactly what the DOT should consider a successful open street when it studies the program.

The law, sponsored by Manhattan Council Member Carlina Rivera, continues to rely on a DOT that has ducked out of mandated obligations in the Vision Zero design standard law, which requires DOT to make a checklist of all possible road safety improvements it considered when redesigning a roadway. The problem? That bill (which became law without the mayor signing or doing much to acknowledge it) allows the DOT to simply present the checklist; there’s no accountability for why the safety improvements were not made. And even though Mayor de Blasio has said he supports the open streets law, it won’t go into effect until September, so implementing it will fall to the next mayor.

And because the law doesn’t put self-enforcing open streets first, it’s not going to quickly solve the issue of drivers feeling entitled to every inch of road space and the literal physical altercations that can arise from that entitlement. Yes, the new law commands DOT to conduct an annual review of the program and determine which, if any, open streets, can benefit from something more permanent such as a pedestrian plaza, the lack of metrics for that success means the city’s legion of safe streets activists (good evening, all) will continue to have to push to claw back every foot of streetscape from car drivers.

“The bill lays out the pathway forward, and a menu of options for the open streets to get better infrastructure become 24 hours,” said Transportation Alternatives Communications Director Cory Epstein. “What we need to do now is get more clarity on what that infrastructure can look like, push to to move quicker to get that infrastructure down and make sure they move more towards self-enforcing open streets, because the bill actually says if the infrastructure on a street is created in such a way that it doesn’t need to be staffed to push out barricades, you don’t need to have staff or an open street.”

If the next mayor is willing to put the heft of his or her DOT behind the law, it can turn into a useful tool to create a thriving open streets program, especially when it comes to creating open streets in areas that are underserved by the program.

Per the new law, the DOT is going to be responsible for managing or devoting resources to community organizations to manage at least 20 open streets in “areas underserved by open streets.” That mandate is designed to ensure that swathes of the city or neighborhoods aren’t left out of the open streets program, a shortcoming that was pointed out on day one of the program last year, and again weeks later, but never given a real solution.

“I want to make sure that we are going to some of these communities like Brownsville, East New York, South Harlem, and the North Shore on Staten Island,” said Rivera. “The community engagement piece and holding Department of Transportation accountable, that’s going to be my my number one priority, making sure that they’re going into communities that have said that they want something like this but just don’t have the resources to independently fundraise, to provide 10 volunteers at 8:30 in the morning. I want to make sure the elected officials are involved, but also some other community groups.”

Veteran activists and open streets volunteers urged the DOT to think outside the bun when it comes to who the agency thinks it can partner with — especially in a situation where the DOT is going to areas where a local Council member doesn’t have much of an interest in the open streets.

“The DOT will have to learn to communicate with a new set of neighborhood allies,” said Noel Hidalgo, who volunteers with the North Brooklyn Open Streets Alliance. “Youth advocates, housing advocates. there’s a great diversity of advocates in every neighborhood, and for a successful open streets, the DOT will have to learn to communicate with them.”

Hidalgo also praised the bill for taking a legal question out of the mix by mandating that the city be legally liable for the program, which Hidalgo said will allow new kinds of organizations to come in and make the open streets into lively community areas.

“With the DOT and city owning the liability, it makes it clear that a broader set of community partners can come in to not only staff but program the street. The critical thing is programming the street. What we’ve seen is when the street is programmed, the neighborhood likes it more than if it’s a traffic calming implementation,” he said.

For new areas to benefit from the program though, advocates said the city will also have to ensure its own outreach is working to inform and bring people in to the process.

“The main thing is that the application processes needs to be more accessible for people,” said Transportation Alternatives Director of Organizing Erwin Figueroa. “What I mean by accessible is it can’t only reside on an online portal. For communities that don’t currently have open streets, their outreach needs to be done in person, the DOT needs to be able to go out to the community and find community based organizations that could potentially maintained open streets.”

In a world where at least a pair of mayoral candidates have said that they’re willing to fund open streets with real resources, there’s also a fighting chance that the DOT can show, and promise, neighborhoods the kinds of environments and programs that Figueroa said the agency should be leaning on when it approaches new neighborhoods with an open street offer. (For now, Mayor de Blasio has pledged $4 million for barricades and programming, but that seems like a tiny amount of money in a big city.)

“If you just close a street, and people just see it as an empty space, there could be some people that might not see all these things you can do with it,” Figueroa said. “So now that we have a year of open streets, where groups like 34th Avenue, Loisada [on Avenue B], North Brooklyn and others have shown the kind of programming and activities that can be done on an open street, that should be something that the city should also present to those communities. Something like, ‘We can provide an open street, these are all the things that you can do and you can use open street for, and what are the things that you would like to do that we can provide support for?'”