THE STREETSBLOG INTERVIEW: Vax Daddy Huge Ma is the City’s Newest Bike Lane Advocate

New York City’s Vax Daddy has picked up a new moniker — meet your Bike Lane Daddy.

The 31-year-old software engineer behind the transformational website that compiled hard-to-find vaccine appointments after the city failed to create its own user-friendly site, is now hoping to channel his time and energy into advocating for better bike infrastructure — if only there was a vaccine to prevent traffic fatalities.

Huge Ma, the Astoria native who created TurboVax, is also, as it turns out, a safe-streets advocate — which he revealed earlier this month by posting on Twitter that he had biked to his own vaccine appointment at the Javits Center. He says he’s never felt safe riding in the city, especially next to massive trucks with no protection, or even in protected bike lanes that aren’t really protected — referencing the Crescent Street bike lane, near where a delivery worker was killed by the driver of a massive truck back in November.

“I’ve just been speaking about what I’m passionate about and transportation is one of them,” Ma said. “I was born and raised here. … With COVID and everything, bikes are becoming more and more prominent and a bigger part of our transportation system. I never feel safe when I bike. How could I ever feel safe in a regular striped bike lane? I’ve always got to be looking over my shoulder all the time. I’m always trying to find protected bike lanes, even some protected bike lanes are only so protected.”

Ma says the city is at a pivotal moment in its recovery where it needs to capitalize on the continuously growing bike boom that took off at the start of the pandemic, and finally return space currently dedicated for the storage and movement of private vehicles back to the people. Maybe Ma can again pick up where the city failed, but there’s no HTML code to fix the city’s poor bike infrastructure. There’s no bug in the system — except a lack of will.

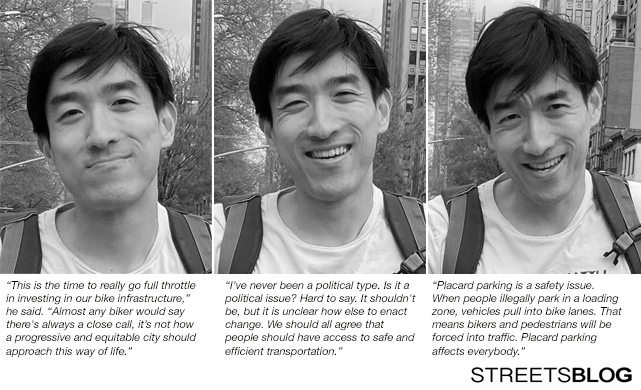

“This is the time to really go full throttle in investing in our bike infrastructure,” he said. “Almost any biker would say they’ve had a close call, it’s not how a progressive and equitable city should approach this way of life.”

Thoughts:

1) arm is sore

2) no red carpet?

3) Javits operation is a dream

4) we need some bike lanes around there because woof— Huge Ma (@turbovax) April 1, 2021

Bike lanes are still on my mind though…..check out this very safe and very protected bike lane that I took on my way to my mom's house! pic.twitter.com/ubsbHIBqkD

— Huge Ma (@turbovax) April 12, 2021

As a lifelong straphanger, Ma says he’s always been attune to the inequities of transportation in the city, but the pandemic merely shined a brighter light on them.

“Everyone now understands how transformative our streets can be to our lives, like open streets for example, and we need to really think about how we can make it work for the people — not necessarily one form of transportation,” said Ma, who moved back from San Francisco during the pandemic. “I’ve never been a political type. Is it a political issue? Hard to say. It shouldn’t be, but it is unclear how else to enact change. We should all agree that people should have access to safe and efficient transportation.

“With the subway shutdown in the evenings, how do people get around? Our essential workers need to get around,” Ma added, remembering Clara Kang, a 31-year-old nurse who was killed on deadly Third Avenue by a motorcyclist after finishing her nursing shift at NYU Langone Hospital–Brooklyn in October. “That was very sad to read.”

And unfortunately, it’s not just COVID that has made people weary of enclosed spaces like subways — even though data show it’s perfectly safe from the virus. Ma, who has been taking the subway his whole life, says that he and many of his Asian-American friends have now become more hesitant to take the train with the rise in hate crimes against Asians, many of which have happened inside stations and on trains.

“Another aspect, just for me as an Asian-American, there’s been a lot of violence recently and almost none of my friends take the train anymore, no exaggeration, almost none of them do. We are all city dwellers, been here for a long time — they don’t do it because they don’t feel safe and who could blame them?” said Ma. “So having bikes as a safe alternative is very top of mind for me, because not everyone can afford to have their own car or take Uber.”

Ma said he’s still taking the train, but fully recognizes that not everyone feels safe doing so.

“I still take the train, I don’t want to let the terrorists win. I’m still taking Citi Bike, using my personal bike, but I recognize that many other people, whether because of COVID or safety, they’re not willing to do that, and they need to be given a good alternative,” he said.

But biking on the streets of New York City comes with its own dangers — it’s not a choice one envies. Ma said he has experienced his own fair share of both racism and close calls with aggressive drivers, and a few times where those became intertwined. A few years ago, he said, he was biking in the Second Avenue bike lane where it meets the entrance to the Midtown Tunnel when a driver hurled racial slurs at him. Obviously, racism and road violence are not mutually exclusive, but Ma said it’s clearly a known dangerous intersection that invites that type of conflict.

“It’s an example where everyone knew from the beginning it’s a poor design and I’m lucky the guy didn’t run me over. He cursed me out, honked at me. I was taking the sharrows, which is shared with the cars, and he said, ‘Get the fuck off the road, you fucking c—-,'” Ma said, using a particularly offensive slur. “This is par for the course.”

Even after that encounter, Ma said he sees the problems with relying on police for traffic enforcement, especially for Black and Brown folks, who are disproportionately victims of police brutality. Ma said he supports moving to a system of automated enforcement to make streets safer, like advocates and pols have called for. That’s where tech could come in, he says.

“I think as we saw with Daunte Wright, it doesn’t really make sense for police to be involved in traffic enforcement — a lot of these things could be automated and a lot could be handled by civilians, for example, like speeding. Once it’s automated, it does away with a lot of the potential for corruption, the same with parking,” he said. “A lot of people in tech have a lot of hubris, like that tech can fix anything, but no, tech can’t fix everything. I’m open to ideas, for sure, I think there are many ways we can use tech to improve street life — not necessarily bike lanes. Tech has its own trade-offs as well, but I think it would be an advantage improvement over our current system where enforcement is handled by police.”

And in addition to bike lanes, Ma is all in on bus lanes —including on Flushing’s Main Street.

“They are a low-cost way of improving, and making our transportation more equitable. I’m from Queens and just looking at the map from a subway standpoint, it’s much less accessible. Bus lanes on Main Street are kind of a no-brainer,” he said, as a subtle dig at mayoral candidate Andrew Yang, with whom Ma has appeared, but whom he has not endorsed.

But in agreement with Yang (and in opposition to Yang’s mayoral rival Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams), Ma told Streetsblog that placard abuse and sidewalk parking by cops is an issue people care about — not only is it corruption, but it causes unnecessary danger.

“Placard parking is a safety issue. When people illegally park in a loading zone, vehicles pull into bike lanes or bus stops to offload goods. That means bikers and pedestrians will have no choice but to be forced into traffic to continue riding or to board the bus. Placard parking affects everybody,” he said.

A few other big, bold ideas that Ma says he’s on board with include bus lanes to LaGuardia Airport — not an AirTrain, just bus lanes — building world-class greenways up and down Manhattan and in each borough, and pedestrianizing Chinatown.

“People are against it until they see it,” he said.

Ma says for him personally, his bike has been an important part of his life, especially this past year — but it’s not his livelihood like it is for many, like the essential delivery workers who kept everyone fed when the city was nearly all but shutdown for months. The city needs better bike infrastructure not just for him, not just for recreational riders or commuters, but also for those who everyday keep the city alive and running.

“Since COVID, I don’t have to go to work and I don’t have to bike wherever I go, it’s not a necessity. I recognize for many people it is their lifeline — anyone should be able to bike in the city without feeling afraid for their lives,” he said.