Black History Matters: The Case for an Arturo Alfonso Schomburg Subway Station

As two candidates running for office who reflect the Afro-LatinX and Harlem communities respectively, we are coming together to advocate for a subway station to be named after Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. Black history exists as an ever-present reality, and honoring those who dedicate their lives to advancing Black history is incredibly important.

As our nation is rightly talking about the need to remove confederate statues, and odes to colonizers, we must also talk about lifting up our freedom fighters and those who paved the way, when it was popular. Connecting the Black and LatinX communities through research and love for the Black diaspora, opening the door and advancing the study of Black history, Arturo Schomburg is more than deserving of being recognized with an MTA station renaming in Harlem.

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg was born in 1874 in Puerto Rico. His mother was a Black midwife; his father was a first-generation Puerto Rican of German descent. Supposedly, when Schomburg was a child, he asked his teacher why they hadn’t learned about any Black history; she replied, “Oh, Black people don’t have any history.” Most biographies point to this as the inspiration for his life’s work.

In 1891, at 17 years old, Schomburg immigrated to New York. Although Schomburg had attended school in Puerto Rico, he lacked any official records, preventing him from continuing his education. Instead, Schomburg quickly became politically active, and in 1892 he founded Las Dos Antillas to advocate for Cuban and Puerto Rican independence. In 1898, when Spain ceded Puerto Rico to the United States as a result of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the independence movement largely disbanded. Schomburg’s interests turned to the African-American community. It was around this time that Schomburg began going by the English version of his name, Arthur. He didn’t abandon his Caribbean identity, however; his first major article, published in the Unique Advertiser in 1904, was a treatise on Haitian society called, “Is Hayti Decadent?”

Determined to unearth Black history and achievements, Schomburg began frequenting rare book stores and other collections, purchasing books, pamphlets, historical documents, poems, newspapers, speeches, letters, prints, art, and more. His collection grew quickly and covered a broad range of topics. White collectors had little interest in the materials he desired, allowing him to amass a staggering array of documents: original newspapers published by Frederick Douglass, collections of poems by Phillis Wheatley, letters from Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture, books and journals by Paul Cuffee, music by Chevalier de Saint-Georges, newspaper clippings about Ira Aldridge, and more. He also researched the lives of historical figures whitewashed by history, finding evidence of the African ancestry of naturalist John James Audubon, composer Ludwig van Beethoven, and Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, among others.

Schomburg’s knack for finding obscure documents and unearthing “lost” stories made him an indispensable resource for the Black writers and poets converging on Harlem. While continuing to work as a clerk and messenger during the day, first for a law firm and then for the Bankers Trust Company, Schomburg accumulated more material. In 1911, he co-founded the Negro Society for Historical Research with John Howard Bruce, and in 1912 co-edited that year’s edition of the Encyclopedia of the Colored Race. In 1914, he joined the American Negro Academy, of which he became president of in 1920, and in 1916, published the first bibliography of African-American poetry. In 1925, Schomburg published his most widely known essay, “The Negro Digs Up His Past” in a special issue of Survey Graphic.

In 1926, the Carnegie Corporation purchased Schomburg’s collection for $10,000 and donated it to the New York Public Library to be the cornerstone of the new Division of Negro History, Literature, and Prints (legend has it that Schomburg’s wife, Elizabeth, finally convinced him to sell—the collection had grown to take over their home). With the money from the sale, Schomburg traveled to Europe, visiting Spain, Germany, France, and England, finding new material for his collection, focusing on the African diaspora regardless of nationality. In 1931, Fisk University’s Library invited Schomburg to found and curate their Negro Collection, and in 1932, he returned to New York City to become a curator of the NYPL Division of Negro History, Literature, and Prints. As a curator, Schomburg continued to expand the collection, adding artwork both depicting Black subjects and by Black artists. These additions ranged from pieces by prominent Harlem Renaissance painters to French sculptures. He also traveled to Cuba, meeting with artists, writers, and scholars, and bringing back material for the library. Around this time, Schomburg also began to go by his given name again: Arturo.

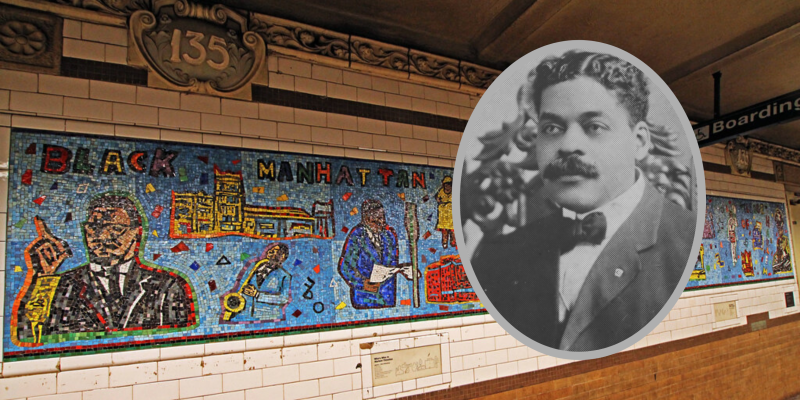

Schomburg died in 1938 in Brooklyn and is interred in Cypress Hills Cemetery. In 1940, the NYPL Division of Negro History was renamed the Schomburg Collection; in 1972, the 135th Street branch was renamed the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the current building opened in 1980. Schomburg’s legacy in the movement for justice and representation is unequivocal; while images of oppressors abound throughout our city and country, we cannot wait for the just recognition of those who paved the way for our current, and ever-growing movement.

This renaming would serve as a reminder towards the continuous and necessary work towards equity and justice; please sign our petition at www.KristinForHarlem.com/petition.

Wilfredo Florentino is a life-long Brooklynite and community advocate. He has served as a Brooklyn Community Board member since 2009; since 2014, as Transportation Committee Chairmn of CB5. Wilfredo is a candidate for New York City Council in the 42nd District in his East New York neighborhood, where he lives with his husband, daughters and dog. His website is at wilfredoflorentino.com.

Kristin Richardson Jordan is a poet, local activist, speaker, teacher, DSA member, Black queer woman, and third-generation Harlemite on a mission to disrupt District 9 (central Harlem) with radical love. Her political platform includes advocacy for police accountability, abolition, affordable housing, redistribution of resources, senior care, gun control, education, and environmental justice. Her website is at KristinForHarlem.com.