The Race for Public Advocate: Ten Candidates Address Street Safety, Transit

It’s a free-for-all for the most least important job in city government: Public Advocate!

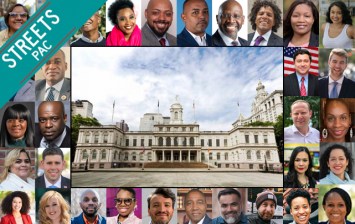

There are 17 candidates running to fill the seat vacated by new Attorney General Letitia James (remember her leadership in the job?). The New York Times has endorsed Council Member Jumaane Williams. The Daily News picked Council Member Eric Ulrich. StreetPAC tapped former Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito.

Still, it’s hard to tell the players without a scorecard, so today, Streetsblog provides one for Tuesday’s special election:

We asked the top candidates to discuss livable streets, safety and the future of transit — and while many answers overlap, subtle differences emerge on community board control of street redesigns, carveouts for (or expansions of!) congestion pricing, and what the public advocate should even be doing.

Here’s the only public advocate questionnaire you need, with answers from Michael Blake, Rafael Espinal, Ron Kim, Nomiki Konst, Melissa Mark-Viverito, Danny O’Donnell, Ydanis Rodriguez, Dawn Smalls, Jumaane Williams and Ben Yee (Ulrich declined to participate):

1. Thinking broadly, what is the public advocate job to you?

Done right, the position can and should help refocus the Mayor’s priorities on the issues that matter most to New Yorkers. But there are times when it should manifest as opposition — like the criminal handling and cover up of lead paint in NYCHA homes and the lack of transparency and accountability in the Amazon deal. These situations require an honest, informed and principled reckoning with the Mayor and his administration. Finally, the Public Advocate should use its seat on NYCERS to advocate for jobs, transportation options, and criminal justice reform, among other things. The Public Advocate can do more to support the power of the purse strings at NYCERS to create jobs and affordable housing.

Transportation is an area where the Public Advocate can take a citywide view, whereas individual councillors might be more focused on their own districts.

There’s also the ability to lead with bold ideas that are good for the whole city by introducing legislation and using the bully pulpit to unite coalitions of New Yorkers and push for positive change.

We know that the role of the public advocate should be to stand up for working families and everyday New Yorkers against the powerful and wealthy interests of our city.

I believe my vision fits perfectly into this broader agenda, and fully intend to use the role to push work towards stopping corporate welfare and putting money and resources back into working families and everyday New Yorkers.

I envision the Public Advocate to be New York’s lead activist and organizer of city residents. The next Public Advocate cannot advocate for the public behind closed doors. Public engagement will perhaps be the most important tool I will wield to not only communicate my efforts, but to implement and enact them. Drawing on my background as an activist, my instincts will naturally be to organize constituents and grassroots activists, turning the Public Advocate’s office into a civic engagement hub where New Yorkers can collaborate to hold all of city government accountable.

Additionally, I will make it a top priority to reform the Public Advocate’s office into a truly independent office. I will advocate for a charter revision to separate the power of the Public Advocate from politics — no longer in the line of succession to the mayor and barring any elected official from running for the office for five years — while also making the budget truly independent and expanded and calling for the DOI to be housed within the PA’s office, preventing political firings or appointments.

As Public Advocate, I will tell New Yorkers the truth about where our city falls short and fight for solutions to our problems, from our crumbling NYCHA system to the broken subway.

I have always used my voice to speak up and advocate for immigrants, for women, and for our LGBTQ communities — for renters, for subway riders, and for working families.

As Public Advocate, I will keep fighting for you.

I believe the Public Advocate must be independent of special interests, the mayor, and the governor, and unafraid to take on the institutional failings of our city government — sexual harassment, mismanagement (NYCHA), and corruption to name a few.

I am running for this position because I want to be Public Advocate, not because I want to be mayor or seek higher office.

The Public Advocate has the main charge to lift up the voices of New Yorkers, ensure their safety, fight for equity in all aspects, including transportation.

As Public Advocate, I will hold the Mayor, the Governor and the City Council accountable for what New York City residents deserve — a government that works and works to serve them.

As Public Advocate, I plan to open satellite offices staffed with Deputy Public Advocates in the boroughs with the highest number of CCRB complaints. This would give members of our community a more local place to go for help related to these precincts and to give CCRB office space outside of Manhattan to send staff to meet directly with community members in their borough.

I also believe some of the top issues that New York City must address include creating safe, affordable, income targeted housing, addressing major issues with NYCHA, improving transparency and accountability in government, fixing our broken MTA, reducing gun violence and overhauling our criminal justice system. Our city needs a public advocate who can effectively be an activist elected official, fighting for working families across the five boroughs.

Instead it has functioned as a taxpayer-funded campaign for the next mayor. I’m running on three programs that do three simple things our city government should have been doing all along to empower the people of New York:

1. Civics For All

Civic knowledge empowers people. I’ve seen it firsthand teaching civics to thousands of New Yorkers who go on to successfully make their communities heard. Civics For All brings that power to every corner of New York City with workshops, classes, online guides, and a “Political 311” hotline. This will allow New Yorkers to bridge the gap between those who have specific issues and those organizing to solve them. Be in person, online or over the phone, everyone has problems which they need civics to solve. The government owes people answers.

2. Power for Communities

We need to build leverage for bottom up, community driven city planning. Right now, City Hall forces communities to react to proposals it then speeds through approval. The Public Advocate should use its resources to bring together community institutions and stakeholders to develop a shared, proactive vision of how New York should develop. Then it should use its power to support plans which have buy-in from all communities in the city. Including holding hearings on agencies which disregard them and introducing legislation to enact their decisions. If our civic institutions – like Community Boards, Education Councils and local advocates – were united in a proactive vision of New York’s future, elected officials would have to reckon with their plan. No elected wants to upset every community at once; not a mayor and certainly not any Council Member who wants to be Mayor.

3. Justice for New Yorkers focuses the litigatory work of the office on systemic bad actors who corrupt our political systems and decision-making processes. The Public Advocate’s office has already done a great job calling out and suing bad landlords, but we have more bad actors in New York who need government oversight.

Justice for New Yorkers expands the focus of Public Advocate litigation to major threats like: employers who commit wage theft, a board of elections that illegally purges voters and a city that fails to enforce hard-won community concessions: like affordable housing , new schools, emergency centers, and public green spaces.

In the end, any candidate in this race must answer one key question: How can a new Public Advocate make this office relevant to solving problems and empowering communities so that city policy reflects the needs of residents?

2. What would be your top transportation policy agenda as public advocate?

By ending those rebates we could raise $11 billion a year – ten times as much as congestion pricing would raise. Fixing the subways and NYCHA housing would be the priority with that investment, and after that we could work on better public transportation in transit deserts and underserved parts of the city.

We need to push hard for adequate funding for our transit system, which we must dramatically improve to regain commuters’ confidence and trust.

We have to end the widespread practice of corporate tax giveaways and use that money to revamp our public transit system.

I support fully funding the MTA by taxing the wealthiest in our city, as well as the developers and corporations who have been incentivized to set up shop in NYC. I would not only push for full funding and a better tax structure, I would also push to expand the fair fares program and ultimately push towards elimination of fares for NYC residents, within 5 years.

If elected, I will use the bully pulpit to bring more attention to the crisis and advocate for real solutions. In addition to supporting congestion pricing, I have proposed Weed for Rails, a plan to generate badly needed revenue for MTA fixes through the legalization of marijuana. Paired with congestion pricing, Weed for Rails could fund fixes and make our trains and buses run better.

We must secure funding to fix the MTA.

I sponsored legislation in Albany to institute a Millionaire’s Tax, I would advocate for it in the City Council and in the legislature.

This will be achieved by holding the MTA accountable to complete much-needed maintenance and system update to improve reliable service; encouraging New Yorkers to choose walking or riding bikes over driving cars by improving street design and more protected bike lanes; reduce individual car ownership from 1.4 million to 1 million by 2030; and opening more streets to pedestrians with plazas and expanding initiatives such as Car Free Day.

The time for squabbling over responsibility is over. Using my experience fighting bureaucracy in the Obama Administration, I will work with all stakeholders who impact the MTA, be it the Governor and State Legislature in Albany or government agencies in DC. I will work with advocates to propose a new oversight system for the MTA that is transparent and accountable to New Yorkers, not subject to backroom deals among political insiders.

I would also prioritize more and better buses. To enable buses to move more quickly through the city, we should prioritize dedicated bus lanes (with enforcement!), transit priority signaling, all door boarding, and redesigned bus routes that reflect equity and fairness.

Jumaane Williams: Fixing #CuomosMTA.

Transportation is one of the most critical aspects of New York’s future and the most important thing a Public Advocate can do is ensure that the public is engaged in mapping out that plan. If undertake this task, we can dream bigger, build support for ambitious projects and do things more quickly having already addressed concerns and opposition that would arise in a piecemeal approach.

But, to answer with a specific policy proposal, it is critical that New York resolve the question of alternative transportation including bikes and e-vehicles. These modes of transit are the future of our roads. It is time to treat them that way and put as much effort into making them safe and ubiquitous as we have already done with cars.

3. Does the city build enough bike lanes? Does the city involve community boards too much or too little in that process?

We also need to enforce existing bike lanes better. When people park in bike lanes it forces people on bikes onto the footpath or into traffic, which is dangerous. I’d like to see the 311 app modified so people can report bike lane blockages.

Whenever dramatic changes are made to roads in an area, good or bad, it’s the residents in that area most directly affected. Community boards should have greater input for any significant lane changes during the decision-making or planning process, and not just as a center for complaints or concerns after a project is completed.

We must be much more aggressive about building more bike lanes, and the city should not allow its policy goals and public interest priorities in this regard to be vetoed by those who are intransigent and out of touch with what the majority of city residents want.

As a Council Member, I successfully brought protected bike lanes to East Harlem, and as Speaker, I passed Vision Zero to reduce traffic, pedestrian, and cyclist deaths.

As Public Advocate, I will continue to work to bring more bike lanes to New York City, expand access to bike share programs, and get more community members involved in the process.

The city needs to keep its promise when it comes to installing protected bike lines and installing bike lanes to reduce carbon emissions, improve mobility, and take pressure off of our transit system must continue to be a priority.

The local community and Community Boards must have a voice in the process, and I believe we must work together to ensure that our streets are safe for everyone.

Our community boards play an important part in voicing the concerns of New Yorkers. They must be a part of the conversation and educate community members on the benefits of protected bike lanes, and provide data and studies to support their stance.

The Australian tourist who was killed this summer is a tragic example of why we need protected bike lanes.

I do believe that community boards should be involved in the process. It’s important to have community input into planning decisions and getting their buy-in helps with the implementation.

The importance of linking these issues (and others) together is because while some communities welcome bike lanes, others don’t. As a result, there is massive pushback against expansion of the bike lane program and its continued expansion breeds increasing resentment; which is bad for the future of alternative transit. Community Boards and community stakeholders should be much more involved in the city’s planning process and be brought in as partners in a holistic visioning on how to address the challenges facing our city. Facilitating alternative forms of transportation like bike lanes and e-vehicles is good and critical policy; but sometimes that can only be appreciated through the lens of other issues which institutions like Community Boards generally view as their priorities.

This is exactly what the Power for Communities plan I’m proposing is designed to do. By bringing together stakeholders across communities to engage in sustained, proactive city planning, the Public Advocate’s office can both make the important case for alternative transit while building a consensus plan for rolling out more bike lanes and community friendly rules for e-vehicles. A program like this offers us the prospect of faster, more comprehensive rollout of alternative transit solutions because, once community buy-in is built, opposition and the necessity of ad hoc implementation will fall away.

In the end, how people engage with roads is matter of rules, education and norms. As dangerous as people say bicycles are, cars are significantly more dangerous. If we can figure out how to make 2 tons of steel moving at 25 miles an hour safe, we should be able to do it for 25 pounds of aluminum.

4. What has been Mayor de Blasio’s biggest mistake on transportation public policy, in your opinion?

There has been insufficient focus on infrastructure and signals and even less success implementing the Fair Fares program.

The mayor should have passed congestion pricing years ago.

With City Council support he still can, rather than wait for the State to do so.

The Mayor and Council have power under NY VTL Article 39, subsection 1642, which specifically allows the city to regulate and restrict traffic including by tolling and charging.

If he and the governor, who argue on everything, can work together to give away $3 billion without any transparency to Amazon, it shows they are prioritizing corporate interests instead of investment in people’s needs, even for something as vital to all of us as fixing the subways.

Deflecting blame and passing the buck on something so essential is not an acceptable substitute for leadership.

I believe his biggest mistake has been a lack of commitment to a broad, strategic vision to support non-automobile transportation in the city and reduce the impact of cars, indicated by his refusal to support congestion pricing and a failure to set truly ambitious goals for bike lane and bus lane buildout.

He has yet to support congestion pricing, which would generate millions in revenue to fix our broken transit system. He needs to start truly advocating for congestion pricing and make sure NYC gets the majority of the funds.

His unwillingness to support this measure shows that he isn’t taking our transit crisis seriously or listening to the needs of his constituents who rely on public transit to get around.

The Fair Fares rollout was an embarrassment.

Not only was the program late, but it only covered a fraction of the people included in the initial plan and applied to weekly and monthly cards. New Yorkers need leaders who will follow through on their promises, and this let many New Yorkers down.

Not supporting congestion pricing.

The mayor has solely relied changing on street design and more strongly enforcing traffic rules such as in the Congestion Action Plan, to ineffectively address the city’s severe ground transit issues.

I believe the biggest mistake de Blasio has made has been failing to take any responsibility for the MTA.

The mayor appoints four members to the MTA Board and could use his voice to advocate for reforms of the MTA governance board.

In the end, resource allocation questions are ones of political will. If you want to change allocations – like who gets to the use the street: moving cars, parked cars, bikes or pedestrians – you need buy-in from the public.

But, in terms of a policy decision, either a failure to crackdown on placard abuse or a failure to properly price parking/congestion in high traffic areas. Both of these make commuting on the street, by any means, significantly more difficult.

5. The public advocate must balance many constituencies. How would you prioritize street safety when communities sometimes oppose it?

If opposition stems from mere annoyance or being inconvenienced then in those cases it’s important make the case to the public that the safety of all take precedence over the exasperation of a few.

Despite broad public support, the issue of street safety too often lacks organized, vocal support and suffers from opposition from more organized, vocal elements who hold outsized sway on the city’s elected officials.

I believe the Public Advocate needs to serve as a counterweight by actively organizing on behalf of street safety and wielding the broad public support the issue truly has in the city.

Safety is the most important priority, and I have over a decade of experience balancing the needs of different constituencies. As Public Advocate, I will continue fighting for safer streets and access to public transportation and bike lanes. Millions of New Yorkers rely on our public transit and bike lanes to get to work every day, and they deserve to be brought to the decision-making table.

In the Assembly, I lowered NYC’s speed limit to 25 mph.

Some people were not happy about it, but I am proud to have played a role in making our streets safer for everyone.

You need conviction to fight for what you believe in and to be a good leader.

Changes to improve street safety affect people in any given community differently. It is the responsibility of the Public Advocate to listen to all sides, help the public access data used to analyze the issue and solutions, and make sure that the final decision is made for the safety of New Yorkers.

Manhattan is a city of pedestrians. Some people drive, some people take transit, some people ride bikes; but we are all pedestrians.

I would encourage communities to weigh the importance of saving lives against other concerns that they might have (such as free street parking for private vehicles).

6. Do you support congestion pricing — and, if so, in what form? Whose interests should be protected?

As for the details of congestion pricing, I think obviously we need to exempt emergency services vehicles and things like that, as well as people with disabilities. The system must be fair for delivery drivers, for example it could incentivize deliveries to happen outside of peak time. And we need to have high quality alternatives in place for people who drive into the city to make a living, like more park and ride facilities and better buses, trains, and ferries.

We should be using that money to fund the repairs and changes needed for our transit system, taking money from extractive multinational companies instead of our city’s residents. The interests of everyday New Yorkers should always be placed first — and in this situation that means both subway or bus riders and ordinary drivers.

Yes.

The city needs to move forward independent of Albany with its own congestion pricing system, using city tolls to fund the MTA. Funding and supporting mass transit must be our first priority.

The vast majority of people who work in New York City take public transit every day, and they are tired of being ignored. Congestion pricing will help middle class and poor New Yorkers who cannot afford to hop in a cab when the system breaks down.

As Public Advocate, I will continue fighting for working New Yorkers and make our city a better place to live and work for all.

I support congestion pricing, but I believe there needs to be protections for small businesses.

We also need to conduct an environmental impact statement to ensure that no community is burdened with more traffic.

I support congestion pricing on vehicles coming into Midtown. It has been proven successful in other cities similar to ours. It will improve the timeliness of MTA buses, generate funding for the MTA, make streets safer for cyclist and pedestrians, and help reduce our carbon emissions.

It would be a win for the city.

I believe congestion pricing should be in line with the FixNYC plan, but should go further: a surcharge on vehicles entering Manhattan south of 96th Street between 6 a.m. and 8 p.m.

In the event we go forward independently, I would support using the funds generated to support mass transit that is similarly 100% within the city’s control, like the NYC Ferry system.

Insofar as protected interests, properly implemented congestion pricing serves the interests of all New Yorkers by making the main business district easier to navigate and safer, while also creating revenues to invest in better and more accessible mass transit. That said, there are those who will be disproportionately affected by congestion pricing because our access to our mass transit system is inequitable. As a result, the additional revenues from congestion pricing should first go towards creating, improving and subsidizing mass transit in those areas. That means expanded bus service; investment in high-speed bus lanes and enforcement; and expansion and subsidization of express busses so that there are more options and fares are aligned with regular MTA prices. It’s ridiculous that express busses cost more than twice a regular bus and senior and student discounts don’t apply – it’s an effective tax on living far from Manhattan and incentivizes car ownership. Finally, the city should ensure that the Atlantic Ticket program moves beyond the pilot phase and is fully adopted.