Actually, If You Build It, They Will Bike

The emphasis of this year’s “State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods” report from NYU’s Furman Center is the housing market and foreclosure rates, but if you dig deep, you’ll find a table of Census data on citywide commute rates broken down by mode of transportation. While the authors make no comment on bike modeshare in their report, that hasn’t stopped several press outlets from distorting the cycling data and drawing erroneous conclusions from it.

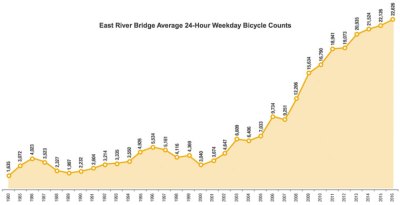

The Post, NY1, and DNAinfo all picked up the Census data point on citywide bike commute modeshare — 0.6 percent — and reached the conclusion that the city’s bike lanes aren’t attracting new cyclists. “If you build it, maybe they won’t come,” went the lede in the Post. The problem is, that’s a conclusion the Census data just doesn’t support.

Streetsblog has touched on the implications of Census data on NYC bike commuting a few times. Compared to DOT’s screenline count of cyclists entering the Manhattan central business district, the citywide Census data shows slower growth in cycling. But if you look at the Census data that reflects the same trips that DOT is counting, there’s a lot of overlap.

Broken down by borough, the Census shows that bike commute rates in Brooklyn have increased at about the same rate as the city’s screenline count, according to a 2010 report by Rutgers professor John Pucher [PDF]. The areas of the city with the highest bike commute rates are also the areas that have seen the greatest investment in separated bikeways and safer bridge approaches — northwest Brooklyn and lower Manhattan.

That makes the screenline a less-than-ideal proxy for citywide data, but it also means that the screenline is capturing the growth in cycling where the city has made the most robust improvements in bike infrastructure, as Pucher told Streetsblog last fall. “It does confirm that the state-of-the-art facilities in lower Manhattan and northwest Brooklyn, that they’re certainly well used,” he said at the time. “That’s a vindication of DOT’s policies.”

Comparing DOT’s screenline counts to the citywide Census data, as the Post and other outlets have been doing today, is sloppy because each method measures very different things. The screenline count is a good indicator for changes in biking to and from the CBD but doesn’t work as well for extrapolating citywide information about bike travel. The Census numbers are better for citywide trends, but not without flaws: The Census is widely thought to undercount immigrants, and the Census method won’t count you as a bike commuter if you do it, say, 100 times a year instead of 200. (You’ll only get counted as a cyclist if bike commuting is your “primary mode.”)

The Census numbers, while imperfect, do pose the question of why citywide rates aren’t keeping pace with cycling growth in the core of the city. In a paper released last month, Pucher notes that the recent expansion of New York’s bike network still leaves the city with the fewest bikeways per capita of the nine American cities his team studied — only one-eighth the ratio of Minneapolis, for instance. Pucher also calls out NYPD, saying that “the failure of New York’s police to protect bike lanes from blockage by motor vehicles has compromised cyclist safety.”

New York is a big place, and there are still huge swaths of the city where streets feel too dangerous for most people to ride. As we’ve seen this week, local politicians like Brooklyn’s Dom Recchia insist on keeping it that way. The lesson we should be drawing from the Census is that if we don’t build it, they won’t come.