Planners Tackle Big Questions About How to Shape NYC Development

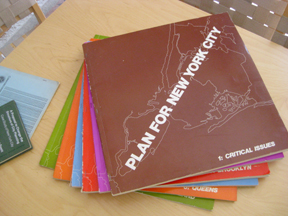

New York City’s unpassed 1969 comprehensive plan. Photo: Historic Districts Council

New York City’s unpassed 1969 comprehensive plan. Photo: Historic Districts CouncilThough the Charter Revision Commission looks likely to take a pass at reforming the city’s land use process this year, the door will remain open in the years to come to tackle the complex and controversial issues that surround planning and development in New York. The Municipal Art Society and Manhattan Community Board 1 held a conference yesterday to begin tackling some particularly thorny questions. The most difficult, perhaps, concern the roles of comprehensive planning and community-based planning in shaping the future of the city.

The lack of comprehensive planning is obvious if you look at the intersection of New York’s transportation policy and land use decisions. Take a project like The New Domino, where the city’s innovative Kent Avenue bike lane will run right alongside huge garages with 1,428 new parking spaces. The city’s right hand is helping people get around without cars while the left hand gives them more incentive to drive. What is really the goal for the Williamsburg waterfront?

At the same time, local communities routinely feel powerless to shape their own neighborhoods. Brooklyn Community Board 1 called for significant reductions in the amount of parking at the New Domino, for instance, but only received a minor cut.

In practice, these two approaches often conflict. Comprehensive planning can help set broader targets but tends to centralize decision-making. Community-based planning can create grassroots momentum for big changes like the transformation of Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza. But the political units assumed to speak for neighborhood residents — the city’s 59 community boards — often elevate parochial concerns that can thwart citywide goals, like creating safer streets and more sustainable development. (Most CBs are not as enlightened on parking policy as CB1.)

These are meaty issues, and ones worth thinking about. Here are some of the big questions and big ideas from yesterday’s conference:

- "New York doesn’t have a comprehensive plan," explained Sandy Hornick, the Deputy Executive Director for Strategic Planning at the Department of City Planning. "It’s unusual in that respect." Hornick explained that the city’s first attempt to write one, in 1940, ended with the resignation of the city’s first planning commissioner, Rex Tugwell, and that the second, in 1969, never was passed.

- Josiah Madar, a research fellow at NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, explained that he’s been researching where the Department of City Planning has rezoned the city. Properly evaluating that data, he argued, was impossible without a comprehensive plan. If most upzonings are near transit, but so are most contextual rezonings, "What do we compare that to in the absence of a comprehensive plan?" he asked. "Based on what do you tell people who want a contextual or a down zoning that, ‘No, they’re near transit?’"

- Pratt Center executive director Adam Friedman agreed that the city needs to "create a context for evaluating zoning changes," but called a comprehensive plan "too complicated and too inflexible for New York." Instead, he proposed a matrix of land-use goals, such as the total number of affordable units the city needs, against which zoning can be measured.

- The City Charter already requires a set of strategic plans by both the Department of City Planning and the Mayor’s Office, reminded Brian Cook, the director of land use and planning for Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer. Those plans, however, simply sit on a shelf and aren’t available online.

- Hornick argued that DCP already uses PlaNYC as a blueprint for its rezonings. "Eighty-seven percent of the permits in the last three years were within half a mile of transit," he argued. "I’m sure there’s no city anywhere else in the United States that comes close to that."

- Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer dismissed PlaNYC as inadequate, however. "Yes we have PlaNYC," he said. "But that is a mayoral component. It doesn’t have the breadth or the reach of long-term planning."

- "The shortcomings of PlaNYC is that it’s failed to tell us where we need to put these things," argued Real Estate Board of New York Senior Vice President for Research Michael Slattery. Housing one million new New Yorkers is an important goal to have set, said Slattery, but without more geographic guidance, it may not happen.

- "Denver is the newest and shiniest big city zoning code that might be worth taking a look at," said Armando Carbonell, the Chairman of the Department of Planning and Urban Form at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. After a long-term planning process called Blueprint Denver and five years of development, Denver implemented a contextual, form-based overhaul of its entire zoning code last month. Form-based codes can help create more walkable places by regulating the relationship of buildings to the public realm, rather than prescribing the bulk and use of buildings in a given area. Miami also passed a form-based rewrite of its entire zoning code last year. "Mayor Manny Diaz pretty much staked his career on this," said Carbonell.

- Carbonell cited some other models worth studying as well. Seattle offers density bonuses for providing a vast array of public amenities. "This is based on a recognition and an acceptance by residents that more density is an alternative to paving over the Cascades," he explained. San Francisco has invested heavily and successfully in figuring out exactly how much profit developers stand to make on a project, allowing the city to effectively negotiate for more concessions.

- David Kinsey, a New Jersey-based urban planner, highlighted the importance of comprehensive land use plans in most American cities. California and Oregon mandate that cities prepare comprehensive plans and keep them up to date. In New Jersey, he said "state law requires zoning to be substantially consistent with the master plan," giving the plan some teeth.

- Community boards "repeatedly express frustration that their role is merely advisory," said Hornick. "They’re advisory, but they’re not merely advisory." Local concerns frame the debate at the City Planning Commission and City Council, he argued, and when community boards or borough presidents vote against a project, City Planning approaches it with "heightened skepticism."

- "We have uneven results with the city’s land use review process," said Community Board 1 Chair Julie Menin. In one community, she said, neighborhoods win significant givebacks and in other communities, nothing. "The word uniform is really a misnomer."

- "Currently, the basic contours of a deal are struck before the certification," argued Friedman. By the time most community members have a chance to make their voice heard through the formal review process, he said, it’s usually too late.

- Eddie Bautista, the executive director of the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, decried the weakness of the existing 197a community-planning mechanism, which he said had been hollowed out by Department of City Planning rules. "The details are worked out by the agencies, and the agencies don’t want their hands tied," he claimed. "City Planning can sit on a community’s 197a plan," he explained, "and if you sit on a plan long enough, it gets stale."

- Slattery argued that residents have too much power currently. New York needs "a different kind of community board," he suggested, and "it needs to have more business representatives and more real estate representatives so that it isn’t only local voices."

- Hornick argued that community boards do themselves a disservice by preparing 197a plans in a vacuum. "People will spend years doing these things before talking to the government." That prevents coordination and cooperation with DCP.

- Responded Cook, "Rather than heightened skepticism, why not have heightened scrutiny?" He called for "No" votes at the local level to trigger supermajority requirement at the City Planning Commission.

- Friedman called for the city to negotiate with residents at the same time as it works with developers, not afterwards. "How do you make negotiations coincide, to make them meaningful?" he asked. "I think this is fundamentally a balance of power question."

- Stringer provided the conference with a history lesson on the community boards. "They were called community planning boards," he recalled. "That word was dropped in the 70s" as they became more responsible for service delivery. "Now with the success of 311 and the fact that we have all these professional service delivery agents," said Stringer, "community boards should go back to their original purpose." He called for providing community boards with the resources to employ professional planners.

- When asked about electing the City Planning Commission or community boards, Friedman replied that with New York’s democratic history, which once included a proportional representation system and allowed immigrants to vote for school boards, "I don’t think it’s so far-fetched." Bautista urged caution, however. "Think of the kinds of interests that would step to the fore if community boards were subject to elections," he warned.

- "Residents are not a special interest," said Friedman. "They can balance their natural desire to preserve their community with their excitement for the whole city and change." With tools, training, and actual responsibility, "they’ll rise to that challenge."

- "I have yet to meet what is an unreasonable community or an unreasonable industry," said Cook. "I’ve met plenty of unreasonable individuals and unreasonable businesses." He said that early and sustained engagement with the community elevates those who take planning seriously and diminishes those simply interested in yelling. With land-use training, he said, "people start speaking the same language."

- Slattery proposed a system in which communities make significant decisions but are constrained by a comprehensive plan. "The city would really make goals for housing growth and let the boroughs decide where to put it," he suggested.

- Slattery also said that leaving neighborhoods only a thumbs-up, thumbs-down decision on each project carries a big cost. "There’s got to be some carrots out there for communities to take," he explained.