Shaping the Next New York: The Promise of Bloomberg’s Rezonings

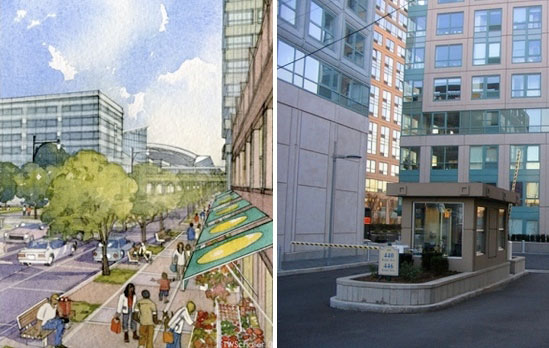

The Department of City Planning has mostly zoned for growth near transit, as in its plan for downtown Jamaica (left). Where the city has encouraged growth far from transit, however, car-oriented developments have followed, like Schaefer Landing in Williamsburg (right).

The Department of City Planning has mostly zoned for growth near transit, as in its plan for downtown Jamaica (left). Where the city has encouraged growth far from transit, however, car-oriented developments have followed, like Schaefer Landing in Williamsburg (right).This is the first installment in a three-part series on the reshaping of New York City and its consequences for sustainability and livable streets.

Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the Department of Transportation has built hundreds of miles of bike lanes and given acres of Times Square to pedestrians. Together with the MTA, the city is moving to construct a new rapid bus network for New York. But when it comes to livability and green transportation, perhaps the biggest legacy of the Bloomberg years will be something less tangible: Zoning.

Since taking office in 2002, Mayor Bloomberg and City Planning Commissioner Amanda Burden have rezoned one-fifth of New York City, approved countless special permits for developers, and assisted with financing for favored projects. Those decisions — the scope of which haven’t been seen since the total overhaul of NYC’s zoning code in 1961 — will shape the future of the city for generations. "The simple act of rezoning these areas," said Jonathan Bowles, director of the Center for an Urban Future, "has already or will spur

significant change in the landscape, the skyline, and the character of

these neighborhoods."

PlaNYC forecasts that one million new residents will call New York City home by 2030. Zoning determines where growth happens and where those new New Yorkers will live. It can focus development in dense, transit-rich parts of the city or in more

auto-dependent neighborhoods. And that in turn can spell the difference between a New York that increasingly favors transit, walking, and bicycling to get around, and a New York with more congestion, pollution,

and dangerous streets.

Grading purely on location, the Bloomberg/Burden rezonings are, by and large, a bright spot in

the administration’s record, though not without significant flaws and missed opportunities.

The

general thrust of the changes has been to funnel growth into relatively

transit-rich locations. Simon

McDonnell, a research fellow at NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, has conducted a detailed analysis of recent rezonings that examines proximity to transit. His research determined that, between 2003 and 2007, about three quarters of the lots rezoned for denser development were within a half-mile walk of rail transit stations. However, two thirds of downzoned lots — where density has been restricted — were also close to stations.

McDonnell’s research suggests that even while the Bloomberg

Administration has zoned for growth to be centered around transit, it

has also closed off the possibility of more intensive transit-oriented

development. The overall effect is positive, but it could be even

better. "It’s fair to say," McDonnell concluded, "that a majority of the net new

residential capacity that came online during this time period was near

rail transit."

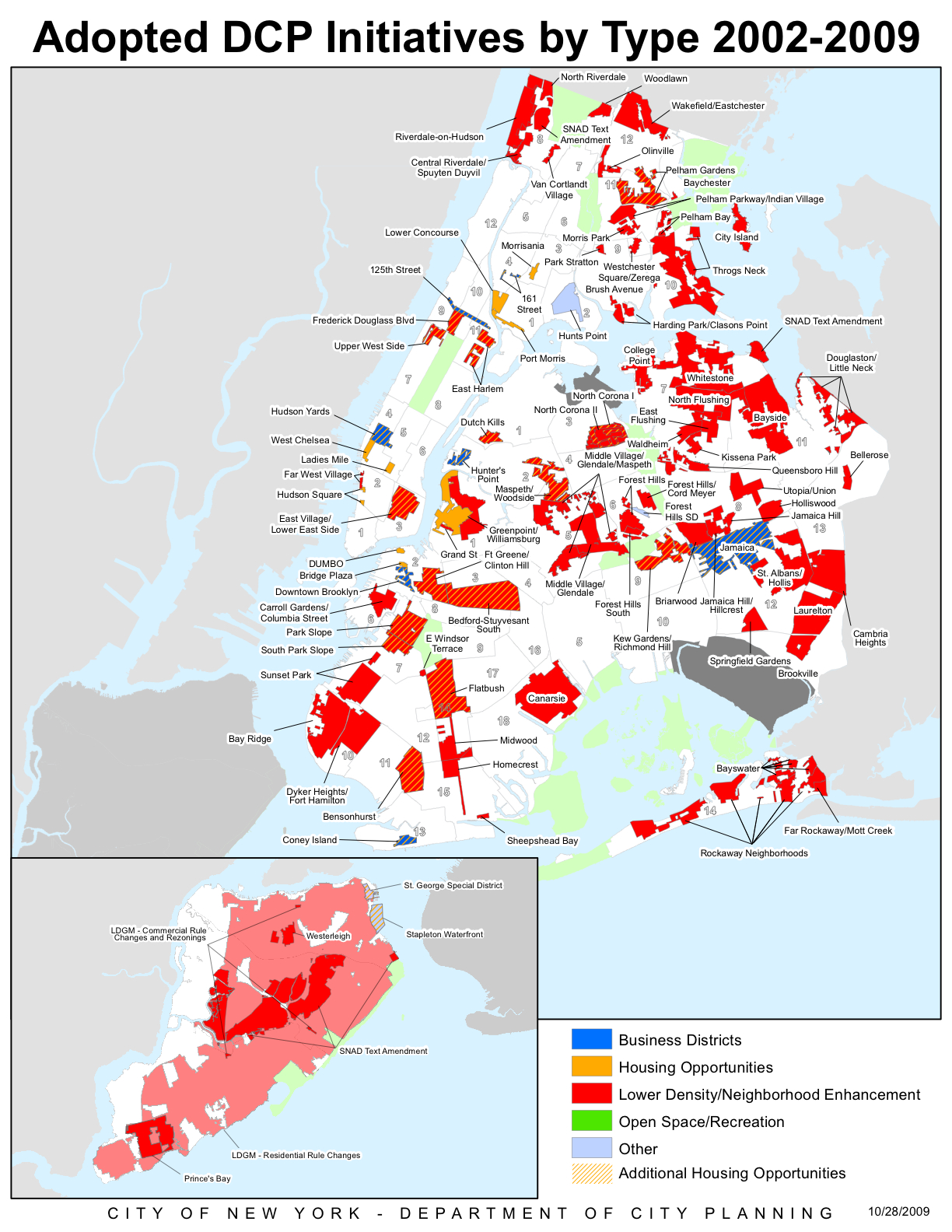

The Department of City Planning has rezoned 20 percent of the city under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Planning Commissioner Amanda Burden. Click for an interactive version of this map on the planning department site.

The Department of City Planning has rezoned 20 percent of the city under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Planning Commissioner Amanda Burden. Click for an interactive version of this map on the planning department site.The Department of City Planning cites prominent upzonings in transit rich areas like Downtown Brooklyn and the Bronx’s Lower Concourse as examples of its transit-oriented strategy. At the same time, in particularly car-dependent areas

like the Bayside neighborhood of northeastern Queens, the planning department has

ensured that major development will not occur.

Joan Byron, director

of the Sustainability and Environmental Justice Initiative at the Pratt Center for Community Development,

noted that "the political pressure to do these downzonings has often

come from self-protective, predominantly homeowner communities," but

that she still believes such downzonings promote sustainability.

The combination of zoning for density near transit and downzoning in car-dependent areas is a significant innovation, said L. Nicolas Ronderos, Director of Urban Development Programs at the Regional Plan Association.

In praising what he called a

"double approach," Ronderos argued that the planning department "sees transit-oriented

development not just through the lens of rail but also of automobiles.

It’s transit-oriented development not only as increasing density around

transit, but decreasing density where there is none."

While most upzonings have planned for growth close to transit, there are

important exceptions. Bowles pointed to the 2005 rezoning of Williamsburg and Greenpoint

as an example of particularly backwards transportation planning.

"There was a plan to create thousands of units of new housing on the

waterfront," he said, "many of which would come in a Greenpoint

neighborhood that had pretty deficient access to transit networks."

The typical rezoning is tough to classify as an attempt

to increase or decrease density across an entire neighborhood. Rather,

the general strategy at the planning department has been to increase density and

introduce a mix of uses along avenues and in areas next to

transit, while preserving the existing character of side streets and

more distant areas, often through downzoning.

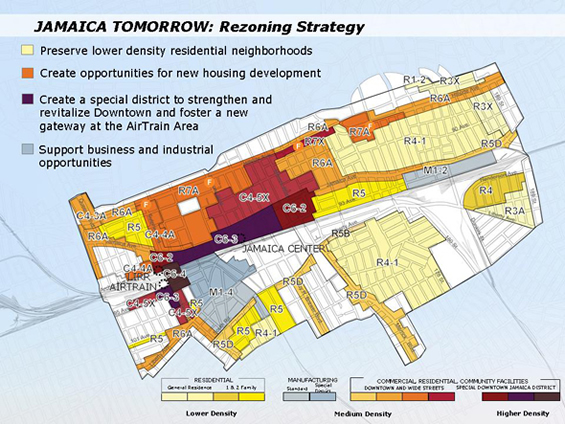

The rezoning in Jamaica channels growth along bigger streets and near transit. Image: NYC Dept. of City Planning.

The rezoning in Jamaica channels growth along bigger streets and near transit. Image: NYC Dept. of City Planning.Department spokesperson Rachaele Raynoff pointed to the

major rezoning in Jamaica as illustrative of this

approach. "Around the AirTrain, we zoned for growth," she said. "It’s a

tremendous opportunity with the confluence of subway lines and the

LIRR. And yet many of the low-density residential blocks further away

from transit were protected."

All told, the rezonings of the last eight years have laid the

ground for New York to build on its unique strengths as a transit-rich city. It’s a major accomplishment, but Bloomberg and Burden have more work ahead of them to fully deliver on the promise of a city that grows sustainably. As the next post in this series will show, zoning for growth near transit won’t necessarily translate into transit-oriented development or a walkable city.