Three Concrete Proposals for New York City Traffic Relief

This Morning’s Forum: Road Pricing Worked in London. Can It Work in New York?

Three specific proposals to reduce New York City’s ever-increasing traffic congestion emerged from a highly anticipated Manhattan Institute forum this morning. One seeks variable prices on cars driving in to central Manhattan, with express toll lanes and higher parking fees to keep things moving. Another seeks to get rid of tolls on less-congested bridges in car-friendly parts of town and replace them with congestion charging technology in gridlocked, transit-friendly sections of the city. A third plan relies entirely on enforcement of existing parking laws.

The forum, organized by the Manhattan Institute’s Center for Rethinking Development, opened with Partnership for New York City president Kathryn Wylde setting a collegial but urgent tone two days after releasing a report that put a $13 billion price tag on New York City’s traffic congestion. The Partnership’s analysis, she said, found that 48 percent of all motor vehicle traffic delay is "excess traffic congestion, beyond what we ought to put up with."

"Why do you think construction prices are going up one percent a month?" Wylde asked. It takes crews too long to get to job sites, and once they get there they spend valuable work time waiting for deliveries. "Manufacturing, an industry we have been hemorrhaging" is leaving New York City, in part, because of the difficulty in moving people, supplies and products, Wylde said. "A person who might go to a restaurant" in Manhattan will skip the trip if she’s staring at brake lights.

The problem Wylde says, is "How do you attack traffic without making commercial deliveries or taxis suffer?" London achieved a 15 percent "mode shift" moving approxmately 60,000 commuters from cars to other forms of transportation with its congestion charge. How can New York achieve similar results?

Bruce Schaller, who released a major new study on New York City traffic congestion this morning, presented the first and most detailed answer to that question. He proposed a combined system of congestion charges, highway express lanes and parking reform, emphasizing that the plan can’t just be about getting rid of cars or punishing motorists. It has to be about "making New York the kind of city that New Yorkers want."

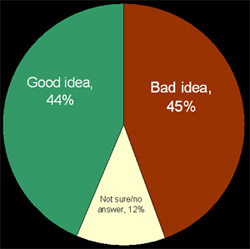

Schaller pointed to the results of a Tri-State Transportation Campaign survey showing that 44 percent of New Yorkers feel that congestion pricing is "a good idea" versus 45 percent against. It is worth noting that congestion charging starts with much higher approval ratings in New York City than it had in either London or Stockholm.

Schaller pointed to the results of a Tri-State Transportation Campaign survey showing that 44 percent of New Yorkers feel that congestion pricing is "a good idea" versus 45 percent against. It is worth noting that congestion charging starts with much higher approval ratings in New York City than it had in either London or Stockholm.

Schaller ran focus groups to test three ideas: London-style congestion charging, highway express lanes with tolls, and increased parking fees. He found that New Yorkers, in fact, are quite sophisticated in their thinking about the city’s traffic congestion problem and possible solutions.

Schaller found that there are six factors that drive public reaction to congestion pricing and other solution ideas:

1. Will reduce traffic congestion

2. Will solve my transportation problems

3. Enhances my transportation choices

4. Fair and equitable

5. Works as intended

6. Is supported and complemented by non-pricing policies

In other words, New York City’s auto dealership-supported tabloid media may not be accurately reflecting New Yorkers’ apparently intelligent and nuanced thinking on local transportation issues when it blares "Traffic Tax!" headlines and reports knee-jerk opposition to congestion charging and other traffic relief measures.

Schaller’s plan combines three elements: Selective road pricing, new highway express lanes, and more tightly managed and higher priced curbside parking.

Schaller’s traffic relief charges would apply to anyone crossing the Hudson River, East River or 60th Street boundary into Lower Manhattan. On weekday mornings he would charge $4 to any vehicle entering the zone between 6:30 and 10:00 am. During mid-day, from 10:00 am to 4:00 pm, all vehicles traveling in or out of the zone would pay $4. Then from 4 pm to 6:30 pm vehicles traveling out of the zone would pay the $4.

Schaller’s highway express lanes would be open to buses, vehicles carrying three or more passengers and any motorist willing to pay a fee. Times and fees would vary depending on congestion and also the State Department of Transportation’s identification of "feasible corridors."

Schaller’s highway express lanes would be open to buses, vehicles carrying three or more passengers and any motorist willing to pay a fee. Times and fees would vary depending on congestion and also the State Department of Transportation’s identification of "feasible corridors."

Schaller’s parking plan would apply to commercial districts and selected parking spaces. To show skeptics that usage fees can influence drivers’ behavior, he suggests setting up a pilot project to increase curbside parking rates with, perhaps, rates rising incrementally each hour a car occupies a spot.

To make these ideas politically palatable, Schaller added, all revenues generated by these new plans would need to be plowed back into public transport – especially in underserved areas like Staten Island, Eastern Queens and the Upper East Side.

Next up was transportation guru "Gridlock" Sam Schwartz, a former city transportation commissioner. Gridlock Sam immediately went to the root: "Our road pricing stinks." He lamented a regime in which "we toll people going from Queens to Queens or from Staten Island to anywhere" but let drivers "drive across the Queensboro Bridge" without paying tolls (and without funding upkeep on that bridge). His solution: Eliminate all tolls on bridges outside the central business district and impose charges "only where there is congestion and good public transit." This approach could work politically, he said, if it is demonstrably "revenue neutral."

Schwartz also argued that Brooklyn and Queens drivers would benefit from this approach. "People from Brooklyn and Queens would have five river crossings with no tolls. If you go over the Brooklyn Bridge, up the FDR and across the Willis Avenue Bridge, you didn’t set rubber in midtown Manhattan" and so you should pay no tolls, he reckoned. To make any traffic reform effective, Schwartz counseled, "we have to give Brooklyn and Queens a lot." And short of extending subway lines to Maspeth or Gerritsen Beach, the idea of a tight area for fees presumably leaves residents of those areas some latitude.

Councilmember David Weprin, who represents eastern Queens disagreed with Schaller and Schwartz. Since most people who live east of Kew Gardens or north of Forest Hills have to drive at least a mile to get to the subway, he noted, more frequent express bus service would have to complement any changes that made driving into Manhattan more expensive. He warned the audience to consider people who count on driving for their business and cited a statistic: "In London, 62 percent of businesses reported a drop in customers" after congestion charging. What Weprin didn’t say, however, is that the start of congestion charging in London coincided with a nationwide economic recession and a massive Tube construction project that shut down subway service in Central London.

The political gap between Weprin and Schaller seemed large, especially when a former Queens City Council member named Walter McCaffrey, now a lobbyist heading up a newly formed group called the Coalition to Keep New York City Congestion Tax Free, rose from the audience to declare: "A tax is a tax is a tax." But there may be more room for compromise than such rhetoric might suggest. Council member John Liu, who represents Flushing and chairs the Transportation Committee, told me that he would like to see more express bus service in his district. "Nobody wants to pay new charges for anything," he said. "But if, in return, they get something like more express buses." He left the forum at about 9:50 to conduct a hearing at City Hall on express bus service.

So wheels are in motion. Mayor Bloomberg will deliver a major speech within a week outlining his sustainability plan for the city, and advisers say traffic congestion issues will be front and center. Stephen Hammer of Columbia University challenged the panel to push the New York City metro region into a broader conversation about encouraging walking, bicycling and living near mass transit. Road pricing, clearly, is just one cog in the machinery New Yorkers will have to build to make the city livable.