New Report on Roads Uses Old Assumptions

A new report on the costs of aging roads [PDF] has gotten a lot of attention over the past week, with both Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood and the Washington Post touting its conclusion on the danger of "deficient roadways."

On its face, the report sounds like an argument for prioritizing road repair and modernization over new construction, which is certain to be a flashpoint as Congress works on a new federal transportation bill. But some of the upgrades that the authors suggest rely on outmoded assumptions about driver safety — not to mention pedestrian safety, a concept never mentioned in the report.

Here’s an excerpt:

Numerous solutions — some simple, some complex — could help make the roadway environment safer for users. These improvements include structural changes such as adding or widening shoulders, improving roadway alignment, replacing or widening narrow bridges, reducing pavement edges or drop-offs, and providing more clear space in the area adjacent to roadways.

Adding or widening shoulders for bike lanes or pedestrian paths is one thing, but the notion that driving can be made safer by widening and straightening roads (or "improving roadway alignment," as the report puts it) has been debunked by "Traffic" author Tom Vanderbilt, transportation planner Eric Dumbaugh, and others. In fact, making roads more complex and curvy can often serve as a deterrent to unsafe driving practices, particularly on urban streets.

But the report, commissioned by the Transportation Construction Coalition (TCC), seems to have concluded that urban areas don’t need to be considered separately from interstates.

"Although this study did not break out costs by class of roads, interstate highways are built to higher safety standards than other roads," the authors state — as if a new four-lane freeway through Chicago or Brooklyn would be a reasonable safety-enhancement move.

Roger Henderson, an engineer at Henderson Consulting in North Carolina, said the report made a solid attempt to link transportation and public health but made "a critical mistake" in treating all roads in the same way.

The report seems to argue, Henderson said in an interview, that "federal money should be

spent to cut down trees and move poles away from the roadway. I agree completely when

it comes to interstates, but this is the wrong study to make conclusions in any urban setting."

The report’s sponsorship may have had an effect on its conclusions, Henderson added.

Indeed, the TCC is an alliance of unions and trade groups that — as as the Post succinctly put it — "has a vested interest in funding for road

construction."

Taking its origins and questionable assumptions into account, however, two maps in the report tell an interesting tale of the regional toll exacted by traffic.

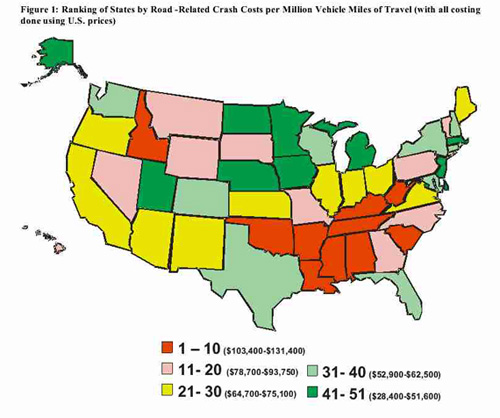

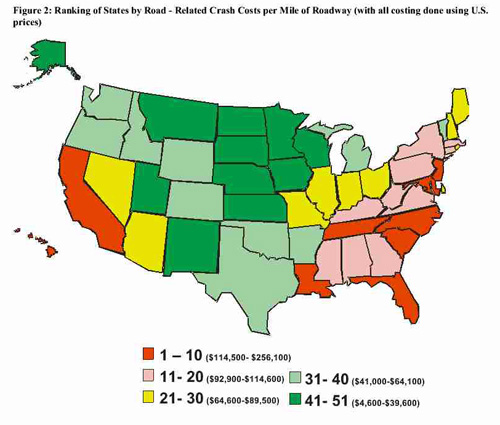

The map above depicts road-related crash costs for every million vehicle miles traveled on state roads, and the map below depicts road-related crash costs for every existing mile of roadway.

The southeastern states of Louisiana, South Carolina, and Tennessee rank in the top 10 on both maps, earning them the status of "worst road-related crash problems," according to the TCC study.

By contrast, California and most of the northeast corridor rank high in crash costs per roadway mile (see below) and much lower in costs per million VMT (see above). The study’s authors, who hail from the Pacific Institute of Research and Evaluation, attribute the trend to "traffic density" — making a powerful argument for giving special attention to expanding transit options, including high-speed rail, in California and the northeast.

Put simply, the problem in those areas isn’t a shortage of road miles; it’s a surplus of demand for the movement of people and goods. If anything can be gleaned from the TCC report, it’s the importance of imposing a "fix-it-first" requirement for highways nationwide.

Still, without an alternative to driving in highly developed areas, simply repairing roads isn’t enough.