T is for Transit-Oriented Development

Planning a city around transit doesn’t mean you have to cluster everything inside the core business district. Copenhagen, whose thoughtful bike network we’ve explored elsewhere, recently commissioned Chelsea-based architect Steven Holl to design T-Husene, a place for living and working outside the core city. The architect’s renderings, released November 2, fit into a town that fits into a local rail line and a regional rail network extending as far as Sweden.

It’s an inspiring blend of striking architecture and compact planning. Imagine: roughly 54,000 square feet of apartments on top of 37,500 square feet of retail, with a large allotment of open space. Holl’s design shows how tall structures, plenty of natural light and strategic use of grass can deliver a sense of exploration without sprawl. Says Holl: "It is a sharp contrast to the American urban sprawl which is characterised by highways and endless seas of houses."

It also takes the wind out of the argument that only car-centric urban design can satisfy a yearning for individual expression. This is no Soviet-style block. Again, the architect: "We wanted to create a sense of autonomy, individuation, and particularity for each apartment and tower. One of the failures of modern housing comes from the lack of individualization." Ditto for one of the failures of modern sprawl.

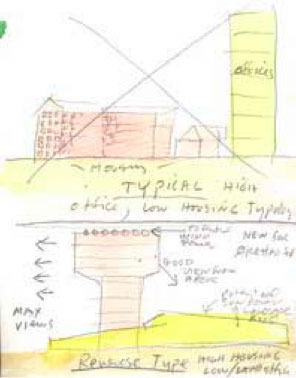

Here are some images:

The Copenhagen government chose a strategic site for the project. It sits on a site with a ten-minute rail link to downtown Copenhagen and a direct rail connection to Malmo, a Swedish city. It’s tempting to imagine such lovely forms in the South Bronx, eastern Queens or even New Jersey, with links to airports and office-park suburbs, but it’s hard to move this image beyond fantasy until the city gets serious about concentrating new development near transit hubs in under-built areas.

That won’t be easy. The MTA controls most of the transit infrastructure and other entities own most of the land. But there’s a new team in Albany and a new drumbeat for walkable neighborhoods inside and around New York City. Such developments can’t be generic. But as these images show, they can be intriguing — and beautiful.

No one is advocated for pedestrian-only malls, and to conflate that with classic urbanism is mistaken.

Greg: My bad, and thanks for the chance to clarify. You’re right that "troublesome" is a weasely word, and the connection between a canned ped-mall and a true urban fabric is flimsy. But imposing a 19th-Century aesthetic doesn’t always equate to delivering a vibrant or varied public realm. Consider the LoDo section of Denver, a grid of converted factories with lofts upstairs and boutiques and bars below. You’ve got a ballpark at the basin and ample sidewalks, but the buildings squat on corners and fail to provide windows or plazas that would take in the sweeping Rocky Mountain views. It feels like a movie set. This may be an area where the landscape and cultural traditions lend themselves to lower density and longer ramblings- and where progressives should seek fuel-efficient cars or exciting public transit rather than advocating for tight sidewalk grids. Vincent Scully, the architectural historian who influenced 20th Century ideas about urbanism, loved the New England town but equally loved the Anasazi villages. He wouldn’t have said their broad boulevards or temples mimicking the nearby mountains were "anti-people," and neither would we. There are as many keys to unlocking public comity as there are forms of public community. All I ask is that we give each honest effort a chance.

Sure, Alec, let’s give three-legged pants an honest chance.

Even though we can be pretty certain that they will not be functional for human bodies walking around in the world, three-legged pants would be an exciting theoretical leap, a break from the confining strictures of tradition, and an aesthetic breakthrough. Alec: What, specifically, are you advocating?

I’ve read your article and your entire line of defensive comments (I really don’t think anyone is attacking you personally here — they are challenging your idea that this development looks good), and I genuinely don’t understand what you are pushing for here. Can you explain it clearly and concisely?

Thanks. I’m advocating thinking carefully about context and culture before we start tossing around terms like "crap" and declaring ourselves more qualified to commission projects than clients who live and govern there.

Alec, I would argue that we can’t “give each honest effort a chance.” For a number of reasons. The first one is that we’ve been doing this for 60 years and it’s been an unmitigated disaster for our built environment. Second, it’s hard to look at this or others like it as an “honest effort” when architects are so unwilling to learn from past mistakes, in pursuit of other agendas entirely. Mistakes that are now so glaringly evident.

The quibbles you have with LoDo are pretty minor issues, window placement and so forth, not fundamental flaws in the design philosophy. Overall, it’s a successful urban space that people have responded to enthusiastically. We have precious few of these nowadays. And if it does look like a movie set now (a point I’m not sure I’m willing to concede) it probably won’t in 15 years, and it definitely won’t in 30.

I am taking my own advice and listening to you all. I don’t think it’s fair to condemn this project and I think its looks are inevitably a subjective matter, but I’m grateful for the debate about the difference between architecture and planning. And for the passion you bring to it. That passion, whatever plan it propels, makes cities durable.

Also, I think that “thinking carefully about context and culture” is exactly what we’ve been doing in criticizing this development. As far as who is “qualified” to dislike and critique an urban development, this is a obnoxious argument that architects fall back on when they have nothing else to counter with.

I’m sure there are plenty of locals, if not most, who will not like this development and feel the way we many of us on the blog do. Claiming some kind of cultural legitimacy for the project based on whatever developer or government official initiated it seems disingenuous to me. I wouldn’t be surprised if Holl spent a lot of time in Chelsea working out an elaborate, abstract theory of how these buildings will relate to and reflect Swedish culture (and he’s happy to spend three hours trying to explain it), but I’m willing to bet the average Swede is going to see the same towers in the park that we do.

It occurs to me that this conversation and critique could be constructively directed at Atlantic Yard’s “concept-drive”, “towers-in-the-park” design masquerading as TOD, and that this, now very well developed critique, may actually be one of the most effective ways to counter it at this juncture.

Some of these same critiques are being made, but are getting lost for AY by the same weak defenses. In both cases, despite what the counter arguments seem to be defensive of, we are not focusing criticism on issues with towers, density, creativity, “good design†or new development.

AY has not been sufficiently accused of being towers-in-the-park, because they do appear to meet the street and offer neighborhood oriented space in many of the renderings, but if you look at the footprints and compare it to the Gowanus housing project (as MAS has) they are not very different.

If someone can think of a positive example of towers-in-the-park, what are they?

Whether it is nice to live in, or even nice to look at, is not the issue.

Interesting comments from all of you…my opinion is that we lost knowledge of how to design people places and fully understand what good urban design is about. Modernist experimentation in last 80 years brought valuable ideas, but generally, we failed to build beautiful cities for people. I blame vastly Academia for brainwashing unsuspected youngsters with their disconnected-from-reality ideologies. There are timeless principles how to make good urban design, no matter if it is expressed in classic, neo-traditional or contemporary design language. The problem is that majority of planners and architects today do not understand fundamental principles of it. Everybody is searching for latest weirdest form to distinct themselves from the rest of the crowd. It’s fine to have landmark, iconic archiutecture, but that one represents less than 10% of any city. What about 90% of average stuff happening? Young guys are doing their flashy photoshoped imagery without substance behind it. Steven Holl is one of myriad of “starchitects” supported by fashionable magazines. He brings interesting ideas in architecture, but if you really know his opus, you would notice that most of his urban buildings are “autistic”, do not communicate at all with surrounding environment, they are self-indulgent, immersed in their own world of symbols and abstraction and do not contribute to the whole (city).

This project is not an exception – just another ego-trip of the developer and his architect.

I just came across this debate. As an architect, I continue to be amazed by the ability of my profession to keep coming up with new fads ….remember Brutalism? Post-modernism?… Someone wrote that Frank Gehry said that “he doesn’t do context”. Well, he and a few others started this new fad of formalistic, anti-human places that is sweeping the world. Even in Vietnam, according to today’s Times. By the time these projects are built and shown to be inherently dysfunctional, the profession will be onto something else “new”, god help us all. Call me sentimental, but just give a nice coffee shop on the corner with a view of a busy street.

Steve

Hate to break it to you, but the towers in a park did work. Think Co-op City and Stuyvesant Town. Subsidized, poorly built, towers in the park that bulldozed fragile neighboorhoods and all the jobs in them were the real enemy. I don’t think poor people could afford to live in a Steven Holl Tower. The retail is in the base of the building and the transit would be a short walk away. It would work, but yes – you would have to sacrifice the well-defined public space of the street. Sipping coffee watching people go by isn’t an activity for everyone, strange as it may seem.