Environmental Justice Advocates Seek to Regulate ‘Last-Mile’ Trucking Facilities

The city’s outdated zoning code must be amended to give regulators the teeth they need to rein in “last-mile” distribution facilities that are popping up in low-income communities of color, environmental justice groups said as they filed a zoning proposal on Wednesday night.

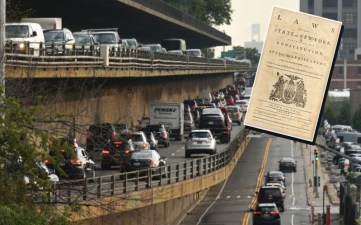

Local pols, community members, and advocates have long been sounding the alarm over the proliferation of last-mile facilities like Amazon, FedEx, and UPS — where large trucks drop off goods for sorting and loading onto other trucks or cars for distribution — that are setting up shop in neighborhoods like Red Hook, Sunset Park, Hunts Point, Maspeth, Williamsburg, and Bushwick that now bear the brunt of emissions and reduced street safety.

But thanks to current zoning dating back to 1961, the city has no say over where or how many warehouses are built — beyond a requirement that the facility is built in a manufacturing district or C8 commercial district, which are typically in low-income communities of color where land is cheaper. As a result, such warehouses are clustered in a few increasingly put-upon neighborhoods.

“[We need] a special permit process for these last-mile facilities that would basically allow the city to address the emissions and other environmental disparities that are occurring because of the increase in truck traffic and emissions in these neighborhoods,” said Kevin Garcia, a transportation planner at NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, which is part of the so-called Last Mile Coalition that submitted its zoning proposal to the Department of City Planning. The coalition includes UPROSE, El Puente, Red Hook Initiative and The Point, and Council Member Alexa Aviles and Assembly Member Marcela Mitaynes, both of Sunset Park.

“There’s a lot more vehicles, whether it’s delivery vans or trucks, they’re on on the roads, they are double-parking, triple-parking, they’re increasing emissions, but a lot of these facilities are found in communities of color or next to low-income communities, so they are spewing out a lot of not just carbon emissions but other vehicle pollutants,” Garcia added.

The special permit would set forth the following conditions:

- Any last-mile warehouse must be at least 1,000 feet from any school, park, nursing home, or public housing development.

- Last-mile warehouses must be at least 1,000 feet from another such facility.

The city’s “significant maritime and industrial areas” are attracting many last-mile facilities, though not using the maritime part. - Last-mile warehouse located in what’s called a Significant Maritime Industrial Area, which are designated waterfront areas, must conduct 80 percent of deliveries by marine transportation (see map).

“We don’t want to kill the last-mile trucking warehouses, we don’t want to kill the industry, what we really want is a public review process and we want to make sure that these facilities are good neighbors,” said Garcia.

In addition to encouraging use of the city’s vast waterways and rail systems, the amendment would also incentivize deliveries made on foot and on two wheels, to counter the massive number made by truck and van, according to Garcia.

Before Covid-19, roughly about 1.5 million packages were being delivered daily in the city. But as with most things, the pandemic changed the way people live, and the number of packages delivered daily across the boroughs jumped to about 2.4 million, advocates and experts say.

Now, the trucking industry delivers nearly 90 percent of the city’s goods on 120,000-plus trucks daily. And without any mitigation measures, experts estimate that number could increase again by 67 percent by 2045, bringing a whopping 75,000 more trucks everyday to city streets.

The city can’t let that happen, advocates warn, and the fact that the warehouses are being constructed as-of-right is no excuse. If the zoning change is ultimately approved by City Planning, any newly proposed facility would be subject to the city’s full land-use review procedure known as ULURP.

“If you’re going to build this facility, how is the facility going to use e-cargo bikes? Are they going to have charging infrastructure at the site…so looking at electric vehicles, looking at how to bring goods via rail, and how to bring in goods, but also deliver goods by bike, or walking,” Garcia said. “We want to reduce the number of cars and trucks that are leaving the facility as well.”

Still, the special permit will only apply to future warehouses, not those currently in operation. But a little-known piece of legislation introduced this year, known as indirect source rule, similarly seeks to crack down on last-mile facilities statewide by requiring the Department of Environmental Conservation to “conduct a study regarding zero emissions zones,” according to Alok Disa, a senior research and policy analyst at Earthjustice.

Advocates rallied in December to demand the city regulate the warehouses, and locals for years have been begging the Department of Transportation to at the very least study the damage they’re causing.

“DOT has its hands raised a little, saying, ‘We don’t have jurisdiction here because it’s as-of-right.’ Without changing the zoning there’s no hook for other city agencies to do anything…the community had no say, no seat at the table,” he said. “A special permit will create government action.”

A City Planning spokesperson told Streetsblog that the agency is reviewing the proposal, which “raises complex transportation, land use, and legal issues.” Amazon declined to comment. FedEx and UPS did not respond.