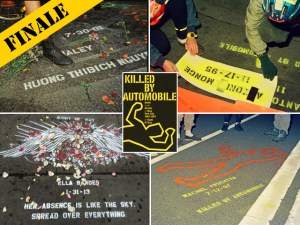

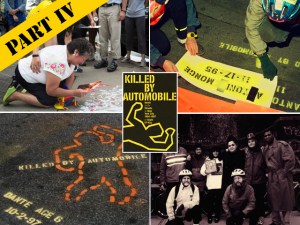

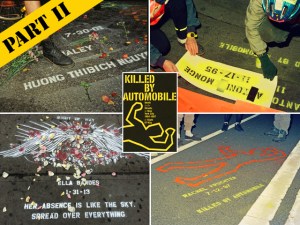

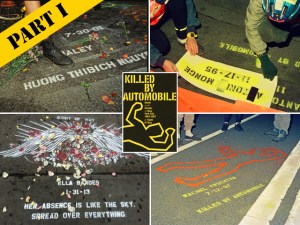

History of a Movement, Part V: Things Fall Apart

Amid the bloodiest year in Mayor de Blasio’s Vision Zero, Streetsblog continues its seven-part series focusing on a key strand in the movement for livable safe streets, written by a central figure in that movement, Charles Komanoff. A former head of Transportation Alternatives, Komanoff 25 years ago launched a highly effective public awareness campaign calling out the daily carnage on New York City streets. Under the name “Right Of Way,” his group brought the brutal reality of pedestrian and cyclist deaths to the public eye in the form of high-visibility street actions (including one arrest). Part I last Monday opened with the first “Killed by Automobile” stenciling in December 1996. Part II last Wednesday focused on how the movement began to generate press coverage. Part III on Friday looked at how the movement branched out. And Part IV on Monday looked at the publication of the book, “Killed by Automobile.”

The year 1999 should have been a time of triumph for Right Of Way. While we were finalizing our groundbreaking Killed By Automobile report (see Part IV), new data was pointing to a substantial drop in pedestrian fatalities in 1998. Maybe our stenciling exertions were entering broader consciousness and changing drivers’ behavior. We would apply for a state safety grant to pinpoint which kinds of motorist recklessness were decreasing the most. We hoped to take our advocacy nationwide as well, much as Jon Orcutt and I had done a decade earlier as spearheads of a militant yet optimistic new wave of urban cycling advocacy at Transportation Alternatives.

Instead, reality — and the system — fought back, beginning with our first (and only) bust, outside the Queens criminal court building on a weekday morning in late January.

We were painting a memorial stencil for Aaron Brown, a 9-year-old run over two days after Christmas by a 19-year-old who was racing from a fender-bender. Queens District Attorney Richard Brown hadn’t pressed charges, and his staff was rebuffing our calls. Stirred by our brand-new bond with the family of Dante Curry (see Part III), rather than stenciling where Aaron was killed we would bring the action to Brown’s doorstep.

In retrospect, this decision seems … unwise, shall we say. We were quite unprepared for the inevitable NYPD presence at the Queens citadel of justice, which swooped down on us as we were photographing our handiwork. I took the rap and spent 28 hours in the system, alone, most of it in a tiny, cramped holding cell. It was miserable and dispiriting.

Afterwards, we considered contesting my misdemeanor obstructing governmental operation charge on free speech grounds and turning my trial into a Chicago-7-style teach-in about traffic violence. But a trial would unfold in sleepy, faraway Kew Gardens rather than media-friendly Foley Square. Right Of Way couldn’t afford a defense attorney, and we were rushing to wrap Killed By Automobile before spring.

We were running on fumes. Right Of Way’s workload suddenly felt immense — stenciling, database management, crash analysis, writing Killed By Automobile — and we hadn’t built an organizational structure to handle it. Something had to give. I took a plea: adjournment in contemplation of dismissal, no illegal activity (i.e., stenciling) for six months, and a $500 fine which the group and I split.

The Times’s supportive coverage of Killed By Automobile gave us a lift, and so did our concurrent “street memorial day,” when eight teams of stencilers fanned out across four boroughs and painted 80 memorials. Our next endeavor, we hoped, would be a commission from the governor’s traffic safety committee — each state has one, funded by federal grants — to apply our crash-causality methodology to elucidate the 20-percent decrease in 1998 pedestrian fatalities.

Our grant, we made clear, was intended to transmute that good news into safer-streets policies across the city and state. To no avail. Then-Mayor Giuliani’s DOT falsely told the safety committee that it had a study in the works, dooming our idea. There would be no study. Whatever brought about the sharpest drop in pedestrian deaths on record would remain a mystery. And Right of Way would remain unfunded.

As it happened, we were summoned for one more analysis, a sequel of sorts to Killed By Automobile, but addressing cycling fatalities only. “The Only Good Cyclist” was prompted by the revelation in late December 1999 that 35 cyclists died that year in collisions with cars and trucks — a fact that the NYPD concealed even as the bodies piled up, and then blamed on cyclist recklessness.

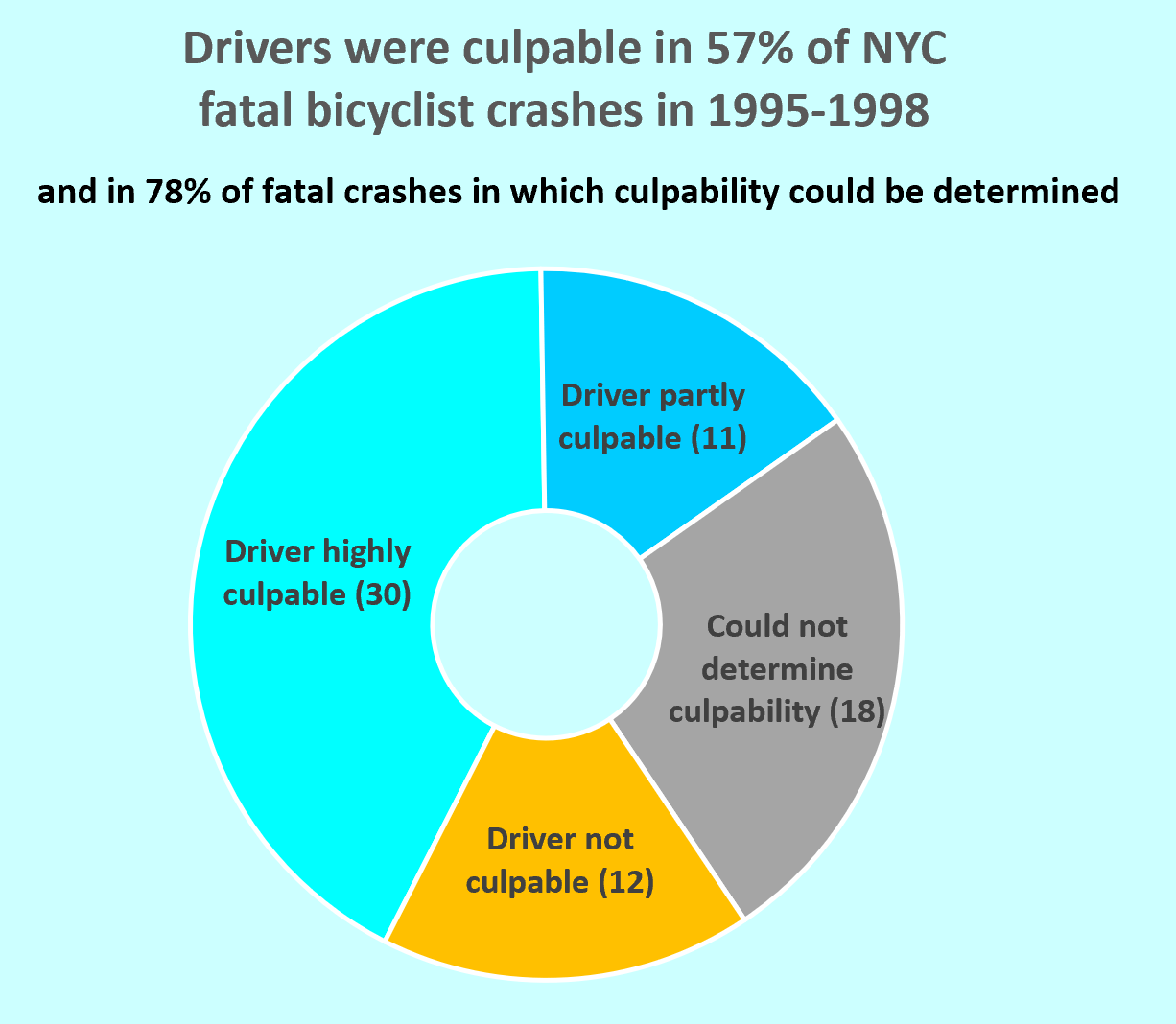

“Good Cyclist” co-authored with Michael Smith and issued in May 2000, examined 71 fatal bike-vehicle crashes from 1995-98 (1999 crash reports weren’t available) through the same culpability lens we applied in Killed By Automobile. As in that report, we found that drivers were at least partly culpable in most crashes that killed cyclists, despite the fact that even when drivers were cited for DUI or unlicensed operation — 10 cases in all — we didn’t automatically blame the driver but instead classified those cases according to the particulars reported for each crash. As we noted in our report, “We are more lenient to drivers than is the law.”

“Good Cyclist” conclusively refuted police officials’ repeated claim that bicyclists, not drivers, are responsible for most deaths. The report landed with a thud, however, dismissed not only by the NYPD but by a media and culture that declined to distinguish defensive infractions by cyclists, such as slipping through red lights when no cars were approaching, from dangerous and consequential recklessness by drivers.

Our other report that year, The Price of a Ticket, may have been too far ahead of its time. In it, we quantified the collateral damage of racial profiling by New Jersey State Police in terms of highway deaths: that by misplacing police attention from dangerous driving onto racially motivated harassment of minority drivers, racial profiling made New Jersey’s highways less safe than they would have been if the police had concentrated their efforts on dangerous driving without respect to skin color. No media picked it up.

With occasional exceptions when grieving family or friends reached out to us — a bicycle rider killed in Tribeca in 2001, children run over in Queens in 2003, teen cyclist Andre Anderson killed in Far Rockaway in 2005 — RoW’s stenciling largely ceased for more than a decade.

Beginning in 2005, cycling fatalities — nearly 200 and counting — would be memorialized as Ghost Bikes. But post-9/11 New York City, awash in Twin Towers mourning and Iraq War triumphalism, had no project marking pedestrian deaths. This would change in 2013, when new energy took root in Right Of Way and gave birth to a more welcoming and inclusive form of memorial stenciling.

Watch for Part VI on Friday.