THE DE BLASIO LEGACY: Eight Years Of Broken Bus Policy

Mayor de Blasio failed bus riders.

The mayor who entered office in 2014 promising a “world class” Bus Rapid Transit Network is leaving the vast majority of bus routes in worse condition. Shortly after de Blasio took over, overall weekday bus speeds were 8.2 miles per hour citywide, according to the MTA’s bus dashboard, which begins in January, 2015, and as of November 2021, those buses are running at an average of just 8 miles per hour.

Even a small numerical drop adds up to tens of thousands of lost hours for working people — and it’s the wrong direction for a mayor who promised in 2019 to speed up buses by 25 percent by the end of 2020 and also promised a citywide 10-mile-per-hour average. Buses didn’t even manage such speedy service during the pandemic, when citywide speeds rose to 9.2 miles per hour because of largely traffic-free streets.

Even on Select Bus Routes, the city has failed to ensure that buses indeed get the “select” treatment. In January 2015, such buses averaged 9.8 miles per hour on their routes. By November 2021, the speed had dropped to 9 miles per hour — a drop of more than 8 percent.

Pick almost any bus route in the city, and the failure of the de Blasio administration to improve the lives of bus riders is laid bare:

- The B67 in Downtown Brooklyn and Park Slope: Weekday bus speed was 6.4 miles per hour in January 2018 and dropped to 6.3 by October, 2021.

- The M3 in Upper Manhattan: Weekday bus speed was 5.5 MPH in January 2018 and dropped to 5.2 in October 2021.

- The Q18 in Astoria and Maspeth: Weekday bus speed was 6.6 MPH in January 2018 and dropped to 6.5 in October 2021.

- The Bx36 between Tremont and West Farms: Weekday bus speed was 6.2 MPH in January 2018 and dropped to 5.9 in October 2021.

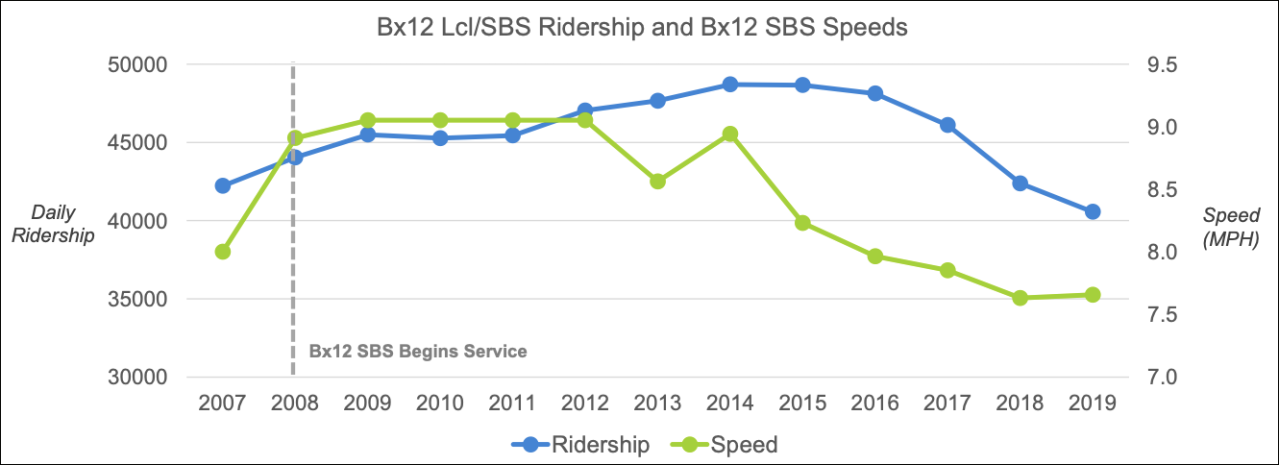

One glaring example of the mayor’s failure is on Fordham Road, a corridor where bus speeds improved under de Blasio’s predecessor, thanks to the addition of Select Bus Service in 2008, but has fallen backwards. Under de Blasio, riders suffered from a lack of attention to detail as bus speeds on the Bx12 SBS declined from a high of almost 9 miles per hour in 2014 to 7.5 miles per hour by 2019 (see the city DOT’s own chart below). The culprits — bus lanes blocked by for-hire vehicles and delivery trucks, and an inability to enforce bus lane scofflaws — mirrored citywide concerns that earned Hizzoner the nickname Bill de Bus-is-Slow.

The problems on the Bx12 and its SBS counterpart have continued, according to the MTA’s speed dashboard. In January 2018, the Bx12SBS had an average weekday speed of 9.4 miles per hour. By October 2021, it had dropped to 9.1. The non-SBS version of the Bx12 started that period at 8.6 miles per hour — and ended at the same slow pace. (It is not clear why the DOT’s speed numbers and the MTA’s differ, though both show bus speeds trending in the wrong direction.)

Sins of the past

Beyond coming into office with an idea of expanding the SBS offerings around the city, the mayor didn’t begin to give buses a second look until late in his two terms. The MTA deserves to shoulder some blame, but advocates and experts say the mayor did not do the most he could do on the roads he controls through his many agencies. The NYPD, for example, was a known and notorious bus lane blocking gang. And the city was asked repeatedly — by he MTA and by bus drivers and elected officials — to install 60 miles of bus lanes outside of SBS routes as far back as 2018. Bus lane mileage, and bus speeds, had never even been a listed goal in the yearly Mayor’s Management Report.

The city also slowly rolled out transit signal priority, the traffic signal upgrade that lets buses get through intersections more quickly by reducing wait times at red lights or extending green lights. People interested in improved bus service were calling for expanded TSP installation in 2014. By 2018 though, the DOT was still insisting on moving intersection by intersection to install the intersection upgrades, a pace that was going to leave a whopping 92 percent of bus routes without TSP by the end of 2020. During the fall of 2020, the DOT finally announced it had moved to a more efficient traffic modeling system and had managed to beat its 2020 goal of installing the upgrade at 1,000 intersections. But ridership was already in freefall by then, years past warnings from activists that bus ridership had “collapsed.”

The years of neglect made it especially unrealistic when the mayor announced in 2019 that he would drag bus speeds up 2 miles per hour in the final 20 months of his administration, with a promise to get them from 8 miles per hour in April 2019 to 10 miles per hour by the end of his time in public service.

“While the de Blasio administration set bus lane records late in its tenure, organizers had to work for several years before breaking through with the idea that better buses are essential to basic equity,” said Riders Alliance Director of Communications and Policy Danny Pearlstein. “The mayor who promised to end the ‘Tale of Two Cities’ took remarkably long to realize that the overwhelming majority of time wasted by slow bus service belongs to low-income New Yorkers of color.”

When the mayor finally tried to start grappling with the city’s tanking bus speeds and ridership, he found a foothold with the 14th Street Busway, which became his signature bus priority accomplishment. The busway, designed to mitigate car traffic and subway crowding during what was expected to be a year-plus shutdown of the L train, was controversial among Village NIMBYs. But the mayor backed the plan through howling opposition and multiple lawsuits, even showing more spine in the fight than transit darling Corey Johnson.

But when the car-free space succeeded beyond the dreams of transit enthusiasts, de Blasio did not move quickly to expand it to other areas, proposing only five short car-light bus zones the next year, and then only ending up slowly doing four of them.

Mistakes of the present

Then — the pandemic. During the lockdown, bus speeds did indeed improve, almost entirely because there were fewer cars on the road to get in their way. In hopes of maintaining the benefits of better bus service after the pandemic, the mayor commissioned a panel experts, which promptly warned him that car traffic would return in even higher numbers and recommended at least 40 miles of emergency bus lanes and busways in 2020 to head off disaster.

The mayor stuck for the more “manageable” goal of 20 miles of bus priority streets, yet still fell short, installing under 16 miles of busways and bus lanes by the end of 2020. The city retreated from its goal of painting 3.3 miles of bus lanes going each direction Hylan Boulevard in Staten Island and went with a 1.4-mile bus lane on one side of the street. Fifth Avenue in Manhattan fell to the axe of small business interests like Armani, Valentino and Rolex. A proposed busway on Jamaica Avenue never got off the ground, and a Washington Heights busway on 181st Street shambled so slowly through the planning process that it couldn’t cross the finish line that year. For all the celebrated talk of bringing 3.5 miles of busways to the city last year, de Blasio’s Department of Transportation only installed 0.8 miles in 2020. In fairness to the mayor, he could have ended the year with 1.1 miles if a proposed busway in Flushing wasn’t waylaid. After Council Member Peter Koo hijacked a DOT informational event to lead the business owning opposition in the racist chant of “BLM stands for Business Lives Matter,” he and his allies won a temporary restraining order against the project, which was lifted in early January 2021.

Eventually, the city managed to install the Flushing, Jamaica and Washington Heights busways in 2021, though it still punted on Fifth Avenue. Ultimately, 2021 was about the missed opportunities of 2020 instead of new ideas or locations for bus priority. On top of that, the expected increase in car trips as the city reopened wasn’t paired with an enforcement effort by the NYPD to prevent double-parking or parking in loading zones or bus lanes.

When he was asked about a multi-year dereliction of duty that resulted in bus speeds falling even below where they had before he took office, the mayor tried a number of tactics to deflect. First, he set the start of the parameters for the bus discussion in 2019.

“We have created busways for the first time in the history of city and, yes, 14th Street has been a tremendous success, but there’s a lot more than that,” de Blasio said during a December press conference [point of information: busways existed in the city before de Blasio]. “The biggest in New York City history, Jamaica and Archer Avenues in Queens, the shape of things to come. More and bigger bus ways, they are nascent. They’re going to have a big impact as they grow. Select bus service, which we’ve deepened is going to have a big impact.”

Seemingly unaware that SBS routes were slowing down by the end of 2019, and that rush hour speeds have fallen from 9.4 miles per hour in January 2015 to 8.5 miles in November 2021, de Blasio inexplicably shifted to saying that after eight years in office his bus improvement efforts had only started so we need to wait things out to judge him. He also blamed a pandemic-era shift to cars (if only anyone had warned him or someone hadn’t told New Yorkers to improvise) and suggested that the NYC Ferry was a solution to speeding up buses:

But it’s impossible to talk about the lasting impact – one, when these things are just starting; two, when the last few years when we’ve done these things have overlapped with a global pandemic, which very sadly has caused many, many people to turn back to their cars. And we’ve talked about it. We’ve documented it. It’s not a state secret. We’ve got to get at people back out of their cars. That’s what’s going to open up the space for the buses…Every time you get people riding a ferry rather than being in their private vehicle, you’re opening up space for buses. Every time we move on important policies like congestion pricing, we reduce a number of cars coming in. It’s all connected. And I think you’re going to see in next few years those speeds go up and more and more people attracted to mass transit.

For their part, bus riders are not ready to extend grace and patience to the mayor, since they’re the ones waiting around for things to get better after eight years. The complaints are familiar to anyone who’s been paying attention to the state of city buses for eight years (so, not the mayor): double-parking in commercial districts and blocked bus lanes leading to excruciatingly long wait times.

“When I use [the B54] after I come for medical appointments for my doctor in Downtown Brooklyn, I have to wait for it at Jay Street for 20 to 25 minutes,” Pedro Valdez-Rivera. “There are a lot of double-parked cars and there’s a lot of traffic. It’s very very slow, especially when you go from the first stop at Jay Street all the way through the commercial district on Myrtle Avenue to Classon Avenue. There’s a lot of double parking there.”

The time that riders like Lopez-Rivera is wasting waiting for the bus is also money, according to congestion expert Charles Komanoff, who calculated that a 0.5 mile per hour drop in bus speeds citywide cost bus riders $170 million in lost time every year.

Haha not haha: a seemingly trivial 0.5 mph drop in citywide avg bus speeds equates to costing NYC bus riders ~$170 million worth of time a year. Seems like neither @NYCMayor, who could give a sh*t, or @GershKuntzman, who does, had an inkling of that. 1/4 https://t.co/G6QSiuJBxc

— Charles Komanoff (@Komanoff) December 15, 2021

Who will save the future?

It’s now up to incoming mayor Eric Adams to fix the traffic mess that’s stealing time and money from bus riders.

“The swings in bus speeds during the pandemic are due mostly to changes in traffic congestion — that indicates the importance of mayoral policy on streets and parking,” said TransitCenter Communications Director Ben Fried. “Mayor-elect Adams has to figure out how to keep the way clear for buses — cameras are not sufficient on their own, and NYPD has proven unwilling to do it, so what’s plan B?”

Plan B can’t only rely on tossing red paint down and calling it a day for one simple reason: Most buses operate on roadways without bus lanes, meaning they are mixed in with regular traffic.

“First and foremost, we have to make sure that the bus lanes aren’t being blocked,” said Tri-State Transportation Center Policy and Communications Manager Liam Blank. “But second to that there has to be a parking reform, so that streets that don’t have bus lanes on aren’t being clogged up by double parking, which seems to happen on almost every street.”

The MTA and the city of course have strategies to combat bus lane blockers. On-board bus lane enforcement cameras are coming to “at least” 600 more buses by the end of 2023, according to the MTA. Those cameras, when combined with fixed bus lane cameras installed by the city DOT, will cover 85 percent of all the 145 bus lane miles in the city.

The camera program itself has worked according to City Hall and the MTA, spitting out almost one million tickets over the last three years and speeding up buses where the cameras do their thing. Additionally, 80 percent of drivers who get such a ticket don’t get a second one. But hundreds of miles of bus routes don’t have red paint — and are wilder and untamed, City Hall needs new and better strategies.

“Most bus routes don’t have bus lanes, and on those streets the rise in congestion and illegal parking is swamping any gains on the bus lane network,” said Fried. “Ride the bus on any neighborhood commercial street — it’s a total mess of double-parking and the bus can barely get through. Even if we build as many miles of bus lanes as London or Paris, it won’t cover most of the bus network — the city will still have to pay attention to managing traffic, parking, deliveries, and curb access on streets without bus lanes. Right now that’s not happening in a serious way.”

The City Council recently made some efforts to get involved in the curb access game, which could make life easier for bus riders down the line. At the end of November, the Council’s Transportation Committee passed a series of bills regulating curb use and expanding loading zones:

- One would require long-term construction projects to avoid blocking the curb zones, allow the DOT to create regulations allowing cargo bikes to use any loading zone and allow the city to prohibit placarded cars from parking in loading zones in the Manhattan central business district.

- Another would require a “public methodology” from the DOT on how and where the agency sites loading zones, and require it to build either five loading zones per year in neighborhoods where the data points to the need for them or 500 across the city every year for three years after the bill becomes a law.

- A third bill would require the DOT to issue a request for expressions of interest to find out who wants to run “micro-distribution centers” in the city, with the goal of establishing a pilot distribution center that uses sustainable modes of transportation instead of large delivery trucks.

Council Speaker Corey Johnson also endorsed a plan from Komanoff that proposed per-minute charges on trucks delivering e-commerce packages in the most congested neighborhoods in the city. That proposal could help spur incoming Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine’s own plans to remake the package delivery environment in the borough. Those changes could speed up Manhattan buses that right now only move at 5.8 miles per hour on average during peak hours (virtually unchanged from January 2015).

For Adams, who’s pitched himself as the city’s efficiency mayor, a multiagency effort on curbside reform from Day One could unlock better bus speeds without the bruising fights or occasional public freakouts associated with bus lanes and busways. But those efforts, which will touch on the overarching goals of fixing the city’s entire curbside parking and double-parking culture, could be perilous as well since it will involve reallocating parking spaces, expanding the amount of paid parking around the city and stepping in to turn double-parking from a tolerated activity bordering on what some people consider a birthright to a widely ticketed offense, while also lacking the photo-op friendly opening ceremonies that elected officials can get when they lay down another mile of red paint.

The mayor-elect’s agenda for the streets hints that he’s eager to help bus riders, and advocates think the wonkier aspects of that agenda, like say creating 80-foot long neighborhood loading zones on every block or converting 780,000 free parking spaces to paid parking or car-share parking spots like the NYC 25X25 report suggests as possibilities, could still generate some ribbon cuttings. Adams, and his new DOT Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez, will have to embrace their inner nerds to sell people on projects that are wonky but can make real material change.

“Trying a new curb design, doing dynamic pricing for the curb, these are things that might be wonky but they could do a whole lot of good in people’s lives and deserve ribbon cuttings just like marquee projects like busways,” said Transportation Alternatives Communications Director Cory Epstein. “If you are creative in messaging, and you’re creative and bold in your execution, you actually should be able to cut a ribbon on projects that are going to improve people’s lives. Because you know how people get around in a safe and equitable way is something that deserves a ribbon cutting, no matter how big.”

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that implementation of the the Flushing Busway was delayed by a lawsuit and a temporary restraining order. Streetsblog regrets the error.