Opinion: Time To Ditch Commuter Railroads’ Outdated Bike Policy

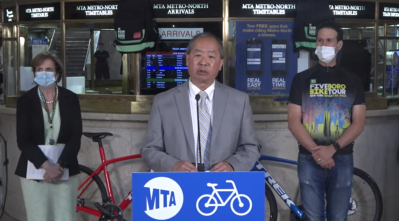

The pandemic provides the perfect opportunity to fix the cumbersome rules of the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North.

As ridership has cratered on the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North during the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people taking their bikes onboard the train has grown. It’s now common to see people walking their bikes through Penn Station and on and off rush-hour trains, a practice the railroad long treated as taboo.

Now is the time that the suburban railroads should revise their frankly anti-bike policies.

Bikes and mass transit go well together — both being more space-efficient and environmentally friendly than car driving. Yet the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has been apathetic (if not outright antagonistic) toward the intersection of biking and mass transit — burdening passengers who want to bring their bikes with complicated rules and restrictions. Bike facilities at stations are frequently an afterthought, if they even exist, with most LIRR/Metro-North stations having nothing more than a tiny open-air bike rack and no secure/sheltered bike parking, while most subway stations have nothing. The situation stands in stark contrast to how systems worldwide (and even elsewhere in America) treat their bike-bringing passengers.

Both LIRR and Metro-North outright ban bikes on all peak trains (when the majority of riders travel) and a number of reverse-peak and off-peak trains, too. The purpose is to keep bikes off “crowded” trains, though even as ridership is drastically lower during the pandemic, the railroads have not formally relaxed the restrictions. Even during normal times, rush-hour LIRR/Metro-North trains seldom reach subway-level crowding.

Both railroads also restrict passengers from bringing bikes on board off-peak trains during a long list of holidays. Restrictions on off-peak trips are even more indefensible, given how the LIRR and Metro-North operate well under capacity off-peak. If a holiday or event would cause crowding, then the railroads should add trains.

The blanket restrictions on peak trains should be eliminated; any restoration should be limited to single-train restrictions, evaluated on a train-by-train basis and designated in the timetable. Off-peak restrictions should be struck: they’re sloppy substitutes for properly planning and delivering sufficient service during times of unusual ridership.

Finally, the MTA should eliminate the requirement that people purchase and carry a bike permit in order to bring their bike aboard a train. Few, if any, other mass-transit operators require passengers to jump through such hoops, and even other MTA operating agencies (e.g. NYCT Subways and Buses) do not require them.

The process for obtaining a bike permit is onerous: There is no way to obtain one online or even at station machines. Applicants must fill out a form, print it, sign it, and either mail it or present it at a ticket office (most of which are now closed) with a $5 fee. If you send it in by mail, you can only pay with a check or a money order and you have to wait two to four weeks until they mail you back the paper permit.

It’s possible to buy a bike permit onboard a train, but that’s also a hassle: The conductor provides an invoice that serves as a one-time permit; one must still present it at a ticket window in order to obtain a permanent permit. Ultimately, the enforcement of the permit requirement varies widely from crew to crew. The policy should have been discarded in the last century.

The COVID-19 pandemic recovery should serve as an opportunity to rethink archaic practices and reform policies to meet the needs of those commuting and traveling today. The goofy MTA railroad bike policies are a great place to start from scratch, and it would be an easy way to promote the use of biking and mass transit for commuting without much of an investment. The installation of bike hooks cost $209,000 for the M-8 fleet, or about $1,000 per car; the LIRR could retrofit its entire electric fleet for less than $1 million.

Like much about the MTA and LIRR, the issues with bikes onboard trains are not about a lack of funding, infrastructure constraints or space. The attitude simply reflects a lack of effort and interest in making biking-and-riding a viable option. The pandemic recovery should be the perfect opportunity to address this anachronism.

The Long Island Rail Road Today blog (@TheLIRRToday) covers issues of metropolitan mass transit. This article was adapted from a recent post.