How the MTA Plans to Harness New Technology to Eliminate Bus Bunching

The MTA is putting serious resources into combatting uneven bus service, hiring more dispatchers and putting displays in every bus that help drivers even out gaps in service.

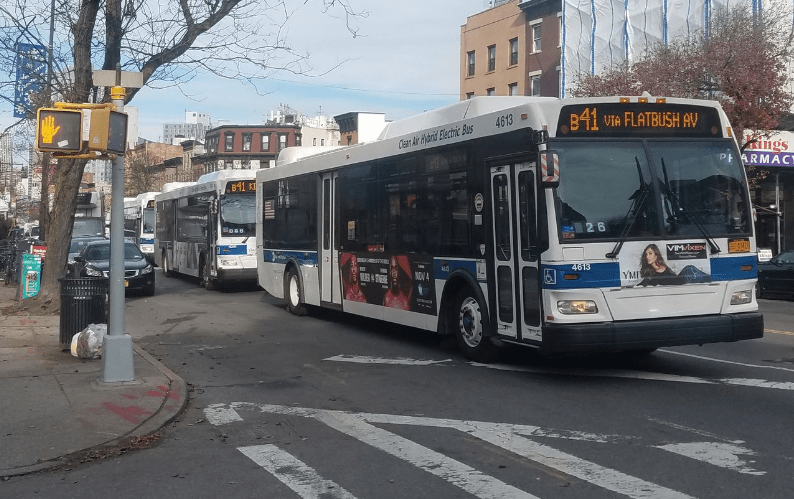

The only thing more frustrating than waiting forever for a bus is waiting forever and then watching two or three buses pull up to your stop at the same time. It’s a symptom of unreliable service called “bus bunching” — and the MTA is embarking on a major plan to prevent it.

With a new command center, more bus dispatchers, and high-tech displays in every bus that will empower drivers to even out gaps between buses, the MTA is putting serious resources (about $300 million) into combatting uneven service.

Bunching is the bane of New York City bus riders because it’s the tell-tale sign of unreliable service. When buses on frequent routes are evenly spaced, riders waiting at a stop can count on the next bus arriving before too long. But when buses arrive in bunches, service is less predictable and some riders get stuck with very long waits.

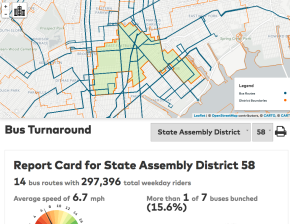

Citywide, one of every eight buses arrives in bunches, or within one-quarter of the scheduled time between buses, according to data compiled by TransitCenter. Say the schedule calls for a bus to come every 12 minutes. If one bus comes three minutes after the previous bus, it qualifies as “bunched.” That’s when the problems start, because some riders will then have to wait 21 minutes for the next bus (assuming it’s on time).

The worst bunching tends to happen on important bus routes with lots of riders. The 20 bus routes with the highest rates of bunching carry an average of 20,000 daily trips.

Bunching is not a problem entirely within the MTA’s control. Traffic congestion and other factors throw buses off their schedules. Bus lanes, congestion pricing, and all-door boarding can mitigate these factors and improve reliability. So can better dispatching and control of the bus fleet once operators are already out on the streets.

“The perfect world is everything is on time,” said Cordell Rogers, who oversees the MTA’s war on bus bunching. “Once we step into the real world, we realize everything is not on time, and then we start managing headways.”

A War Room for Better Bus Service

The MTA is currently building a new bus command center, slated to open in 2020, that heralds a reorganization of how it manages bus service delivery.

Staff will still have to put out the same fires — buses will always need to be re-routed because of collisions, street closures, driver assaults, sick passengers, and myriad other things — but the MTA is assigning many more people to the job.

With an increase in supervisors from 20 to 59, the MTA’s bus command center will be able to pay much more attention to keeping buses evenly spaced. Supervisors, who today track as many as 180 individual buses at once, will handle no more than 100 buses at any given time.

Bus dispatchers will see some technology upgrades before the new command center opens, in the form of an automated dispatching system known as CAD/AVL. Set to launch as a month-long pilot in Staten Island next March, the new CAD/AVL will allow dispatchers to monitor service “down to the block,” Rogers said.

Given traffic-clogged streets, the MTA also needs to be willing to let go of set schedules and dispatch buses in a way that anticipates congestion further down the line, according to TransitCenter’s Chris Pangilinan. If the schedule calls for buses to arrive every eight minutes, for instance, it may make sense to dispatch buses every five minutes when traffic is bad.

Congestion will inevitably slow buses down in the middle of their routes, but smarter terminal dispatching can increase the number of buses arriving on time without the inconvenience of slowing down buses mid-route. “Holding a bus in the middle of the route with a lot of people is in theory a good way to get the gap closed, but there’s a lot of people on that bus,” said Pangilinan. “You’ve got to weigh the pros and cons. The more we can do in the terminals when the bus is empty, the less irritation we cause riders down the line.”

Using daily reports on bus performance, officials could pinpoint where and when slowdowns consistently develop, and adjust dispatching ahead of time.

Empowering Bus Operators

Not all of the adjustments need to come from the top down. Armed with “transit control heads,” iPad-like devices that will be put on the dashboard of every bus in the city, drivers will be able to see the distance between their bus and the buses behind and in front of them, and adjust service accordingly. That could be a seismic improvement for operators, who currently sit at the receiving end of directives from supervisors and managers.

The goal is to “empower… bus operators to better self-regulate,” Rogers said. “Unless you can see the bus in front of you, you don’t know how well you’re doing in terms of headway.”

“What pisses off the bus operator is that someone who doesn’t know what’s going on on the ground calls them up and tells them what to do,” said TWU Local 100 Vice President J.P. Patafio, who heads the union’s bus division. “They see dots and they see bunching, and they call the operator and command him to do something. It’s just frustrating the operator. It’s causing more stress and it’s not serving the public.”

“Bus operators know how to make the system work,” Patafio said. “Give them the right tools, and let them be a part of it.”