How Transit Agencies Can Stop Worrying and Love Bus Network Redesigns

The MTA is preparing a major bus network overhaul on Staten Island, and more changes could be coming to the rest of NYC.

More American cities are coming to grips with the fact that their bus networks leave a lot to be desired. Routes haven’t changed in decades and no longer align with population and employment patterns. Service is allocated inefficiently, arrives too infrequently, and doesn’t connect people to the places they want to go.

Redesigning bus networks, like Houston did in 2015, promises to make transit more useful to more people by expanding where and when they can catch buses that arrive frequently. But it can also make people angry.

Modifying routes and eliminating bus stops unmoors people from their routines, and that won’t sit well with everyone. In Baltimore, a bus network overhaul (which was presented as a consolation prize after Governor Larry Hogan cancelled a light rail project) met with staunch opposition from both riders and operators.

Policy makers who’ve gone through bus network redesigns say some contentiousness is unavoidable, but a well-run process can work through that and ensure that the final plan emerges better for it. Last night, TransitCenter hosted officials from NYC, Houston, Richmond, and Los Angeles for a discussion of bus network redesigns and how to do them right. (Video from the event is available on Periscope.)

By their nature, bus network redesigns create tradeoffs, so it’s important that the improvements feel worth it for riders. And that, said Houston Metro board member Christof Spieler, requires having frank, in-depth conversations with transit riders, not just talking at them.

“I think that’s a kind of conversation transit agencies aren’t used to having,” he said. “We tend to talk in these very generic terms, like, ‘We are trying to improve mobility.’ That’s a meaningless phrase.”

Houston’s network redesign succeeded in part because it touched every corner of the city. “Just about every rider gets a benefit, even if their bus stop might be going away or their route is further away, the rest of their trip is getting better,” Spieler said.

You also have to anticipate and brace for a certain amount of pushback and stress throughout the process. “The agency staff alone can’t do it,” Spieler said. “You need decision makers who are willing to give the staff the room to operate and are willing to get yelled at a lot, in order to actually implement it.”

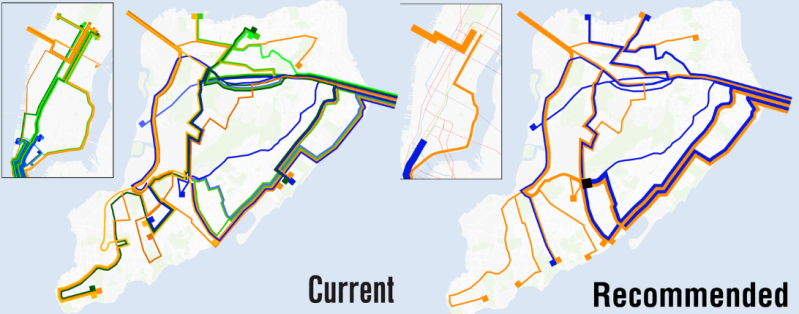

In New York, the MTA is starting with Staten Island. Its relatively small population and self-contained bundle of bus services makes it a good testing ground for redesigning the bus network.

The impetus for the redesign came from conversations with Borough President James Oddo, who remains supportive as the MTA has revealed concrete plans. Agency officials have been meticulous in their outreach, conducting in-person surveys and workshops and presenting the initiative to the editorial board of the Staten Island Advance.

“We’re using the local political network as part of our early outreach,” said MTA Senior Director for Bus Planning Sarah Wyss. The goal is to create a “sense of ownership” among Staten Island residents and leadership.

Advocates have called on the MTA to extend the bus network redesign throughout the other four boroughs. Wyss seemed receptive to the idea while cautioning that it will be more complex than the undertaking on Staten Island.

“Certainly we do need to look at all of our service,” she said. “What we would be really looking at is one network at a time, and the networks don’t necessarily line up with the borough boundaries.”