Bike-Share in The Village: What Would Jane Jacobs Do?

I didn’t get to speak at the Manhattan Community Board 2 meeting last night to discuss bike-share — I stayed outside too long kibitzing on West 11th Street, so my speaker card landed at the bottom of the stack. Here’s what I would have said:

I live in CB 1, on Duane Street, but my first New York apartments were in or just outside CB 2, on West 15th Street and Minetta Street. My kids were born across the street at (now shuttered) St. Vincent’s Hospital. My two sisters lived a few blocks away. And there were timeless evenings at the Village Gate, the Village Vanguard, etc. So there’s a lot of Greenwich Village in me.

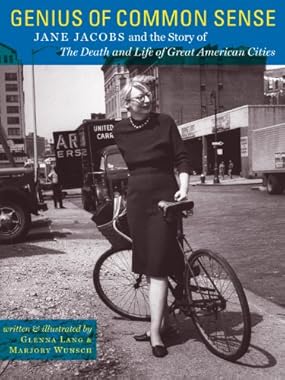

I don’t quite know what to make of the uproar and upset from so many of my neighbors tonight. I think I’ll try to channel Jane — Jane Jacobs, the immortal author-activist who led the insurrection that stopped the Lower Manhattan Expressway and whose “Death and Life of Great American Cities” laid the intellectual foundation for today’s livable streets movement. Jane famously lived at 555 Hudson, a stone’s throw from where we’re meeting tonight. I met her just once, in Toronto, in 1990 or 1991, where Jane had moved in 1968, the year I moved in. Obviously, I didn’t know her well. But I’ve studied her life and her work enough to venture what Jane might want to tell us.

To start, I think Jane would have understood that for Citi Bike to succeed it has to be done “at scale.” So far as I know, Jane didn’t use the term “network effects,” but that idea pervades her work, as blogger Timothy B. Lee points out:

Jacobs doesn’t quite put it this way, but Great American Cities is really a treatise on the importance of network effects to urban wealth creation. The reason people flock to noisy, dirty, crowded cities like New York and Chicago is because most of the things we value are provided by other human beings, and being in a large city puts us in close proximity with many more of them.

Network effects apply to systems as well as populations: Telephone systems are based on them, since the value of your phone depends on my having one as well. Indeed, “network math” posits that while the cost of a network rises in linear proportion to the number of instruments, the network’s value rises geometrically in relation to that number. Just so, with bike-share. A Citi Bike won’t be fully useful unless there’s a full-blown network of stations where you can find a bike and then leave it at the end of the trip.

In short, without scale, forget about bike-share, Jane Jacobs the analyst might have said.

Without question, Jane Jacobs the urbanist would have wrapped bike-share in a bear hug. Jane would have relished the opportunity to always have a bike at the ready and to be unencumbered by it at her destination. She would have delighted in the sturdy, interchangeable and utterly utilitarian machines themselves. And she would have appreciated the access to cycling the system would have provided everyone — not just those fortunate enough to live within easy cycling distance of work, as Jane did, but the throngs of workers and visitors who come in from the boroughs and the suburbs.

Where my channeling gets a tad murky is with Jane’s neighborhood-activist part. I’m sure Jane would have shrugged off the NIMBYs here tonight who kvetch that the bike stations block “their” streets but never organized against the cars that until a week ago filled the same curb space 24-7. And she’d have scoffed at the idea that bike-share users will be endangered by speeding and fast-turning cars and cabs. Why not go instead after the miscreant drivers who threaten everyone? But some of the micro-adjustments sought tonight — a gap in the line of bike docks for a truck loading zone, shifting a station from a side street to an avenue around the corner — might have tugged at her.

Yet on this point, I’ll venture that Jane would have consulted her political part, looked at the calendar, and said something like this:

“Mayor Bloomberg has eight months left, and then he’s gone, along with the political and administrative power to deploy this potentially transformational program. One or two or a dozen siting changes may make individual sense, but to open the program to them now is to jeopardize the intricate schedule of startup and expansion involving hundreds of stations and thousands of docks.

“Robert Moses spent billions and uprooted hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers in a 40-year highway-auto makeover that bled the life out of the city and came this close to turning it into a cadaver. You know this. You know that we fought back. Some of you fought with me, or are the inheritors of those who did.

“We always said that reversing Moses’ monstrous legacy wouldn’t happen overnight. It won’t happen without some pain, either, even some loss. And the restored world won’t look exactly like the old. But it will be a lot better than what he left us with.”

Jane concluded “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” by proclaiming that “lively, diverse, intense cities contain the seeds of their own regeneration.” Thanks to bike-share, New York is poised to become even more lively and more diverse, and to keep on regenerating.