Advocates: State DOT Analysis Engineered to Preclude Sheridan Teardown

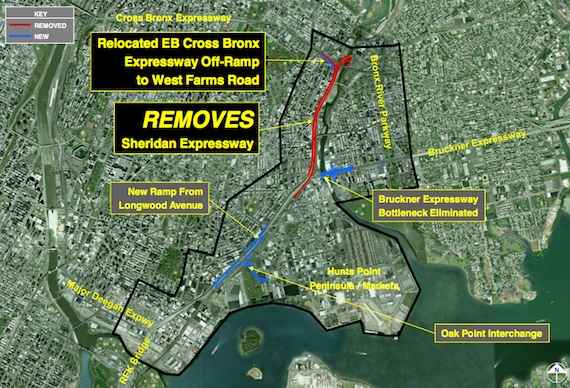

The Sheridan Expressway runs only 1.25 miles between the Cross-Bronx and Bruckner Expressways. This option, one of two remaining alternatives, would remove it entirely. Image: NYSDOT

The Sheridan Expressway runs only 1.25 miles between the Cross-Bronx and Bruckner Expressways. This option, one of two remaining alternatives, would remove it entirely. Image: NYSDOTAt a public meeting last night, the state Department of Transportation released a traffic analysis of the proposal to tear down the Sheridan Expressway, the Moses-era "highway to nowhere" that separates Bronx residents from the Bronx River waterfront. The main conclusion appeared to bode poorly for the plan to replace the highway with housing and parks: According to the state DOT, removing the Sheridan would force traffic onto local streets.

In response, advocates for transportation reform and environmental justice warned about potential flaws in the methodology behind DOT’s traffic analysis. They also questioned the assumptions behind the agency’s impending environmental review, which won’t take into account any of the benefits of what will replace the Sheridan.

The Tri-State Transportation Campaign’s Kyle Wiswall called the

DOT’s environmental analysis

"an exercise in futility" that "seems to be engineered to reach a

preconceived result" — keeping the highway in place.

For years, the state DOT has been studying ways to improve the highway system near Hunts Point, a regional food distribution center that’s a hub for truck traffic. Currently, trucks travel onto the peninsula via local roads, destroying the quality of life for area residents even as the many highway interchanges in the South Bronx — the Sheridan, the Major Deegan, and Bronx River Parkway all run between the Cross Bronx and Bruckner Expressways — snarl highway traffic.

Thanks in large part to a sustained advocacy campaign, under the umbrella of Southern Bronx River Watershed Alliance, the teardown option has gradually gained momentum and entered the official discussion of what to do with the Sheridan.

The DOT has now narrowed their proposal down to two possibilities. In some ways, they are identical. Both would add an exit on the Bruckner that could connect more directly to Hunts Point, intended to keep truck traffic off local streets. Near where the Bruckner meets the Sheridan, it briefly narrows from three lanes to two, before widening again; both plans would add a lane on that segment to eliminate the bottleneck.

But the difference between the two plans is a big one.

One would keep the Sheridan Expressway in place; the other would remove the highway altogether. That would be the first highway teardown in New York since the West Side Highway was removed in the 1970s and 80s. The state DOT will make a final choice in early 2012, according to Gill Mosseri, the project manager with the consulting engineering team.

The Sheridan is only 1.25 miles long and serves as a redundant connection between the Cross-Bronx and the Bruckner. The Major Deegan connects the two only four miles west of the Sheridan, while the Bronx River Parkway connects them less than a mile east of the Sheridan. The Cross-Bronx and Bruckner merge directly only two miles east of the Sheridan. The Sheridan is so underutilized that on some days you can safely stand in the middle of the highway at rush hour.

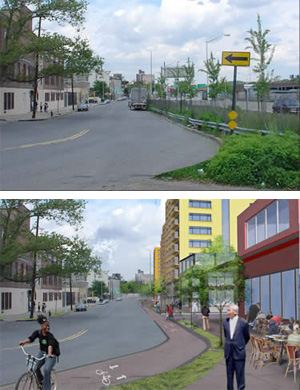

With the highway gone, 28 acres of newly available space could be put to use as badly needed affordable housing or parkland. The Southern Bronx River Watershed Alliance’s community-based plan would replace the highway with 1,000 units of housing and a greenway along the river, creating an estimated 700 jobs.

The Southern Bronx River Watershed Alliance plan to replace the Sheridan with housing, retail, and open space.

The Southern Bronx River Watershed Alliance plan to replace the Sheridan with housing, retail, and open space.Last night, the state DOT released one of its two traffic analyses of each proposal (the second may not be made public at all, according to Mosseri). According to their numbers, traffic in the area is expected to skyrocket by 2030. If the Sheridan is removed, DOT’s model shows a chunk of that traffic being pushed onto local roads, a finding that potentially impedes efforts to tear down the highway.

That analysis may not stand, however. "We’re going to get the underlying data and pick it apart," said Kyle Wiswall. "The last time we did that, we found errors in both the inputs and the outputs." Coding errors and faulty assumptions about how traffic would grow marred earlier traffic predictions, he said.

Though activists haven’t yet had a chance to look at the DOT’s model, Joan Byron of the Pratt Center for Community Development pressed DOT representatives last night about "the meta-assumption that traffic will increase no matter what."

Mosseri responded that the department was using the model recommended by the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council (the region’s federally designated planning body), which assumes that traffic will increase with population.

The DOT now begins preparing an environmental impact statement for each proposal, with drafts expected to be released in early 2011. Because the EIS includes categories like "visual resources," "land-use and social conditions," and "environmental justice," you might expect that document to look more favorably on park space and housing than on a highway. That’s not what the EIS is likely to do, however.

Claiming that there isn’t any official plan for what would replace the Sheridan, the DOT and their environmental consultant argued that they can’t factor in any benefits of what would replace the highway. "You just lose the Sheridan," said Guy Lamonaca, the project engineer with DOT. "Maybe you put up a barrier, you put up a fence."

In other words, said Wiswall, in the analysis, "the removal isn’t a removal. It’s a highway left to rot."

By not assessing any benefits of highway removal, DOT is putting a finger on the scales, argued Byron. She worried that keeping the Sheridan will end up the department’s preferred alternative because DOT’s assumptions will lead to the conclusion that "having a highway is better than not having a highway."

Byron called on the New York City agencies which would have authority over the freed-up land if the Sheridan is torn down — City Planning, Parks, DOT, and the Economic Development Corporation — to intercede with the state DOT and assure them that the land wouldn’t be allowed to lie fallow. "It’s their prerogative to insert themselves into this debate," she said.