OPINION: Center-Running Bike Lanes Aren’t as Good as Proponents Suggest

“Center-running bike lanes” — which run down the middle of the road — are few in number in New York City, but more have been proposed. In a piece in February, Streetsblog contributor Austin Celestin proposed more use of existing medians to add pedestrian space and parkland.

Celestin was right to suggest a more democratic use of medians — many of which are filled with inaccessible greenery or just concrete. But cycling isn’t exclusively the realm of commuters and athletes — most people who bike typically travel short distances, within their neighborhoods, to run errands or visit with friends. Accessing community amenities requires access to the curb — which is where bike lanes belong.

The goal of urban cycling infrastructure is to make cycling a feasible door-to-door (or door-to-transit) transportation option. Most city dwellers live inside buildings, which they access via front doors abutting sidewalks. The purpose of all transportation should be to make it easier to get to those front doors. Center-running bike lanes isolate cyclists from the public realm, shoving them between moving cars and dead space instead.

This is backwards. As a friendly mode well-suited for quick, short trips, cycling should have curb priority over cars, parasites of the public realm that currently take up more curb space yet sit idle most of the time.

Many people bike to get to work, but biking most valuable for short trips — the kind that involves frequent interface with businesses and other destinations along the sidewalk. But a center-running lane primarily serves people who commute 45 or more minutes to work or ride between transit deserts — and is next to useless for someone who rides a bike short distances.

In fact, center-running bike paths have the potential to discourage casual riders by distancing them from the places they want to go. This leads cyclists to ride in ways not everyone may like — such as on the sidewalk — or worse, lead them to choose not to ride at all.

It is harder to browse shops in the neighborhood away from the curb, for example, while spontaneous stops — to window shop for special sales and lucky finds or to grab a snack — are harder for the rider to justify. The dance to cross multiple lanes of car traffic adds an unnecessary, dangerous step for cyclist-shoppers as well as food delivery people who make multiple stops. From a business perspective, that means fewer customers stopping at local merchants. Wherever bicycle parking and safe access are built, cyclists visit and spend more than drivers — making them attractive customers that deserve more attention.

Center-running bike lanes are also terrible for turns. Continuing straight through the median may be easy, but turning left or right is hardly intuitive. Cyclists lined up to make the same right or left turn can also cause dangerous back-ups in the bike lane.

A perfect example of this is the intersection of Delancey Street and Allen Street in Manhattan, where two center-running bike lanes meet. A bike box in the middle of Delancey Street is intended to serve cyclists turning off of both streets, but is often too crowded for more than a few cyclists to make the turn. The rest block incoming traffic.

Curbside bike lanes, in contrast, make room for many cyclists to line up to turn, including when there is a red light.

Bus lanes, on the other hand, belong in the center. Unlike bicycles, buses don’t serve every potential front door, but only stop every few blocks at designated locations. Plus, median bus stops automatically double as refuge islands that make pedestrian crossings safer. Curbside bus lanes, meanwhile, are chronically blocked because there’s nothing keeping drivers (including cops) from parking their cars on them.

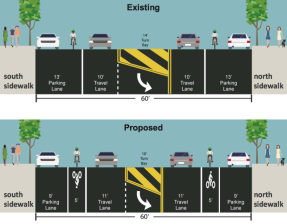

Center-running bike lanes already exist on Sands Street in Brooklyn near the Manhattan Bridge, 108th Street in the Rockaways, and Allen Street in Manhattan, the latter seen as the gold standard because its medians are wide enough to allow public park space. But even Allen Street is surrounded by car lanes that only leave space for narrow sidewalks. Extra-wide sidewalks would better connect the auto-free space to the community around it.

This may be a counterintuitive message to give as our bike network expands at a glacial pace while actual glaciers are melting due to climate change. But the urgency of encouraging cycling doesn’t mean we should settle for suboptimal cycling infrastructure.

Now is the chance to design streets that serve as many people as possible.

Samuel Santaella, a frequent Streetsblog contributor, lives in Queens. His opinions do not necessarily reflect those of the Streetsblog editorial board, but we offer them for perspective.