ANALYSIS: Waste Containerization Will Be Big Lift, But Could Be Historic Change for Trash City

Mountains of trash, mountains of politics.

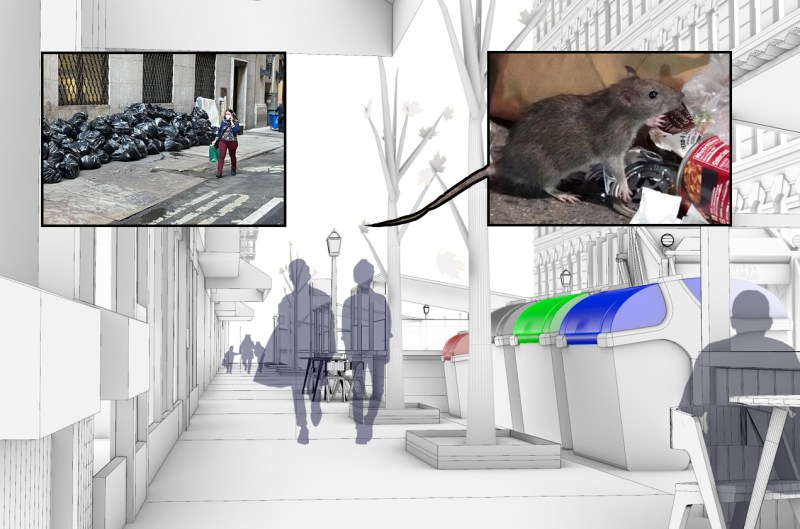

The Department of Sanitation documented in a much-anticipated report that the Big Apple can containerize the garbage that lines city sidewalks, but to make it work, Mayor Adams will have to invest in a wholesale overhaul of the world’s largest municipal trash collection agency and convince New Yorkers to accept the transformation of 150,000 curbside spots in residential neighborhoods that drivers long ago commandeered.

Yes, the city will likely have to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on new trucks that don’t currently exist and deploy hundreds of thousands of new containers across much of the five boroughs — but given how difficult it is for city agencies to remove even one parking space for public benefit in a residential neighborhood, the largest challenge may simply be repurposing street “parking” spaces for the curbside boxes, a factor of 10 more than are currently occupied by Citi Bike docks or outdoor dining sheds.

Even 150,000 parking spaces is still just 5 percent of the total 3 million spots the city currently allocates — largely for free — to car owners, an area equivalent to 12 Central Parks.

Yet even the reuse of a few “parking” spots draws fierce opposition, as when, for example, the city sought to expand Citi Bike into Maspeth and Ridgewood in Queens last year — even though the docks would increase the number of parking spots, just for a different mode of transportation that doesn’t cause dangers to the environment and vulnerable road users.

Also, opponents of the popular outdoor dining restaurant program have twice sued to remove the outdoor dining sheds and restore parking, and the Council has been reportedly eyeing reverting year-round curbside eateries to just a pilot.

Even installing loading zones so trucks can make deliveries without double parking have faced opposition from the city’s car-owning minority.

“Parking-driven psychosis is a regular feature of American life,” journalist Henry Grabar argues in his new book, “Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World.” Drivers, he added, “expect parking to be immediately available, directly in front of [their] destination, and most important, free. This is unique. It would be unimaginable to hold any other good or service to the same standard.”

Meanwhile, safe streets advocates, waste experts, and residents in the pilot zone cheered DSNY’s effort to advance containerized collection, which has long been established in other global cities like Barcelona, Paris, and Buenos Aires — but they agreed that the hard part starts now for city leaders.

“Sanitation is a very basic function of the city — for people who have cars or not — and people usually put that as the very top of the list,” said Christine Berthet, who worked on an earlier containerization test with DSNY and is a founder of the pedestrian advocacy group CHEKPEDS. “I think it’s really a step in the right direction and if they keep at it, it could be really transformative for the city.”

Different strokes

Sanitation’s nearly 100-page study [PDF] found that containerization — with either large stationary bins to collect the garbage of multiple homes or individual rollable bins, depending on the neighborhood density — could work in 89 percent of the city.

Some neighborhoods would get double the collection frequency to keep the bins from overflowing, and the report said that the enclosures would never take up more than 25 percent of a given block’s curb space. (Anything more was defined by the DSNY as not “viable” for containerization.)

Individual wheeled bins would work in 50 percent of the city, the agency said, citing neighborhoods with single-family homes or buildings up to six-stories. Those bins would continue to inconvenience pedestrians, albeit with the advantage of not providing feeding grounds for rats; car owners would not be asked to sacrifice any space in those areas.

Higher-density neighborhoods — comprising roughly 39 percent of the city, according to the agency — would get shared containers in the curbside lane long-ago seized by drivers.

Another 11 percent of the city is so dense that containerization would either require more-frequent collections or taking up more curbside space than the agency’s 25-percent viability threshold.

But some mid-density areas with up to six story row houses should still get shared containers in the curbside lane, rather than lots of wheeled bins on the sidewalk, said Clare Miflin, an architect and the founder of Center for Zero Waste Design.

Take Brooklyn’s Vanderbilt Avenue, where Miflin’s organization recently showed that curbside boxes could efficiently containerize trash even for three- and four-story walkups.

“It’s a real advantage, especially if you have four bins per building, that’s a lot of bins on a block. Shared bins have a lot of streetscape advantages,” Miflin said.

DSNY’s report agrees to some extent. A rendering evaluating the smaller wheeled containers versus stationary ones showed that using more of the roll bins would create “impassable sidewalk conditions” on a block of five-story buildings:

Agency spokesman Joshua Goodman said that the report studied whether containerization could work, but didn’t definitively determine where stationary bins would end up going.

“The question of what, specifically, is best for each block will be an ongoing one,” Goodman said.

The report said the containers must be able to hold 150 percent of the current waste output in the city “to allow for future growth,” but Miflin countered officials should aim to lower New Yorkers’s trash production not account for a one-and-a-half-fold increase.

“If we put so much [resources] into waste reduction, reuse, community composting, volume reduction, we could actually do it for half the cost and with half the parking spaces,” she said. “So people can get behind that.”

The agency also accounted for larger needs during service interruptions that could cause bins to fill up above normal amounts, Goodman said.

“We do not want to build a system that hopes for something we cannot control — we have an obligation to provide the free, unlimited service of trash collection,” the rep said. “It would be absolutely inappropriate for DSNY to design a containerization program that accounted for less trash than historical data suggests will be produced each day. The excess would simply end up back on the sidewalk.”

Truckin’

The agency will have to revamp its massive collection truck fleet and introduce haulers that mechanically lift the curbside containers, so-called automatic side loaders.

Side loaders are used in some suburban and rural areas in the U.S., but they are largely in the private sector and collect trash from metal dumpsters off-street, which the report describes as “primitive, prone to rust and breakage,” and “extremely loud,” when collected.

The report can’t include sound, so to showcase this point, Goodman sent over several videos of existing side loaders in the U.S., such as this one in the city of Blythe, Calif. (Warning: It’s a bit loud):

Cities in Europe use more lightweight side loaders, which DSNY believes would be the best way to scale the method here, but those vehicles don’t meet our federal, state, and local emissions safety standards so they can’t be imported, according to the report.

Here’s a video of a relatively quiet side loader truck in Barcelona for comparison.

DSNY sets its own size requirements for trucks to navigate the city’s streets and fit in its garages, but there are also differing technical standards between European and American trucks that make adapting European truck bodies to American chassis complicated the study says.

Trucks in the US and Europe use different standards for their hydraulic, electrical and computing systems, as well as their axle loading and weight rating, according to the report, so to import the old-world heavy haulers over here would require “significant modification and adaptation,” according to the report.

The agency also repurposes its vehicles as snow plows in the winter, so any new truck would have to be able to do serve that double purpose as well.

Designing, testing, and launching a side loader for DSNY’s needs will take at least three years and require “significant capital investments,” according to the report.

The city currently pays between $450,000–$490,000 per Sanitation collection truck and has a total fleet of 2,200 of those vehicles. Replacing all the trucks would cost more than $1 billion, though trucks are routinely replaced as they age beyond their work life.

Any lucrative contract to design and build DSNY’s fleet of the future will likely spark fierce competition among trucking companies vying to break into the largest market in the country.

Agency leaders said it was too soon to estimate costs for the entire citywide containerization effort.

The New York City Housing Authority is also piloting containerized garbage collection at its Coney Island developments, likely next year.

NYCHA is using different hoist-lift trucks, but the DSNY report discarded those vehicles as a citywide solution, because they were worried about clearance for the crane and lifting the containers over cars and people in the city’s busy streets.

Commercial concerns

Of the 44 million daily pounds of trash New York produces each day — the weight of about 140 statues of Liberty — more than half, or 51 percent, is commercial waste, which is collected by private carters who are not part of the city’s containerization plan.

Business use a network of more than 90 companies to collect commercial trash, and one business might use a different carter from its neighbor, making it challenging to introduce shared containers.

The city is working on dividing the city into 20 commercial waste zones with no more than three private garbage collectors per zone, but that will still leave some overlap between businesses and make containerization difficult, according to the report.

The study proposes to bring individual bins to small mom-and-pop shops that face the street, possibly through a city rule change, and incentivize developers of large commercial buildings to carve out space for containers on their property.

But Berthet, of CHEKPEDS, worried that DSNY did not have enough concrete proposals to box up the garbage as it proposes for residential waste.

“That means that we are still going to be at seven o’clock having pounds of disgusting stuff on the sidewalk. They are going to have to address that somehow,” Berthet said.

West Harlem pilot

DSNY’s first foray into containerized mechanized collection will be a pilot program this fall in Manhattan’s Community Board 9, where New York’s Strongest will use retrofitted collection trucks to lift wheeled containers stored in the road along the curb.

The program will launch at up to 10 residential blocks and could come to all 14 public schools in the uptown district.

The agency will have to tackle the political third rail of removing parking, with an added challenge: dozens of spaces in the neighborhood are reserved for city workers using placards to park in designated areas or illegally.

On one block of W. 123rd Street, between Morningside and Amsterdam avenues, there are several schools, and with them, rows of cars with placards on the dash. Most of the block is reserved for Department of Education staff, but some drivers also left their cars illegally in No Standing zones.

Citywide, 50,000 Department of Education staffers have placards, and an estimated hundred thousand more city employees have the privilege — one that their unions will be reluctant to relinquish, if the past is any predictor.

DSNY Commissioner Jessica Tisch and Council Member Shaun Abreu visited the block with advocates in the fall to see the huge piles for themselves.

Grateful to the residents who let me know where garbage was piling up on our streets.

Tonight, @NYCSanitation Commissioner Tisch and I joined those constituents to see the spots.

We’re gonna make sure the trash gets picked up in District 7. pic.twitter.com/7j6U7Cpdzv

— Shaun Abreu (@ShaunAbreu) November 16, 2022

Abreu on Wednesday wrote a series of social media posts showing his support for the local project, but despite the lawmaker’s backing, officials will have to face down some residents that have long opposed taking away space from cars — even if it was to bring life-saving street upgrades to the neighborhood.

Ok, Upper Manhattan, you asked for it.

You tweeted at me, called my office, pulled me aside on the streets, and sent me some of the most disgusting pictures I’ve ever seen.

So we’re going to do it. We’re going to start containerizing our trash. 1/https://t.co/ZPkJWkQJPd

— Shaun Abreu (@ShaunAbreu) May 3, 2023

CB9 has a history of favoring space for cars over crucial street safety measures in the area, such as when it repeatedly rejected a road diet for a dangerous stretch of Amsterdam Avenue.

The board did not respond to requests for an interview by press time.

One teacher leaving a school on W.123rd Street on a recent afternoon, who asked not to be named, told Streetsblog removing parking spots “might be frustrating” for her colleagues that commute by car. And that’s from a teacher who doesn’t even drive herself.

The streets schools already use a designated area on the curb to store garbage for pickup in dumpsters, but some of it still ends up on the sidewalk.

Another resident in the uptown district, where 79 percent of households don’t own a car, said that the loss of car space is a worthy tradeoff to clean up the area, which is also one of the city’s so-called rat mitigation zones.

“I’m a car owner that street-parks, I’m totally fine with it,” said Esther Yoon. “There’s gonna be a lot of grumbling and people are going to be protesting, but you know what, at the end of the day we have to do something about this health situation we have.”

Mayor Adams earmarked $5.7 million over two years in the budget for the pilot.

Berthet, who has long advocated for more pedestrian space, said that there will be people who want to keep parking, but that officials should push through the overhauls that will benefit more New Yorkers.

“They will probably make a case saying, ‘Put it on the sidewalk,’ and then it’s ridiculous because you can’t walk,” she said.

The citywide changes will still be years off and require large sums of investments, but the public space booster was optimistic that the city can change its ways.

“Bloomberg succeeded in having people stop smoking, so to me it’s a little like that, it’s of this magnitude and it has been done,” Berthet said.