West Harlem CB Members to DOT: Let Drivers Use Neighborhood as Shortcut

Riverside Drive in West Harlem is shaping up to be another test case for DOT’s commitment to safety improvements, and whether the agency will allow ignorance of basic street design principles and fear of change guide its decisions.

DOT didn’t put bike lanes in its road diet plan for Riverside Drive. Now, key members of Community Board 9 don’t want a road diet in the plan, either. DOT says that without the lane reduction, which will lower the design speed of the street, it won’t go along with requests to reduce the speed limit on Riverside to 25 mph.

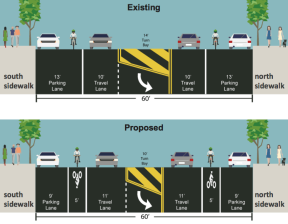

The project includes pedestrian islands and curb extensions along Riverside Drive, 116th Street, and 120th Streets between 116th and 135th Streets. Its centerpiece is a road diet, from two lanes in each direction to one, on the viaduct that carries Riverside over West Harlem [PDF].

CB 9 transportation committee chair Carolyn Thompson and Ted Kovaleff, who served as CB 9 chair in the 1990s, spent much of Wednesday night’s meeting trying to maintain as many car lanes as possible on Riverside Drive.

Kovaleff said that he used to frequently drive to Vermont on Friday afternoons, and found that spillover traffic from the West Side Highway would clog Riverside, backing up on the viaduct. Removing one lane, he said, would lead to total gridlock. DOT project manager Dan Wagner said his analysis showed the viaduct road diet would slow driver speeds without leading to excessive back-ups, but Kovaleff wasn’t convinced. “It would become a terminal bottleneck,” he said, “and that bottleneck would lead to increased pollution.”

“The asthma rate in this community, it’s horrible,” Thompson added. She also claimed that buses wouldn’t be able to operate on the viaduct with one lane in each direction.

Kovaleff didn’t evince much concern about dangerous speeding on the viaduct — and wasn’t convinced, despite ample evidence, that road diets work. “If people are gonna speed, whether it’s one lane in each direction, or two lanes in each direction, they’re gonna press down on the accelerator,” Kovaleff said. “And, you know, I don’t really care if people go 50 miles an hour on the viaduct.”

The viaduct, it turns out, is the most dangerous stretch in the Riverside Drive project area. Outside the viaduct, from 116th Street to Grant’s Tomb, ranks in the middle third of Manhattan corridors for crash rates, Wagner said. When the viaduct is also taken into consideration, from Grant’s Tomb to 135th Street, the project area jumps into the top third of the borough’s most dangerous corridors.

![No bike lanes, and maybe not even a road diet, for the Riverside Drive viaduct. Photo: DOT [PDF]](http://www.streetsblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/riverside_DOT-300x237.png)

Martin Wallace, another committee member, said he cares quite a bit if drivers speed by him on the viaduct when he bikes on Riverside. He also suggested that the board ask DOT to test out a road diet on Riverside and remove it if the change did end up worsening traffic backups.

Kovaleff asked if DOT could simply reduce the speed limit on Riverside without a road diet. After the city’s default speed limit was lowered to 25 mph, DOT kept the 30 mph signs up on Riverside. Council Members Helen Rosenthal and Mark Levine have asked DOT to bring Riverside in line with other city streets, and DOT said last month that it would change the speed limit as part of this project.

On Wednesday, Wagner noted a caveat: the speed limit change could only happen with the road diet, not without it, he said. Board members were skeptical, given that DOT has established 25 mph speed limits on other roads with similar designs.

“The request for 25 miles an hour has been very loud and very heard on Riverside Drive. That indicates to us that this street should be a neighborhood street rather than a commuter street,” Wagner said. If the community board were interested in a road diet along the entire length of Riverside, he said, “we would be receptive to that request.”

But Thompson and Kovaleff seem intent on maintaining Riverside as an attractive shortcut when the West Side Highway is congested. “It may not supposed to be [a commuter route],” Kovaleff said, “but the fact of the matter is that it is.”

“People do use it as a cut-through,” Wagner countered, “and with design changes we hope to change that for the betterment of the neighborhood.”

Kovaloff also expressed skepticism about a curb extension on the southeast corner of Riverside and 116th Street, claiming that squaring off the corner adjacent to a curved building will “have a possible negative impact on the way the building looks.” He also repeated his call, from last month’s meeting, for DOT to eliminate pedestrian islands planned for 120th Street and use the space for angled parking, to squeeze in more car storage space.

The CB 9 transportation committee has tentatively scheduled another hearing on the plan for March 5. Wagner said funding requirements mean that DOT must start construction by September, with work to finish in 2016.