Opinion: Here’s Why I am Against ‘Narc Urbanism’

A proposed City Council bill would let civilians report cars illegally and unsafely parked in crosswalks and bike lanes and then collect 25 percent of the resulting ticket fees. The bill has advocates and urbanists buzzing, but it’s a bad idea, says this opinion writer. All opinions are those of the writer. Streetsblog advocates for a broad discussion of the issues, even if our editorial board takes a different position.

We all want a livable city, but if we’re going to make a livable city worth living in, we are going to need more solidarity, not less.

Intro 501, introduced by Council Member Lincoln Restler (D-Williamsburg), is intuitively appealing: it promises beleaguered pedestrians and cyclists the opportunity take enforcement matters into their own hands.

And the need for action is evident, as New York’s streets grow increasingly dangerous for these groups. Through Nov. 22 this year, there have been 82,303 reported crashes in New York City — roughly 252 every single day. Those crashes have injured 4,227 cyclists and 7,060 pedestrians, killing 12 bike riders and 91 walkers.

As for proof of concept, Restler’s approach is based on the Citizens Air Complaint Program, also known as the “Billy Never Idles” program, which allows residents to collect a portion of any ticket issued to an idling truck they report.

But I believe that turning citizens against one another, even in the name of pedestrian safety, is a terrible mistake.

For one thing, setting neighbors against one another creates the conditions for direct conflict: As one idling program participant told CNBC earlier this year, “[E]very time I go out of my house, I am prepared for an assault.”

But beyond any individual confrontation is the risk these laws pose to greater social cohesion. American society is already fractious enough: interpersonal trust is sharply deteriorating as real-world social networks decline, and rising distrust in our institutions and media make consensus increasingly challenging. Bills like Intro 501 further the trend toward mutual mistrust, hardening existing us-versus-them dynamics in our shared public spaces by creating a narc economy with serious financial incentives and penalties.

Proposals like Intro 501 turn the “eyes on the street” concept, popularized by New York City urbanist Jane Jacobs, on its head. Jacobs envisioned mutual protection from urban crime through a deterrence system derived from social cohesion and lively, busy streets, but Intro 501 conceptualizes the city as a space of enmity and rivalry; a formalized panopticon of citizen surveillance conducted by other citizens.

A cautionary tale comes from South Korea, where this type of citizen-led surveillance has a longer history and is used to police a wide array of infractions. A 2011 New York Times article on the practice paints a grim picture of the resulting tensions. For lack of better-paying alternatives, many individuals “roam cities secretly videotaping fellow citizens,” and some derive their incomes exclusively from citizen-surveillance programs. “Some people hate us,” one of these men told the Times. “But we’re only doing what the law encourages.”

Deputizing citizens to address traffic violations also implicates the many ethical issues attendant to privatized and citizen-led law enforcement. America has a long history of errant and racially biased community policing, from the breathless paranoia displayed on apps like NextDoor to the sometimes-deadly overreach of Neighborhood Watch programs. Given these biases, it is likely that Intro 501 would disparately affect already marginalized New Yorkers through differential reporting rates.

Despite the foregoing risks of violence and social harm, there’s still no guarantee Intro 501 would genuinely improve pedestrian and cyclist safety. At best, citizen reporting schemes are post-hoc solutions — by the time any fine is issued, the damage has been done. The theory is that receipt of a ticket will discourage future infractions, which may happen in some cases, but as Streetsblog has reported, a significant number of parking and moving violation summonses are never even paid.

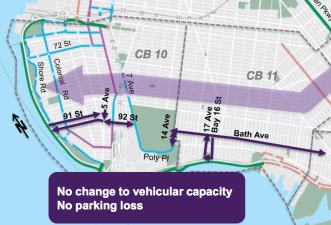

So given all of Intro 501’s flaws, it’s worth asking why the City Council would create a new citizen-led surveillance program rather than roll out proven design solutions that would proactively limit dangerous interactions between cars, pedestrians, cyclists, and buses?

It’s because real solutions are hard.

Intro 501 and similar proposals represent a cynical approach to city governance. Taking direct action to mute the steady drumbeat of road violence might require capital expenditure, angering some voter bloc, or stepping on the toes of an agency under mayoral control. It’s simply easier for Restler and the bill’s co-sponsors to pit their constituents against one another and hope for the best. But by devolving responsibility for street safety to cyclists and pedestrians, Restler abdicates the role of government and places the burden — and by extension, the blame — back on the victims.

Restler’s bill is even more cynical than it appears because the proscribed violations, like blocking a sidewalk or a bus lane, are already prohibited by city law. But the NYPD, tasked with traffic enforcement, has made a point of shirking its traffic-safety duties. Don’t ask Intro 501’s backers to do anything about the NYPD’s disinterest in Vision Zero, though: it’s telling that Restler and the majority of Intro 501’s co-sponsors voted in support of the 2023 budget that increased the NYPD budget at the expense of public education and other vital city functions.

Our cities face real challenges, from pedestrian safety to housing shortages and decarbonization. We’re going to need to work together to solve these problems — we can’t tattletale our way out of them. And we’re going to need leaders willing to leverage the power of the state to do what’s right, even when it’s difficult. Those who would undermine social cohesion in order to seek small gains should think hard about whether government is the right place for them.

As one idling law participant user told CNBC, “You have to go out expecting there’s going to be a confrontation.”

That’s not the kind of city we should be striving for.

MJ Barnett is an avid cyclist and attorney in Brooklyn. You can follow him on Twitter @mj__barnett.

Update: An earlier version of this story had an assertion about violence that was taken out of context and was removed.