We’re not ready for the next Sandy.

Ten years ago on Oct. 29, the superstorm with the beachy name made landfall in New York City, destroying hundreds of homes, killing dozens and grinding the city’s economy to a halt. The storm also upended the city’s transportation landscape, with subway flooding so severe that the system needed days to recover. The superstorm’s path of destruction and the resulting gridlock and transportation problems meant that the city and state also needed to think about how to prepare for the next storm, and think they did in the form of series of reports, one each from researchers at NYU’s Rudin Center for Transportation, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo and then-Mayor Mike Bloomberg.

The reports came from different areas of civil society, but all three touched on some of the same conclusions on how to be prepared for the next superstorm and future flooding: flood prevention in and around the subway system, bus and bike priority infrastructure to help pick up the slack for a disabled subway system, improved subway access and technology, and, more ferries. But 10 years after the storm, how have the city and state fared in actually taking the advice of Cuomo’s “NYS2100 Commission,” Bloomberg’s “A Stronger, More Resilient New York” and the Rudin Center’s “Transportation During and After Sandy“?

Cuomo and Bloomberg’s reports didn’t only encompass transportation issues, but did spend plenty of time talking about how to ensure people could get around during an emergency, while the Rudin Center report, as per its title, focused on transportation issues only.

How well did the reports do in staking out territory? Quite well. How well did our leaders to in implementing the recommendations? Well, our system doesn’t make long-term accomplishments very easy. As such, we’re not there yet.

“Although there has been considerable progress to reallocate street space from cars to low or no carbon transportation in the past 10 years, the city has been too slow to implement projects that will reduce transportation emissions to reach our 2050 goals and protect our infrastructure from climate impacts,” Comptroller Brad Lander told Streetsblog in a statement. “DOT has spent 47 percent of its Sandy recovery grant funding, compared to 73 percent for the city overall as well as demonstrated that nearly 80 percent of our transportation and utility land lies in the 100-year floodplain. … Our subway and street networks are extremely vulnerable to heavy rains and flash flooding as Hurricane Ida demonstrated.”

Our short political cycles have hindered us from creating a long-term plan to deal with the reality of climate change, and the pressure is on. ?? https://t.co/yLpQOWJpMi

— Antonio Reynoso (@BKBPReynoso) October 25, 2022

The city’s and state’s failures to follow the report recommendations also meant the region is fighting a two-front war against flooding related to climate change.

“In our Ten Years After Sandy report, our office demonstrated that nearly 80% of our transportation and utility land lies in the 100-year floodplain,” said Comptroller Brad Lander. “While these decade old reports only did risk assessments on coastal storm surges, our subway and street networks are extremely vulnerable to heavy rains and flash flooding as Hurricane Ida demonstrated,” The climate crisis is moving faster than we are and our transportation network needs to be shored up against increasingly intense storms,”

So here’s a report card of how well we’re doing:

Bus Rapid Transit

Cuomo’s panel of experts wrote that the then-new Select Bus Service was a good start for both high-speed buses and public transit redundancy, but the state needed to upgrade the SBS system into a “true” bus rapid transit system that would be as effective as “a train on rubber wheels.” SBS did expand in New York, but the big idea of a bus rapid transit system with physically separate bus lanes has never managed to take root.

For Cuomo, the NYS2100 report was the last time he ever put his name on an idea for SBS or BRT service as opposed to aesthetically pleasing buses.

The Rudin Center and Mayor Bloomberg also recommended investments in bus rapid transit, though Sarah Kaufman, one of the authors of the NYU report, said its authors were talking about Select Bus Service using the parlance of the time, since “true” BRT would never happen in New York because it lacks the sidewalk space for a traditional customer queue area.

Bloomberg’s report was more precise, recommending expanding the city’s Select Bus Service routes. Maybe Bloomberg recognized it would be impossible to actually build physically separated bus lanes in a city where elected officials rend their garments over painted bus lanes, or maybe he lacked vision. Either way, the BRT question was left to his successors.

Bill de Blasio took office in 2014, and advocates pushed for a BRT route down Woodhaven Boulevard, which didn’t happen despite a slick YouTube video showing its utility. De Blasio instead took a page out of Mayor’s Mike’s book and focused on expanding SBS routes, which grew from six to 20 routes under de Blasio. But in a perfect encapsulation of the old New York City/MTA relationship, in 2018 the MTA announced it would stop creating new SBS routes, less than a year after de Blasio promised to create 21 new ones 10 years. De Blasio managed to install five short car-light busways in the back half of his term, but ultimately left office with critics saying his office had an overall lack of vision on bus priority.

Eric Adams came into office with an ambitious promise: “We should make SBS service the baseline for bus service, and take advantage of opportunities for true BRT. … We must create a BRT system that doesn’t simply connect communities to Manhattan but to communities within boroughs and interboroughs.” Since taking office, none of Adams’s bus lane proposals has reflected that promise, and questions remain about whether he’s going to actually install the 20 miles of bus lanes he is required to install in 2022.

GRADE: D

Emergency transportation solutions for bikes and buses

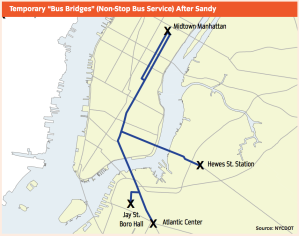

One of the successes of the post-Sandy streetscape was the MTA and DOT partnership on “bus bridges,” the agencies’ replacement for subway service between Brooklyn and Manhattan. As the NYU Wagner report notes, the MTA was able to get 3,700 people per hour between Brooklyn and Manhattan on buses thanks in part to exclusive bus lanes on the Manhattan Bridge partnered with bus exclusivity from Atlantic Center as well as high occupancy vehicle lanes on the Williamsburg Bridge, all of which were enforced by the NYPD.

Both the Bloomberg report and the NYU report also noted the importance of bike infrastructure when the subway system was getting repaired. Bike crossings on the East River bridges more than doubled from their typical 3,500 per day to 7,800 on Nov. 2, four days after Sandy. The NYU Rudin Center report also found more people willing to travel by bike. In a survey that looked at travel patterns to work before and after Sandy, cycling went from 14 percent to 18 percent of mode share among the small percentage of people questioned. The survey itself was small, but the 28-percent increase in cycling showed that people were willing to switch to biking and provided a reason to build out more routes for it.

The success of the bus priority measures and the spike in people choosing cycling led the mayor and the NYU researchers to recommend that the city establish effective temporary transit and bike solutions, as well as invest in better bike infrastructure as a general policy idea.

The city has taken positive steps on bus and bike infrastructure since 2012. The de Blasio administration installed over 20 miles of protected bike lanes per year between 2017 and 2021, and the city succeeded in laying some groundwork for cycling to be an emergency option for New Yorkers, as the bike network that was built helped spur an increase in bike trips over the East River and frequent record-setting days on Citi Bike.

But the network still couldn’t move citywide bike mode share above 1 percent since 2013, while rider safety backslid and efforts to make car driving an unattractive option failed; driving remains up and 26 cyclists were killed on city streets in 2020 and 19 were killed in 2021. So far this year, 14 cyclists have been killed.

The city also seemed to ignore every lesson related to traffic management after the storm when it began to reopen the economy coming out of the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic. On the cycling front, the city established emergency bike lanes of varying quality, but wasn’t able to work at the levels of peer cities who sped up their bike lane implementation plans during the days of reduced traffic.

“It was a point in the administration when the mayor was sort of listening to the police department and nobody else,” said Bike New York Director of Advocacy Jon Orcutt. “The pop-up bike lanes were defined by barrels that one small person can move with one hand. So they got moved, and they didn’t get put back. And the police didn’t care.”

On buses meanwhile, bus use fell from 788,788,420 bus riders in 2012 to 677,588,084 in 2019, a symptom of a lack of a cohesive bus vision from de Blasio. The mayor also convened and then ignored a surface transportation panel that recommended many of the things that the city was supposed to have plans for after Sandy, especially HOV lanes and quick rollouts of bus and bike lanes.

“At the NYU Rudin Center, we made recommendations both after Sandy in 2012 and in the Covid world of summer 2020,” said Kaufman. “Surprisingly, many of the recommendations remained the same eight years later.”

And speaking of HOV lanes, city leaders still won’t embrace car-pool lanes when the idea is floated during every UN General Assembly week and during “Gridlock Alert” days, and they were totally dismissed as a traffic reduction when New York City began coming out of the depths of the pandemic. Maybe we’ll get it right during the next emergency.

Given the current state of New York City’s congestion and the failure to significantly raise bike mode share, the city gets a middling grade.

GRADE: C-

Subway flood prevention

A lot of print and pixels have been used up on the MTA’s large and expensive efforts to rebuild and prepare the subway system for future flooding, including refurbishing flooded East River tunnels, repairing and hardening train yards and repair shops around the city and shoring up A train links to the Rockaways. But as noted in both the Cuomo and the Rudin Center reports, the MTA also had to prepare for a world when subway flooding would happen again (and again and again). An MTA spokesperson said that the agency has followed up on recommendations from the Cuomo panel to install roll-down doors at subway entrances and mechanical vent closure systems underground to keep water from getting in through ventilation shafts, and backup generators for pumps that can work even when localized power outages happen, recommended by both the Cuomo and Rudin reports.

An authority no less than the MTA Inspector General gave the agency good marks on its flood preparation since Sandy, noting that the NYC Transit has installed more than 2,200 mechanical closure devices on air vents, almost 700 deployable vent covers, 150 watertight hatches and marine doors respectively and about 75 flexible anti-flood gates at subway entrances and garage openings. The IG did recommend that the MTA “should establish a method for ensuring adequate staffing and training of the field crews that must deploy devices in preparation for a storm,” which the agency agreed to do by formalizing the training on the devices by the end of 2023.

The reports from Cuomo’s panel and the Rudin Center did point to flood prevention as a goal even outside of storm surge. Cuomo’s NYS2100 panel, for example, recommended investments in green infrastructure to absorb excess rain, while the Rudin Center report recommend that the MTA raise entrances at the low-lying subway stations that were prone to flooding, pointing out that transit agencies in Bangkok, Paris and London did to prevent excess water from getting into the system. There are 472 subway stations and 290 are below ground; the MTA started projects to build raised entrances at 45 more since 2022.

But as we saw in 2021 with floods caused by torrential rains from the remains of Hurricane Ida and then impactful but less severe subway flooding from heavy rain in June 2022, the city and MTA aren’t ready for flash flooding, and not enough was done on that front in the intervening years between Sandy and Ida. The city has laid down over 660,000 square feet of porous surfaces on streets and sidewalks and built over 11,000 curbside rain gardens in what former Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Vincent Sapienza called “the most aggressive green infrastructure program in the country.”

In the aftermath of that flooding, experts say it’s time for the city to think about bigger and bolder water numbers.

“The goal of managing 1.7 billion gallons a year of stormwater by 2030 was put in place in 2010, and the whole framework and goal of managing that amount was decided based on water quality concerns, not necessarily in flood risk concerns,” said Regional Plan Association Senior Researcher Marcel Negret.

A previous RPA analysis of just Central Queens stormwater management found that just that part of Queens needed 40 times as much green infrastructure it had to manage future flooding from stormwater, which demonstrates the task ahead of city and state leaders.

“We do need to build rain gardens, but the number we need is not 11,000. We’re talking about orders of magnitude more when we talk about the volume of stormwater management,” he said.

The good news though, is that the city and MTA is working on it. MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber formed a cross-agency resiliency task force, with representatives from the MTA, the city DOT and city DEP. That task force has allowed for interagency coordination on needed anti-flooding measures like clearing catch basins, removing thousands of tons of debris from sewers near subway stops and fixing curb heights that contribute to flooding.

“I do think we are in a better position than we’ve been in the past,” said Negret. “We’ve seen tangible improvements in interagency collaboration. … But it will be much more challenging to build the actual infrastructure and figure out which are the agencies responsible for it.”

GRADE: D

Expanding ferries

Never let it be said that Mayor de Blasio was the first mayor to get ocean madness. Rreports from Rudin Center and Mayor Bloomberg agreed that making more use of the city’s waterways could provide an additional way for people to get around if roads were blocked and the subways were disabled. The NYC Ferry system has taken its knocks for low ridership compared to the subsidy that it gets, but Mayor Adams tried to tackle that issue head on by raising the fare.

“The ferry system makes for a great use of our plentiful waterways, and a strong additional mode, especially if subways are offline. It’s improved by the fact that the city recently reconsidered fares to more accurately reflect the cost of operations and the makeup of the customer base,” said the Rudin Center’s Kaufman.

Grade: A

Expanded rail to and from Manhattan

This upgrade only merited a small mention in the Bloomberg post-Sandy report, as it was something that the mayor could only do so much to advance, but Bloomberg did see “Adding System Flexibility” as a place to push for his doomed 7 train extension to New Jersey. On the other hand, NYS2100 spilled plenty of ink on the question of creating better rail service to and from Manhattan: “Two project options, if realized, would expand rail access and connectivity and provide a new layer of redundancy to the regional transportation network.”

Today, those “project options” — the Metro-North expansion to Penn Station known as Penn Access and the cross-Hudson tunnel repair and construction project known as the Gateway project — are at least in the works. The completion date for Penn Access, which will create four new Metro-North stations in the East Bronx for service that connects to Penn Station — has slipped from 2025 to 2027, but that’s nothing compared to the purgatorial grip that transit demons have had on the Gateway project.

Leaving aside the pre-history of Gateway, when it was called “Access to the Region’s Core,” Amtrak and New Jersey Transit have held their breath and for 10 years that the only two tunnels connecting New York and New Jersey would last long enough after their Sandy inundation to be replaced by Gateway. Andrew Cuomo and Chris Christie spent the post-Sandy run of their respective governorships haggling over how their states and the federal government would split a $20-billion price tag for repairs to the existing tunnels and build a pair of new tunnels to double capacity.

By the time everyone got on the same page, the accepted cost was $13 billion, but Donald Trump was president, and the game show host’s wrath against his home city presented itself in the form of slowing down final approvals and federal money for the project.

With federal support questionable, Cuomo began to turn against Gateway, demanding the repairs get done in a similar manner to the way the less-intrusive L train tunnel repairs were done. Fortunately, Trump lost an election and Cuomo resigned in disgrace, allowing New York and New Jersey governors Kathy Hochul and Phil Murphy to limp into a funding agreement and a possible start of construction on the pair of new tunnels sometime in 2023.

The price tag is now $16.1 billion and the completion date is now 2035. Expensive, catastrophically managed across multiple levels of government and paralyzed by bureaucratic disorganization, Gateway is a true testament to our ability to punt on the most pressing issues in response to climate change.

GRADE: F