Civil Rights Group Calls on High Court to Protect Cyclists’ Constitutional Rights

In 2014, police pulled over a man they described as Hispanic riding a beach cruiser bicycle in the Far Rockaway neighborhood of Queens after allegedly spotting something “bulky” in his pants. It was a gun. He was arrested and sentenced to two years behind bars.

Eight years later, the case is now before the highest court in New York because legal experts argue that his Fourth Amendment right that protects against unreasonable search and seizure was violated — that the unconstitutional search would not have happened had he been in a car and not atop a bicycle.

In a new brief filed today at the state’s Court of Appeals, the New York Civil Liberties Union is demanding that cops and courts treat people on bicycles the same as people in cars when it comes to search and seizure — a legal argument that also connects to the disparate criminalization of Black and Brown New Yorkers who get around by bike.

“This determination will have serious ramifications for the millions of Black and Brown New Yorkers who already bear the brunt of stark racial disparities in the policing of bicyclists,” reads the brief’s preliminary statement submitted by New York Civil Liberties Union, alongside Colored Girls Bike Too, Transportation Alternatives, Equitable Cities, and GObike Buffalo.

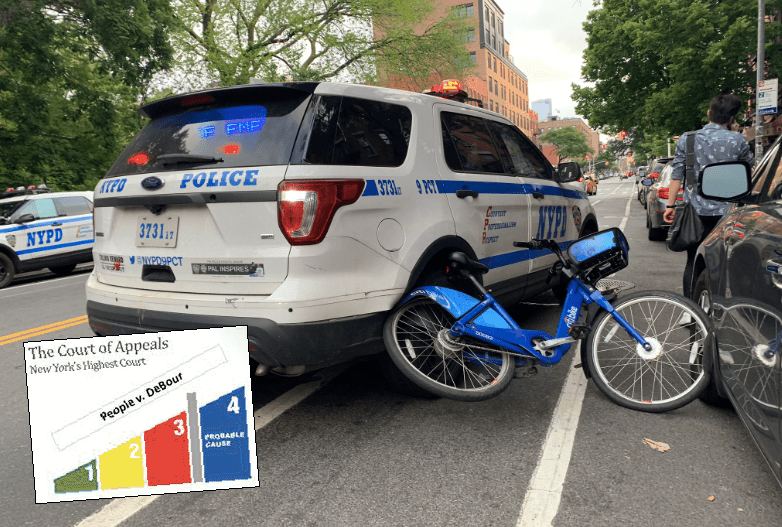

The case in question involves the search and arrest of Lance Rodriguez, but its roots are buried in legal jargon dating back to the landmark New York case, People v DeBour, which established the framework under which police can stop people on the street.

In plain English, there are four levels of a proper DeBour search:

- The first, the least intrusive, typically applies to pedestrians. Police officers only need what’s called “Objective Credible Reason” before they can demand a person’s identification and ask non-accusatory questions. In a first-level search, a person has the right to refuse to answer and can leave.

- A second level DeBour search requires that cops only have “founded suspicion” of criminal activity, such as direct observation or even hearsay. The type of questions cops can ask is limited, and the person is still free to go. Rodriguez, spotted with a bulge in his pants, was stopped using this level of search.

- Such a search can easily escalate to the third, which is considered a seizure and requires a higher standard of reasonable suspicion that the person committed a crime. The person is not free to leave and is subject to a “very intrusive” investigation, according to Lambright.

- The fourth level is an arrest, which requires probable cause.

The courts have long held that cops must apply the third level of DeBour to stopping people in motor vehicles, a holding based on the logic that stopping a person in a car is such a “restriction of the liberty of an individual” that it should be considered a seizure. But the same theory doesn’t apply to cyclists, said NYCLU senior attorney Daniel Lambright.

Had Rodriguez been driving a car that day eight years ago, he likely would not have been stopped.

“A bulge while he was in the driver seat, in itself, would not be enough to pull him over,” said Lambright. “So we’re saying bikes should also be in the same level three.”

The lower constitutional standard for police to pull over and stop people on bicycles permits the police to disproportionately criminalize New Yorkers of color yet again and dissuade these communities from reaping the environmental and health benefits of cycling, the brief suggests.

“What we’re asking of the court is to recognize the disparity in policing we’ve seen and say that cyclists deserve the same rights, at least to be free from unreasonable search and seizure,” said Lambright. “Concerns about discriminatory practices of bicyclists dissuade people of color from engaging in biking, as the city, state, and everybody seem to put a lot of effort into moving people by bikes given the environmental health benefits. But fear of being discriminatorily policed is a major kind of inhibition to getting low-income and communities of color into biking.”

Rodriguez’s case raises multiple issues of law and order. On Dec. 13, 2014 at about 10:40 p.m., 101st Precinct Police Officer Richard Schell was on patrol in an unmarked cop car when, he said, he spotted Rodriguez riding his bike “recklessly,” “with one hand on the handlebar, while the other was holding onto a bulky object on his waistband.” Rodriguez, who was 20 years old at the time, denies he was riding recklessly. He says he was just listening to music.

“It was just me riding my bike. I had my phone listening to music,” Rodriguez said, according to his 2015 testimony during his criminal court case.

Schell says he caught up with Rodriguez, on his beach cruiser bicycle, on Beach 25th Street near Camp Road, and yelled, “Hold up, police.” Rodriguez continued pedaling, Schell said, but he trailed him, repeating his request to stop.

Rodriguez stopped and the officer asked if he “had anything on him.” Rodriguez replied that he had a gun in his waistband. The cops frisked him, recovering a loaded firearm, according to court documents.

Rodriguez was charged with criminal possession of a weapon in the second degree. At trial, Rodriguez’s attorneys argued that the evidence should be tossed because the stop was unlawful. After the court disagreed, Rodriguez pleaded guilty. And after the appeals court upheld the conviction, Rodriguez, with the help of the NYCLU and several transportation advocacy organizations, took his case to the highest court in New York.

Legal experts fear that the court adopting a lower constitutional standard for bicycle stops will give officers even more ability to target and harass Black and Brown people — often dangerous encounters that can lead to police brutality or even death.

The city’s long, shameful history of cops targeting people of color, particularly young Black men, is evidence of that, said Lambright, referring to the NYPD’s controversial practice of stop-and-frisk. As is the data showing who gets a ticket for biking on the sidewalk. In 2018 and 2019, of the 440 tickets issued to bikers for the low-level offense, 374 of those where race was listed — or 86.4 percent — went to Black and Hispanic New Yorkers. During the same 24 months, police issued white cyclists just 39 tickets for riding on the sidewalk — only 9 percent of the total number of tickets where race was indicated, according to Streetsblog’s reporting, which was cited in the brief.

“So this is an added reason as to why we are concerned that a lower standard ability to stop people opens the door for similar types of practices for Black and Brown bikers, essentially a stop-and-frisk for Black bikers,” he said.

Oral arguments are scheduled for Nov. 16. The court will rule after that.