Why the Rent Is Too Damn High: The Suburbs Aren’t Growing

Long Island and Westchester build housing at some of the lowest rates of any suburban area in the country, fueling high rents and home prices across the region.

This article first appeared in New York Focus, an investigative news site on New York politics. Sign up for its newsletter here.

New York City builds less housing per capita than almost any major city in the U.S., one reason it boasts the country’s highest rents. Like other cities, it relies on its suburbs to ease the strain on its housing market.

But when it comes to construction, the suburbs on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley are even less active than the city: They build new housing at some of the lowest rates of any suburban region in the country, trailing the city’s other suburbs in Connecticut and New Jersey as well as the suburbs of Washington, DC, San Francisco, and Boston.

“It’s not just that the New York suburbs are building less than the city. They’re building less than any suburbs on the East Coast, less than the suburbs in California, and that’s before you even get to Texas or Georgia,” said Noah Kazis, a University of Michigan Law School professor and the author of a Furman Center report on housing in New York’s suburbs.

From 2010 to 2021, the New York suburbs issued 70,000 housing permits, or 13 for every 1,000 residents — about half the rate of New York City, and just a third that of the New Jersey suburbs.

“New Jersey has sort of been the relief valve for the region,” said Sean Campion, a housing researcher at the fiscally conservative Citizens Budget Commission, noting that without that state’s relatively high rate of construction, housing costs in New York would likely be even higher.

There is broad consensus among researchers that building more houses and apartments reduces or stabilizes housing costs and bolsters regional economies. One estimate puts the New York metro area’s housing shortage at 340,000 units.

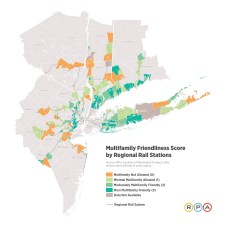

And with the most extensive public transportation system in the country, New York suburbs are well-positioned to provide lower-cost, roomier living options that allow people to easily commute to jobs in the metropolis. But when the Regional Plan Association examined land use regulations in areas with easy access to transit and sewage infrastructure, it found that more than half prohibit all but the lowest-density multi-family housing, and a quarter prohibit any multi-family housing at all.

“It’s really hard to justify that the New York City region, with a booming economy, terrific public services, and best-in-the-nation public transportation, should be the most exclusionary housing region in the country,” Kazis said.

When housing is scarce, people are pushed out. “A lot of people I know are leaving for Austin, Texas, and Florida,” said Hunter Gross, a 26-year-old Long Island resident and president of the Huntington Township Housing Coalition, an organization that supports affordable housing in the Suffolk County town. “I also have a lot of friends who are still living at home.”

As Suffolk County’s home prices have risen to historic highs, it has remained one of the state’s most unfriendly counties for new housing. It issued just nine housing permits per 1,000 residents from 2010 to 2021. Huntington’s population has stayed essentially flat at just over 200,000 people in the last decade, despite having a land area larger than Brooklyn, which has over ten times Huntington’s population.

Building more housing wouldn’t require suburban areas to become second Brooklyns, though.

“Nobody is talking about creating a Co-op City in Westchester,” said Michael Romita, president and CEO of the Westchester Business Association, referring to the 15,000-unit affordable tower complex in the Bronx. “But you need to have some sections of these communities where there’s multi-family housing.”

In addition to an overall housing shortage, New York suburbs also face a severe shortage of affordable housing. Across the metropolitan area, including in New York City, there was a need for more than 770,000 new affordable rentals in 2019, the National Low Income Housing Coalition estimated.

A 2019 report estimated that Westchester County alone needs over 11,000 new affordable housing units, based on rates of homelessness, overcrowding, and affordable housing applications. That’s three-quarters as many as the total number of units it permitted from 2010 to 2021, only a fraction of which were affordable.

‘Far Outpacing New York’

Why aren’t New York’s suburbs building housing?

First of all, because they don’t have to.

New York is unique among large, liberal states in that it gives municipal governments total leeway over what kind of housing they choose to allow or prohibit. Towns use this power to restrict new construction in numerous ways. Some allow only single-family housing in the vast majority of their land area, impose height limits, or only allow developers to build on small parts of their lots. In extreme cases, local governments can entirely ban new housing.

Virtually all of New York’s peers try to prevent local governments from blocking new housing. California and Oregon require towns and cities to plan housing around expected population growth. New Jersey’s Supreme Court has required each municipality to develop a plan to build affordable housing, which must be approved by state courts. Pennsylvania requires local governments to allow some amount of multi-unit housing. In 2019, Oregon banned all but the smallest towns from creating zones reserved for single-family housing.

New York employs none of these measures.

How much housing is your town building? Permits 2010-2021

That seemed like it might change earlier this year, when for the first time in decades, a New York governor proposed limits on local governments’ ability to restrict new housing. Measures included in Gov. Hochul’s January draft budget would have required local governments to allow property owners to build at least two housing units on most properties, and would have prevented localities from banning multi-family buildings within a half-mile of mass transit.

But opposition from local governments and then-candidate for governor Tom Suozzi was intense and immediate. Suozzi repeatedly slammed the proposals at campaign events, calling them a “radical” attempt to “erode the authority of local governments.”

Numerous suburban mayors, county legislators, supervisors, and other electeds joined Suozzi in publicly opposing the measures. Hochul, facing a competitive primary against Suozzi for the Democratic nomination, shelved the proposals about a month after releasing them, effectively ending any chance for statewide zoning reform in 2022.

Local Opposition

Since so many suburban towns employ restrictive zoning, developers who want to build multi-unit housing generally need to get the local town board to agree to a zoning change. The process offers ample opportunities for local residents and groups to mobilize against new development, and often to kill projects outright.

Tim Foley, CEO of the trade group Building and Realty Association of Westchester, described one attempt last year to tear down an office building in White Plains, Westchester, and build 360 apartments in its place. The proposal was rejected by the town council after fierce opposition from five neighborhood homeowners’ associations, who worried that it could add traffic to their neighborhoods.

“That is a story that happens all over,” Foley said.

Even projects that are eventually approved often require years of negotiation with local governments over the number of units, the amount of parking, connection to local infrastructure, the building’s cosmetic appearance, and other features. Navigating this process requires extensive work from teams of lawyers, engineers, architects, and other professionals, delaying construction and increasing costs.

“Every time a developer needs to come back to a town board with a modification of your plan, designing that modification costs money,” Foley said. “That means that a lot more has to be devoted to that process that could otherwise be devoted to actually building more housing.”

The length and expense of rezoning battles incentivize developers to build high-end single-family housing, since that doesn’t require zoning changes, Foley added.

“The stuff that people know can get built tends to be single-family homes, including McMansions,” he said.

Affordable housing is particularly vulnerable to local opposition, since affordable developers generally want to build apartment complexes that are often prohibited by local zoning. Neighborhood opposition can be fierce. At a public hearing last month on a proposed 60-apartment affordable development in Southampton, Suffolk County, ten local residents testified against the project. Zero spoke in favor.

“When we heard about what they were doing about this affordable home, and how they want to come through our neighborhood, it disgusted me,” lifelong Southampton resident Shonda Campbell said at the hearing.

“We do not want any traffic from any kind of affordable homes coming through our neighborhood,” she added, to applause from attendees.

The fear of local opposition to affordable development can dissuade developers from making proposals at all. “There’s a lot of places in Westchester where you wouldn’t even try building affordable,” said Richard Nightingale, president and CEO of Westhab, a Westchester-based affordable housing developer. “You’re not going to spend the money on lawyers and architects to even draw up a plan because it would just be impossible.”

Even small market-rate apartment buildings, which are still generally cheaper than single-family homes, are unwelcome in many parts of the suburbs. “I don’t think that that’s something that the townspeople would really care for. I think they like single-family,” said Warren Lucas, supervisor of the town of North Salem in northern Westchester. “There’s nobody that I know of that would build it.”

Albany in Action?

With most of New York’s local suburban governments firmly in opposition, many housing advocates are hoping for relief from Albany.

“There’s a high payoff rate for passing statewide policies versus taking smaller steps such as neighborhood rezonings,” said Logan Phares, political director of the pro-housing group Open New York. “The state holds a lot of power to create new homes.”

The top priorities of many advocates for more housing are the same policies that were pulled from Hochul’s budget proposal earlier this year: requiring localities to allow accessory dwelling units and relatively dense housing near public transit.

Tenant groups, meanwhile, are lukewarm on the measures.

“Those are fine proposals that will potentially help New Yorkers struggling to find housing but they’re not the game changing things that we focus on,” said Cea Weaver, campaign coordinator of the tenant organizing group Housing Justice for All.

A Hochul spokesperson declined to say whether she will reintroduce the proposals in her next budget proposal. If she does, they are likely to meet the same strong local opposition as when they debuted earlier this year.

“We just don’t want things that say, ‘Okay, the state controls local zoning,’” said Lucas, who is also an officer of the Westchester Municipal Officials Association. “Something from the state that opposes home rule is not something any of us will ever agree with.”

Overcoming that opposition is a top priority for people like Gross, the Suffolk County affordable housing activist, who currently lives with his aunt in Huntington but is looking for his own rental apartment. He hopes to stay in Huntington, where he grew up, but worries that he won’t be able to.

“It’d be great to raise a family and to live out here, but the current regulations and the lack of affordable housing is really not going to make it possible,” he said.