BPM? BTA? Whatever Model You Use, Congestion Pricing is Good for the Region

Congestion pricing is a win for the New York City region — and, in fact, the only question surrounding the proposed central business district tolling is just how big a win.

When the MTA released its long-awaited environmental assessment in August, it revealed seven scenarios to model what would happen with various combinations of toll prices, credits and exemptions. Under any of the scenarios, vehicle miles traveled were predicted to drop by as much as 9 percent inside the Manhattan central business district, but VMT was predicted to barely budge across the rest of the city and region. Every modeled scenario in the EA also predicted a small net increase of truck trips on the Cross Bronx Expressway.

And that’s a miscalculation for the MTA — both literally and politically — according to longtime congestion pricing expert Charles Komanoff, who says that the agency’s reliance on a clunky traffic model failed to include what he calculates will be far broader benefits for the region.

In a follow up piece to his first critique of the MTA’s congestion pricing environmental assessment, Komanoff wrote that the MTA’s analysis vastly underestimated the reduction in vehicle miles traveled outside Manhattan’s CBD at just a 0.4-percent cut. Komanoff’s own internationally respected model, however, predicts that a combination of a reduction in trips both into and through the CBD would lead to a 2-percent reduction in VMT or almost two million fewer miles traveled in the entire region every single day.

“The contrast is so stark that it should dispel the notion that only residents of Manhattan stand to receive congestion pricing’s bounty of lesser traffic,” Komanoff wrote last week for Gotham Gazette.

The idea that the MTA’s modeling has hurt the cause of congestion pricing isn’t because the agency screwed up but merely a result of the MTA and its consultants being forced to rely on a model that’s trying to do too much for too wide a region.

Where Komanoff’s BTA model estimates “changes in auto tolls, transit fares and other variables on traffic levels, travel speeds, time spent traveling, agency revenues, emissions and other vehicle ‘externalities,'” the MTA used a federally recognized planning document known as the New York Best Practice Model, which “incorporates transportation behavior and relationships with an extensive set of data that includes a major travel survey of households in the region, land-use inventories, socioeconomic data, traffic and transit counts, and travel times” to predict travel patterns in response to various policy changes and infrastructure projects.

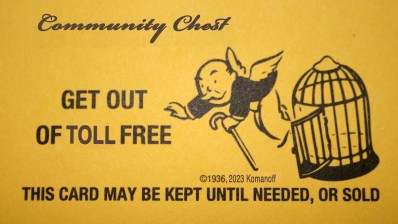

Put more simply, the BTA is a model concerned with how drivers will behave if a congestion pricing toll is put in place in New York City, and its cost-benefit analysis include such seemingly unrelated affects as the toll itself or the “cost” of air pollution on regional residents. The BPM, on the other hand, is used to forecast policy impacts down to individual street or highway stretches.

While the inner workings of the BPM aren’t a reason to discount it, other traffic experts say there are reasons to look at other models.

“The BPM is a bunch of eggheads who are taking data from lots of different sources, a ton of data, too much data in this particular case, to try to model what everybody does within a region, so it’s very cumbersome,” said “Gridlock” Sam Schwartz, a longtime congestion pricing proponent and the city’s previous Traffic Commissioner. “It’s kind of like a Rube Goldberg machine, whereas [the BTA] used the savviness of what really happened each time there was a toll and focuses more on the river crossings and the VMT that is contributed by the various modes. So I would say Charlie’s is more surgical, where the BPM is a blunt instrument.”

All of which is to say that the BPM isn’t wrong. But it does wind up giving conservative estimates.

“It really is an unlikely thing that [the MTA] messed up; it is that the model is really cumbersome. And what it tries to do is figure out what 30 million people in the region would do under various circumstances, so there’s some imprecision,” added Schwartz.

The BPM is a federally recognized traffic model, which is why the MTA used it, and why Schwartz said that he’s OK with the agency relying on it for this initial projection. But he also encouraged the Traffic Mobility Review Board, the six-person body actually charged with coming up with the congestion pricing toll price and exemptions to it, to make use of Komanoff’s model when the board eventually starts meeting and developing its toll policy recommendations to the MTA.

“We’ve got a document that had to be done according to worst-case analysis. The Transit Mobility Review Board should say, ‘Hey, let’s call Charlie in and see, what if we change this by another dollar or $2? Or $5? What if we don’t charge this? What if we give this credit? What happens?’ The [BPM] model cannot do that,” he said.

It’s also important to understand traffic models aren’t made by soothsayers with the gift of perfect foresight. They are used to study different scenarios, but they remain merely data-based estimates, not locked-in guarantees of the future.

“Models give us insights, they don’t give us answers,” as Regional Plan Association Director of Research Strategy Rachel Weinberger put it.

And for the BPM, its insights were the ones that the federal government was looking for. And the good news is that both the BPM and BTA find benefits for the entire region.

“The purpose is to understand at the regional level what is happening with regional air quality, and this is showing at the regional level, lower VMT and better air quality. So in some ways, that really is the tool that we’ve got,” said Weinberger. “Sometimes you need a framing hammer, but all you have is a ball peen hammer, but you still have got to get that nail in the wall, right? So you have to be creative in how you use the tool that you have. For the purposes of the federal government, the model has done what it needs to do.”

MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber said as much when asked whether the MTA’s numbers were too pessimistic about congestion pricing.

“I respect the people who were who expressed that point of view and the analytics that they’ve done,” Lieber said on Thursday. “The studies that we have done were developed with the supervision and approval of the federal regulators. The key was they were establishing the analytics, data modeling, the traffic modeling, the air quality modeling. … So we were following the the rules of the road that they set out. I can’t speak to specifics other than saying that our approach was developed with the supervision of the feds, so it was meant to first and foremost comply with whatever they demanded.”

Weinberger also warned that the focus on which model gets you better results could threaten to overtake actual findings in the environmental assessment that the MTA and New York City and State have to plan for, whether or not they’re guaranteed to happen.

“The other part of the conversation that’s not getting enough air time is not, ‘Oh, there’s going to be 700 more trucks going across the Bronx, and that’s not OK,’ (it’s not), but ‘What can we do to offset the environmental harm to that community by this potential addition?’ This is not, ‘The model says congestion pricing is going to do this.’ The model says, ‘One possible outcome is this.’ And good that we know that now. Because now we can get out there and do something about it. It’s an environmental assessment. We now know the range of potential environmental harms. What can we do to address them?” she said.

And, ultimately, because a model can only go so far, sometimes a state or city has to look at what’s happened in the real world for a model. In the case of congestion pricing, New York wouldn’t be taking a leap of faith, because it’s a policy that has been implemented successfully in cities around the world.

“We think that’s a better model. We think London, Stockholm, Singapore, Gothenburg, Milan, there’s definitely on ground examples of success. And I cannot think of any example where it’s been pulled due to failure,” said Weinberger.