Chastened MTA Tries to Redesign the Queens Bus Network, Again

Second time’s the charm?

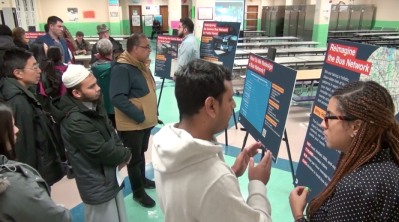

The MTA rolled out a second attempt at Queens bus redesign on Tuesday, two years after lighting a fire under Queens residents (in a bad way) with an attempt at remaking the century-old system maps.

Agency leadership was keen on making two points about the redesign on Tuesday. First, separating the new attempt from the 2020 version that was derailed by opposition from the entire Queens City Council delegation and then by the coronavirus pandemic that made it impossible to hold in-person feedback sessions, and, second, emphasizing that the original redesign was merely a draft that was subject to changes based on what the agency heard at feedback sessions.

“We know we need to get it right this time,” said MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber. “The first draft plan, which came out in 2019, didn’t get all that well received, to say the least. So during Covid, our teams went back to the drawing board armed with the more than 11,000 comments that we received from customers and came up with a new draft, which I emphasize is a draft subject to change based on the dialogue that is about to unfold.”

The increased frequency of service on 108th Street on the Q23 will be a gamechanger. Service on weekends should still be upped further. pic.twitter.com/E6qgf6PZCO

— Union Tpke (@Union_Tpke) March 30, 2022

Like routes across the city, Queens buses have suffered ridership and speed losses that the MTA hopes it can reverse with the redesign. Weekday peak hour local and limited buses traveled at 8.4 miles per hour in January 2015, and dropped to 8.2 miles per hour as of February 2022. The percentage of customers who finish their trips within five minutes of its scheduled time has stubbornly stayed at under 75 percent, with 74 percent of riders getting timely rides in August 2017 and 74.4 percent in February 2022. As a result, ridership has dropped from 728,782 riders in 2014 to 666,070 in 2019. (And those are pre-pandemic numbers.)

The draft plan differs from its predecessor in both the presentation of the new routes and the number of routes that will still exist after the redesign is done. Where the last plan identified new routes with a “QT” moniker, the new draft simply keeps the old Q[NUMBER] designation to cut down on confusion. And where the first redesign cut the number of Queens bus routes from 82 to 77, a move that drew criticism as a stealth service cut under the guise of simplifying the network, the new draft plan proposes that Queens winds up with 85 routes, including 20 all new routes and five routes that are combinations of two or more existing routes.

Here’s a better take than “lose”: https://t.co/Q7UrnzonrG https://t.co/0hIPBKrVFn pic.twitter.com/koitrcgNUj

— Jon Orcutt (@jonorcutt) March 30, 2022

Crucially, MTA leadership has said that the redesign is not revenue-neutral. The MTA didn’t reveal how much more money will be spent on the bus system after the redesign is implemented, but Lieber explicitly said that the agency had abandoned the idea of a revenue-neutral design.

“There’s a vision of new routes that stop a little less, but connect to major intermodal connections,” he told reporters on Tuesday. “So maybe there’s going to be continue to be a lot of local bus service with a lot of stops, but there will also be some buses that go much faster and much more directly to connect, for example, to Jamaica station. We’re trying to do both, which is one of the reasons that we are not putting a cap on how much this plan can cost to implement.”

Despite the somewhat chastened tone after the first attempt to remake the borough’s extensive and sprawling bus network, the draft redesign shares elements with the first draft, particularly in the way that bus planners went about trying to make the new map. Once again, the bus local network is broken into four types of bus routes that seek to accomplish one specific goal: get people from outlying areas to subways, lower demand routes that serve and connect neighborhoods, high-demand limited service that relies on spacing stops one-quarter or one-third of a mile from each other, and SBS routes with stops spaced at least one-third of a mile away from each other that emphasize connecting what the MTA calls “key destinations.”

MTA planners emphasized the Limited and SBS routes as the workhorses of the redesign, with promises that they would run with headways of 10 minutes or less between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m. on weekdays, and route designs that connected to places like employment centers like East New York, Canarsie, Downtown Brooklyn, LaGuardia and JFK Airports, and the Jamaica and Flushing transit corridors.

And similar to the first draft plan, the new draft includes the 49 “primary” or “secondary” bus priority corridors that the Department of Transportation identified along with the MTA. On those corridors, which were identified based on factors like ridership demand, bus speeds, equity considerations and the ability for streets to handle improvements, the agencies will focus on studying and implementing transit priority projects like busways and bus lanes, or physical bus stop upgrades. (Studying?)

Planners are also still counting on eliminating a number of bus stops in order to speed up buses on all of the routes. The first offer from the agency is to extend the distance between stops from the current average of 818 feet to 1,198 feet away, which will consolidate hundreds and hundreds of stops. Although the process of spacing out bus stops is a contentious one, the agency argued that each removed bus stop could subtract 20 seconds from a bus journey, something that adds up when removing stops. Agency officials said that removing stops is one element of the effort to speed up buses, but the redesign was not guided by how many stops were removed but what type of stops got the axe.

“When it comes to the network redesign, it’s not about removing bus stops,” said New York City Transit Interim President Craig Cipriano. “It’s about how many riders do we anticipate using a bus stop, what’s the land use around the bus stop, what are the intermodal connections? There’s no hard and fast goal. We’re trying to speed up our bus system, and one aspect of speeding it up is the amount of time that a bus spends in a bus stop. So we balance out all those, put those assumptions down and we make recommendations, and then we have feedback from our customers and other stakeholders.”

With that in mind, agency planners said that they revisited the way that the old draft treated subway connections. While the idea of getting bus riders to the subway was seen as a laudable goal of the first redesign effort, critics said that the plan didn’t consider the quality of the subway connections buses brought people to. The second draft of the redesign therefore, was guided by whether buses connected riders to subway stations that are already accessible for disabled riders or are planned for accessibility upgrades in the 2020-2024 capital plan.

The new draft plan was able to win over at least one critic of the previous plan. Queens Borough President Donovan Richards, who called the first proposed redesign a “Jedi mind trick” that substituted speed for service, said that he was ready to hear community feedback, but that he was ready to sell his constituents on the new draft.

“When you look at what the MTA has come back with, at least what I have seen thus far, you can tell that they definitely listened to communities,” Richards said. “So, yeah, I’m here as a salesperson to say, ‘Let’s get this done.’ Of course, there’s a lot more community input, but there’s no such thing as a perfect plan and we should not let perfect be the enemy of good as well.”

The Bus Turnaround Coalition, which consists of several transit advocacy groups including Riders Alliance, also seems supportive at first blush:

“Queens bus riders badly need better service and faster trips,” Riders Alliance Senior Organizer Jolyse Race said. “We’re encouraged by the innovations and new routes in today’s proposal. The MTA should use the redesign to narrow the racial gap in access to opportunities, which currently favors white New Yorkers over Black and brown New Yorkers. We urge the MTA to listen closely to riders’ needs as the draft redesign becomes final.

The group also called on Gov. Hochul better fund the MTA to create transit service that “reaches every neighborhood of the city’s biggest borough.”

Unlike the original draft, which had scheduled dates for a final plan release and implementation of the redesign, the second attempt is open ended for both a final plan and an implementation date. Starting on April 18 and running through June 2, the MTA will hold feedback meetings with each of 14 community boards in Queens, but feedback can also given on the bus redesign website and on interactive maps for both the local and express services.