IT’S OVER: State’s Highest Court Sets Aside Last Challenges to City’s ‘Right of Way’ Law

It turns out it is a crime to drive with negligence and then hit someone with your car.

The state’s highest court unanimously upheld the city’s “Right-of-Way” law, a 2014 provision that made it a misdemeanor for a driver to “fail to exercise due care” and then injure a pedestrian or cyclist who has the right of way. The ruling by the Court of Appeals aside the final plea from drivers in two horrific and high-profile cases who argued that mere negligence and carelessness should not be considered a criminal offense, even if it leads to the maiming or death of a pedestrian or cyclist.

Both drivers had argued in lower courts that they could not possibly be guilty of a criminal offense because to commit a crime, a guilty person must have mens rea, a Latin term that speaks to a suspect’s state of mind at the moment of the crime.

And, indeed, in a criminal case, the burden of proof is on prosecutors to show that the alleged perpetrator knew that his actions would violate the law — and acted in full knowledge of same. In essence, both drivers were arguing that failure-to-yield can only be a “crime” if the suspect is acting “intentionally,” “knowingly,” recklessly,” and/or with “criminal negligence,” which are the four “culpable mental states” that are strictly defined in the state’s penal law.

But Justice Michael Garcia, writing for the full court, disagreed.

“The Right of Way Law is not silent on mens rea,” he wrote. “Instead, it specifies a mens rea of ordinary negligence.” Besides, he added, “Our legislature has also enacted [many] laws that impose criminal liability based on ordinary negligence.”

The case got to the Court of Appeals thanks to lower court appeals by two killer drivers:

- Carlos Torres, a truck driver who pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor failure-to-yield crime after killing pedestrian Elise Lachowyn near the Javits Center in 2016. Later, though, Torres appealed, citing the mens rea argument. But the appeals court rejected his argument in 2019.

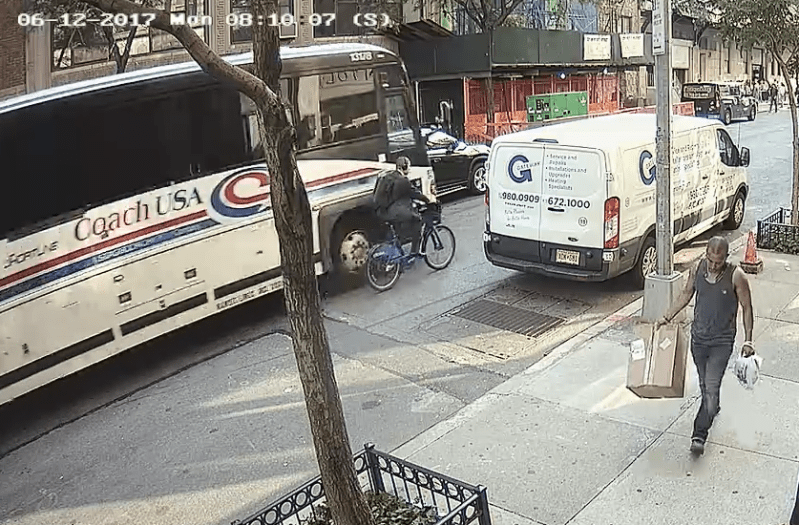

- Bus driver Dave Lewis also appealed his Right-of-Way conviction for failing to yield to, and then killing, Citi Bike rider Dan Hanegby in 2017, citing a similar argument as Torres. Lewis’s first appeal was also rejected by the same appeals court in 2019.

But both appeals were set aside handily by the unanimous decision, which also set aside a side argument that New York City does not have the legal right to criminalize an offense that is not considered criminal under state vehicular law.

The notion that a city would pass a law beyond the scope of a state law is known as “preemption” — but it is usually invoked to challenge a city law that is in conflict with a state law. No such conflict exists in this case.

“We conclude that the Right of Way Law does not run afoul of the preemption doctrine,” Garcia’s ruling read. “[State vehicle law] also authorizes New York City to pass laws relating to, among other things, ‘traffic on or pedestrian use of any highway,’ including ‘right of way of vehicles and pedestrians.’

“The Right of Way Law falls within this delegation of authority, defeating defendants’ [other] preemption claim,” he concluded.

Lawyer Steve Vaccaro, who represents cycling and pedestrian victims and was involved in the Hanegby case, felt vindicated.

“It’s what we were saying: Plain old negligence is adequate to create a criminal offense, it’s an adequate mens rea,” he said. “And I also said all along that there is a provision in the state law that the city has the authority to legislate in the area of right of way. It’s wonderful. And it’s unanimous!”

Vaccaro predicted that city lawmakers will now be emboldened to create new laws.

“This decision says the city is allowed to govern its own streets,” he said. “This decision is a green light from the Court of Appeals to the city to experiment new ways to save lives on the streets of New York.”

And retiring Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance Jr. was also pleased by the ruling — especially given his office’s prosecution of both Lewis and Torres at trial and at the appeals levels. He credited his office.

“I’m grateful to our prosecutors who have fought since day one to defend the constitutionality of this critical vehicular accountability legislation, culminating in this unanimous victory in New York’s highest court,” Vance said in a statement to Streetsblog. “We will continue to aggressively enforce this statute.”

The clarity from the High Court could not come at a better time, given the increasing number of deaths on New York City roadways this year, which may be partially due to a 50-percent decline in the number of moving violations tickets written by NYPD officers.

Tuesday’s ruling did not come without some concern for street safety activists, in the form of a history lesson from concurring Justice Rowan Wilson. After first explaining that he joined the majority decision “in full,” he then revealed the tortured history of state and city efforts to rein in reckless drivers, which began by creating “traffic violation” summonses so that drivers would not constantly be charged with criminal offenses for

“The legislative history,” Justice Wilson wrote, “suggests that a concern about over-criminalizing traffic violations motivated the Legislature to adopt” traffic summonses instead of classifying all injury-causing crashes as criminal cases. The “principal object” of then-Assembly Member James Robinson’s 1934 bill creating traffic summonses was “the removal of criminal stigma which now attaches to all minor traffic violations.”

In those days, 75 percent of all misdemeanor cases were traffic cases, so members of the public would indeed have quickly earned criminal records, even though they were “not criminals in any sense,” in the words of a top judge at the time.

But, based on the High Court’s ruling, they are, in fact, criminals in one sense: failing to yield the right of way in a negligent manner that leads to an injury is, finally, a crime.