A New York original and unsung genius who many thought was a crank, he discovered a long-forgotten subway tunnel under Atlantic Avenue.

Some said that Robert Diamond was a genius; others said that he was paranoid; all agreed he had not mastered the art of social fakery.

But he played by the rules (that constantly changed) and in the end he lost everything. He was screwed.

So were New Yorkers, who lost Bob Diamond, a true Gotham original who was a hot (and always controversial) figure in Brooklyn, who died on Aug, 21 at the age of 62.

In 1980, Diamond, a self-styled urban archeologist and Brooklyn’s own Indiana Jones, re-discovered a long-forgotten 19th-century train tunnel beneath Atlantic Avenue, between Columbia Street and Boerum Place, which was built by the Long Island Railroad in 1844 and sealed off in 1861. It was the first rail link between New York and Boston and, according to the Guinness Book, the oldest subway on the planet.

Despite endless bureaucratic roadblocks, Diamond spent more than a year poring over archival maps and articles and then battling municipal powers to gain entrance into a tunnel that the authorities said didn’t exist and, if it did, it surely wasn’t where he said it would be.

For almost 30 years, the rotund Brooklyn native, who had a deadpan style and spoke in a New Yorkese drone, gave tours of the cavernous tunnel, a surreal experience if ever there was one. When I attended the tour, shortly before the tunnel was shuttered by the city in 2010, the line for the mini-adventure wound around the block.

Clad in sneakers and flashlights in hand, one by one we inched down a vertical ladder beneath a four-and-a-half by three-and-a-half foot rectangle on Atlantic Avenue and Court Street. While it took a few moments to acclimate to the dim light and pervasive creepiness, it was a fascinating and entertaining afternoon as we cautiously moved through the half-mile-long stony tunnel that was about 21 feet wide and 17 feet high.

Part scholar, part standup comic, and a terrific storyteller, Diamond evoked the corrupt politicians and industrial barons of the 1800s and brought to life the tunnel’s folklore: It was home to pirates, bootleggers during Prohibition, German spies in World War II, and five-foot rats in the present.

Diamond also said a 19th-century, wood-burning steam locomotive lay behind the sealed tunnel wall near Hicks Street and Atlantic Avenue and speculated that missing pages of John Wilkes Booth’s diary were hidden there as well. Now housed at Ford’s Theater, the diary is indeed missing many pages, and there’s no shortage of theorizing as to where they may be and what they may contain.

National Geographic got into the picture, and for awhile it looked like a documentary about Diamond and the tunnel was in the works. But then the city Fire Department sealed off the tunnel, alleging that the entire operation was unsafe, despite the fact that Diamond had been running the tours uneventfully for three decades. Diamond was unceremoniously stripped of his livelihood and identity.

Who was Bob Diamond?

I first met Diamond in 2015 in a now defunct Connecticut Muffin in Kensington, his cross-cultural Brooklyn neighborhood. It was beginning to undergo gentrification, but nonetheless brought to mind an earlier era, with its one-story store fronts, six-story brick apartment buildings, and detached, columned homes that were at one time mansions. I was writing a story for a colleague’s blog (which no longer exists).

Disheveled and baggy-eyed, Diamond admitted he couldn’t sleep and when he fell asleep had nightmares. “Only they’re not really nightmares,” he said. “They’re just repeated images of the experiences I’ve had.”

Diamond suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, started each day with Prozac, had gained 150 pounds and lost a mouthful of teeth. (“I’m fat and toothless,” he said.) He was afflicted with debilitating back pain, crippling leg cramps, and red blotchy skin eruptions.

He survived on SSI and lived in his late mother’s tightly packed Flatbush apartment, which was piled high with leather-bound first editions, antiquated maps, frayed and yellowing magazines, and other arcane materials on the history of transportation, secret and powerful fraternities, and occult events. His two roommates included his girlfriend Sharon Rozsay, who paints landscapes (she had created large, site-specific installations) and his silver-haired poodle, Silver, who has since passed.

Diamond evoked a defeated child-man even as he displayed a sly sense of humor and an uncanny mind that accumulated and retained information on an array of topics, including pop-culture trivia and especially chicanery of all kinds. He was a conspiracy theorist, although he was not political and did not vote.

“It’s a shame there aren’t any elected officials with a pulse,” he said.

Diamond believed in the power of visions, dreams, and flights of fancy to warn, guide, and instruct. Coincidence rarely existed for him, and omens were everywhere if you were evolved enough to see them. He alluded to shadow acquaintances who had shadow lives and were often employed by shadow agencies — government and/or private.

Still, there was an element of performance as he reveled in his clairvoyant flashes or disparaged the behind-the-scene (and often unnamed) operators. He was at once wholly serious — usually literal-minded — while paradoxically boasting a keen sense of the absurd and, at moments, a startling self-awareness that surfaced in wonderful non sequiturs: “Will the real Bob Diamond please stand up?” Diamond muttered. “There’s a fine line between genius and thinking aliens live under your bed.”

He believed his own lack of formal credentials — despite being conversant in string theory, quantum mechanics, the Butterfly effect, Higgs Boson, linked equations, and dark energy — had rendered him especially vulnerable. He was an impassioned hobbyist and likened himself to Heinrich Schliemann, who found ancient Troy, or Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon, who dug up the King Tut tomb in the 1920s.

“Someday, someone is going to dig on the Temple Mount, and they’re going to find something and it’s going to be an amateur archeologist who makes the discovery,” he said as he methodically ripped open each of his 20 packets of sugar, dumping their contents into his tall cup of black coffee and taking a disgusted sip. (“It tastes like there’s gristle in it,” he said.)

“I liked this place better when it was The Independent Democrats of Flatbush and the club house for Mel Miller who was the Assembly speaker and then lost his seat when he was convicted of a felony,” he said of the location. “Hey, this is Brooklyn.

“But in those days you could just drop by and talk to someone. One day my mother went in and said, ‘My son found a tunnel, blah, blah, blah, could you help him with the city?’ It was, ‘Yeah, send him over.’ And they called [then-Brooklyn Borough President] Howard Golden, and I got to see him.

“Today, you can’t get through to anybody. I tried six times on de Blasio’s Twitter account, along with his City Hall email. Not a peep. I know if I could have 10 minutes with him I could convince him to open the tunnel and start the light rail in Brooklyn. But there’s no access. It’s like the Kremlin under Stalin.”

Diamond conceded he was still at loose ends since the death of his mother Elsa in 2008. A licensed cosmetologist who had her sights set on an acting career, she was the central figure in his life and they had a stereotypically close Jewish mother-son relationship, although she often blamed him for getting in the way of her show-biz aspirations. “‘I couldha been a contendah,’” Diamond intoned.

“But, she was very good at summing up situations quickly. She’d say, ‘This is how you’re getting screwed.’ But she wouldn’t know how to fix it.” Still, he continued to speak to her — more precisely, her ashes in an urn at home — seeking her advice. “I ask her, ‘What am I supposed to do now? How do I get out of this one?’”

Diamond’s background was a mixed New York bag, a little Damon Runyon, a little Saul Bellow. His Polish-born, Jewish maternal grandmother, who fled to America to escape her molesting stepfather, was married to a Jew, had three daughters, though decades later she claimed that two of them, including her youngest Elsa, were the offspring of an affair she’d had with an Irish-American cop.

Likewise, Elsa was originally married to a Jew, but ultimately left him for a small-time, Italian-American gambler, who was Bob’s father.

“He’d come and go,” Diamond recalled. “He’d come around and we’d all go to Big Daddy’s in Coney Island. Then he and my mother would get into a big fight and he’d disappear. He’d have drunken rages and smash furniture and throw things into the wall, including me.

“He left the house for good when I was in third grade and showed up briefly when I got attention for the tours. That’s when I found out I had two half sisters, both married to gangsters. One of the husbands wouldn’t give me his last name, only wanted to be known as ‘George George.’ My other brother-in-law offered me a high-paying job in waste management and said I wouldn’t have to come to work. I also found out my father was distantly related to Anastasia who headed Murder Inc. and was assassinated in a barber chair. That was a famous scene in ‘The Godfather.’ Hey, you can’t make this stuff up.”

Diamond was an outsider on many fronts. He was ostracized by the Jewish kids for not going to Hebrew school while the Christians wondered aloud why they never saw him in church.

Diamond identified as a Jew and believed in God.

“If you’ve seen a sun rise, how can you not believe in God?” he asked rhetorically. “As for Jesus … My aunt used to say, ‘There probably was a rabbi named Jesus, but we don’t believe he’s God.’ That’s what we don’t know. Maybe if you’re so good and so righteous you become God. Somebody’s got to do it. Not that I know why anyone would want to.”

The search begins

Discovering the Atlantic Avenue Tunnel was almost a fluke spawned in the wake of a crisis. Diamond had received a Kodak scholarship to the Pratt Institute as an engineering student. (In 12th grade, he had won first prize in an alternative-energy-sources competition for designing a solar-cell satellite that converts solar cells into electricity.) But because the school had urged him to apply for the Kodak scholarship — and he nailed it — in his sophomore year he lost his Pratt money and found himself slapped with a huge bill that he could not pay. As he understood it, he’d have to work for Kodak for eight years before returning to school. He was certain that entailed working for the military and he wanted no part of it.

“Hey, I’m an artist,” he said.

Depressed and confused, Diamond came home and turned on a radio show where G.J.A. O’Toole’s latest thriller, “The Cosgrove Report,” was being discussed. The novel explored the idea that, following President Lincoln’s assassination, John Wilkes Booth escaped to Europe but, before he left, he hid pages of his diary in a metal box near a steam locomotive in a long forgotten Brooklyn tunnel. The missing pages supposedly held details of an assassination-plot conspiracy among Southern confederates and their supporters in New York.

Initially, Diamond was far more intrigued by the prospect of a hidden tunnel and steam locomotive than any diary, and contacted O’Toole who, according to Diamond, pretended to have no idea what tunnel he was talking about, insisting the book was a work of fiction. Diamond did not buy that, especially because O’Toole had served as a CIA agent and Diamond suspected his fictions were fronts for the truth.

Diamond headed to the map department at the main library at 42nd Street and spent the next seven months studying dozens of old Brooklyn maps before coming across an 1845 map showing train tracks emerging from the New York Harbor waterfront at Atlantic Avenue and Columbia Street, then disappearing and reappearing at Boerum and Atlantic Avenue.

Other maps confirmed his initial finding. Then, after 1861, the tunnel no longer appeared on the maps. More research led to a 1911 story in the Brooklyn Eagle, reporting that Brooklyn had the world’s oldest subway and that no one had been able to find it, although many had tried, including a team organized by the paper.

Undaunted, Diamond sought out Howard Golden’s head engineer, “who was reading the Racing Form when I arrived,” said Diamond matter-of-factly. “When I asked for the 1868 Nassau Water Commissioner’s map, showing cross-sections of the tunnel, he said, ‘You’re another one looking for the tunnel. I looked for it. It doesn’t exist.’ ”

Finally the head engineer put down the thoroughbred past performances, disappeared into another room and retrieved a huge trunk stuffed with ancient materials, including blueprints of the Atlantic Avenue Tunnel dating back to the 19th century.

Diamond landed an appointment with Golden, who found the idea of a hidden Brooklyn tunnel fascinating and asked the Department of Environmental Protection to remove the manhole lid at Atlantic Avenue and Court Street.

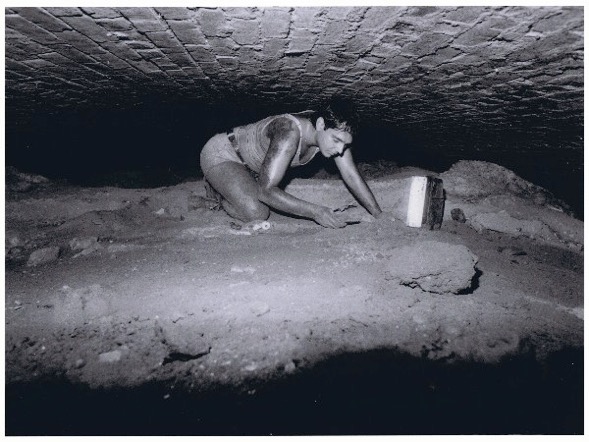

“But when they lifted it up, it looked like any other manhole and didn’t go anywhere,” said Diamond, who dropped down into the hole. “It was dark and only 18 inches high, but I was thin back then and with the help of a hand-held electric lantern, I crawled on the dirt floor for about six feet until I saw an arched ceiling. There it was.”

The DEP didn’t want to continue with the project, arguing there were five-foot rats and poisoned gas in the tunnel, none of which was true, said Diamond. He then contacted Alan Smith, assistant vice president at the Brooklyn Union Gas Company (now called National Grid), whom he knew from his high-school days, when Smith was in charge of the alternative-energy science competition.

Smith was willing to help Diamond, but insisted that he find professional archeologists who would authenticate the project, as proof of validity to the stockholders. Diamond checked out the Yellow Pages, where he came across Professional Archeologists of New York, whom he called and now views as the most ill-fated call of his life. At the time, however, the group seemed enthusiastic, he said.

The tunnel exploration was set for a morning in August 1981, and all agreed to meet at the manhole at 9 a.m. To rev himself up for his adventure, the night before Diamond went to see “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” but in the middle of the night he was abruptly awakened by his frantic mother.

“ ‘Get up,’ she was shouting at me. ‘Why? It’s five in the morning?’ ” Diamond said. “She said, ‘You have to go down there now. Something stinks. It’s all been too easy.’ ”

He got dressed and just as the sky was beginning to lighten, boarded the train at Cortelyou Road and arrived at the manhole at 7 a.m. to discover the archeological team hanging around as the gas-company engineers were sealing the manhole shut.

When Diamond asked what was happening, the engineer told him the PANYC team had written to the gas-company chairman, arguing they didn’t need a stupid kid. “But when they got into the manhole and saw the 18-inch space, they were too scared to continue and told the engineers to weld shut the manhole.”

Diamond demanded that the engineer let him into the manhole and, while four PANYC members stood on the street, Diamond lowered himself into it with an air tank, a gas mask and a walkie-talkie.

“I had a belt around me like a mountain climber and the engineer told me, ‘You got five minutes,’ ” he recalled. “So, I went down into the 18-inch space that must have been a hundred degrees and crawled 70 feet across sharp pebbles to the closed wall. I said to myself, ‘What did Indiana Jones do when he couldn’t find his way into the opening where the ark was?’ He dug by hand and that’s what I did, digging into a pile of dirt, three feet thick. I got through it and saw a door bolted into a concrete wall and cemented over with cobblestones and brick. I pulled out the walkie-talkie, but I couldn’t speak because I was laughing so hard. I found it. These experts couldn’t find anything.”

A few moments later, he was joined by several engineers and the PANYC team, who crawled their way in, and with crowbars in hand, broke off the stones from the doorway, pushing the door open.

“We felt a rush of cold air, though it was pitch black,” said Diamond. “You couldn’t see a damn thing. It was just like ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark,’ except if we shined a light behind the door, we could see a 15-foot drop and on the floor a big wooden plank with nails sticking out. So, we couldn’t just jump in.”

The gas-company engineers were ready to call it quits because they did not have a sufficiently tall ladder. But Diamond insisted that he be allowed to climb out of the manhole and go to Bruno’s, a local hardware store, to purchase a chain ladder.

“ ‘You got $20? Give me $20,’ ” he enjoyed re-playing the moment. “They give me $20 and I go up and get the ladder. It didn’t occur to anyone else to buy a chain ladder.”

Triumphant with his purchase, he descended yet again and set the chain ladder in place and the entire party slowly made its way into the tunnel.

“It was devoid of sound, but I remember the earth floor smelt a little bit like a forest,” said Diamond. “As soon as we got in, the four people from PANYC were huddling in a corner, talking, and excluding me.”

Still, Diamond generated press coverage and, more important, Golden and Smith, who were close allies, enthusiastically endorsed the idea that the tunnel should be open to the public and that Diamond conduct tours. They saw it as a great tourist attraction that would boost the local economy in an era when the neighborhood was largely graffiti-covered, boarded-up storefronts, Diamond said. Golden also envisioned the possibilities of establishing a light rail that could run through the tunnel on its trip from the Long Island Rail Road to DUMBO, connecting to a ferry that would travel to the South Street Seaport.

At the same time PANYC and the Landmarks Commission were threatening to sue anyone who opened the tunnel, “alleging the tunnel was being destroyed by a crazy kid who did not have the right permits,” Diamond said. “Who the heck are they to arbitrarily decide if someone has the right permits or not? Do you see how absurd this is? Gonifs!”

In response to my request for an interview PANYC Chair Lynn Rakos wrote in an email: “I am sorry but, following Mr. Diamond’s attorney subpoenaing me for documents related to Atlantic Avenue Tunnel project, which I was working on as part of a team for the National Geographic Society, and then Mr. Diamond posting the documents I provided under subpoena on his ‘Brooklyn Historic Railway Association’ website, I want nothing to do with him or any story related to him.”

Taken for a ride … a trolley ride

For almost a year, Diamond was frozen out of the tunnel, although he managed to book an invitation to appear on WNYC’s Marty Wayne-hosted show, on which he recounted his experiences, noting his desire to open the tunnel and see it used as part of a modern streetcar line that would employ old-fashioned trolleys, Diamond said. “Marty said, ‘That sounds good, but where do you think you’d get trolleys? They’re hard to come by.’ I said, ‘Tunnels are even harder to come by.’ ”

Thanks to his radio interview, a Staten Islander who owned a fully restored 1897 trolley offered it to Diamond if he could house it. Diamond also received an enthusiastic call from John Herzog, chairman of the brokerage firm Herzog Heine Geduld, who said, according to Diamond, “Well, young man, you need money and important people on your side and I can help with both.”

Herzog arranged for Diamond to meet with Jack Lusk, who was Deputy Counsel and Special Advisor to Mayor Ed Koch on transportation and environmental issues, and Lusk contacted David Walentas (of Two Trees Management Company in DUMBO), who offered Diamond space for the trolley at 88 Water St.

When Diamond noticed barely camouflaged freight-train tracks in the street around the property, Lusk asked him to dig the street up to see what lay beneath. Diamond pried away the asphalt, exposing the track and the original cobble-stone street and, in short order, Diamond’s trolley ride was inaugurated in DUMBO, accompanied by a festive marching band clad in 19th-century costumes and Keystone cops running amok.

Entertainment value aside, Diamond’s talents were taken seriously, and he was invited to meet with several major players who were promoting the idea of a light rail on 42nd Street in Manhattan, but had been unable to get their plans approved by the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure and City Environmental Quality Review because their plan required power plants that were large and polluting, Diamond said.

But he had a plan in place — based on his winning high-school science project — that was compact, clean, and had no impact on the environment. In fact, he continued, his project was the only operation of its kind in the city to receive City Planning Commission approval.

Ultimately, Diamond and his team were relocated to Red Hook to set up shop on a no-man’s land belonging to former cop Greg O’Connell Sr., who later converted an old warehouse into a waterfront Fairway. At that point, Diamond bought three more streetcars from the Transit Authority in Boston, and he was establishing an electric light-rail system that had patentable applications, he recalled.

Way ahead of his time — indeed, prescient in his foresight — in 1982 he founded the Brooklyn Historic Railway Association, a non-profit, educational organization, dedicated to creating a light-rail system in the outer boroughs. For years, Diamond had been insisting that light rail was spot-on from an environmental standpoint and debunking the well-respected feasibility studies on its high cost.

This was a happy period for Diamond who, with the help of Lusk, had also landed a franchise application for his tunnel tours and a clean bill of health from an engineering company, asserting that the tunnel was safe.

His tours were attracting as many as 800 people a day. He charged $10 a pop, and on a good day could roll up to $6,000 or $7,000. “Most of the money went into further research of the tunnel,” he said. “It was a non-profit, educational and cultural business. We were not in it to make money, just to keep it going.”

A 19th-century locomotive

Diamond’s research focused on what he believed was a fully intact 19th-century locomotive behind the tunnel wall. He faced plenty of skeptics but said his views were vindicated when Brinkerhoff Environmental Services, scanning Atlantic Avenue from street level and using a Cesium Vapor Magnetometer, was able to discern a highly magnetic, 20-foot object exactly where Diamond said it would be.

Matthew Powers, director of geophysical services for the company, wrote in an email: “It is conceivable that the suspect locomotive is located between the middle and south sides of Atlantic Avenue and a separate smaller anomaly is located on the northern side of Atlantic Avenue. Based upon Brinkerhoff’s interpretation of the geophysical data, there is no question that something(s) metallic is buried under Atlantic Avenue. It’s just a matter of what and in what orientation.”

Diamond was convinced that it’s a train dating back to the mid-19th century, “because when the tunnel was sealed in 1861, nothing except a locomotive would have utilized that much metal,” he contended.

Rumors about its presence go back more than a century. In a 1911 Brooklyn Eagle article discussing the tunnel, the reporter notes the existence of a wood-burning locomotive. A New York Times article, written in 1936, acknowledges the locomotive scuttlebutt, though no one interviewed had seen it. By contrast, a 1981 article in The Daily News quoted at length Juan Vega, a merchant seaman who claimed to have played as a child on top of the steam engine behind the tunnel wall.

Further, on the basis of Vega’s description and Diamond’s exhaustive research, Diamond speculated that the buried locomotive is the “Hicksville,” a 2-2-0 Planet type. Inspired by a locomotive originally conceived in the 1830s by British railway pioneer Robert Stephenson, it became obsolete by the 1840s. Diamond said that, when the tunnel was sealed in 1861, the locomotive was used to haul in dirt; after the engine broke down it was simply abandoned there.

“This is the only locomotive of that age in the entire world, in its original fresh-off-the-railroad condition,” he insisted. “In Brooklyn, we have an authentic piece of the very beginning of America’s industrial revolution, literally a time capsule, testifying to our country’s origins.”

Not surprisingly Diamond’s contention that a 19th-century locomotive lies on the other side of the tunnel wall was controversial. Most of the rail fans I interviewed — and they make up an intense subculture numbering in the thousands — were not convinced of its presence.

“Still, if a rare iron horse is indeed uncovered, this could present one of the most exciting transit ‘finds’ of the 21st century, not unlike discovering a sunken locomotive on the bottom of a lake, or buried in a long forgotten landfill, with all of its appurtenances intact,” said the nationally known railroad historian Kurt Bell, who served as railroad archivist at the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg. “If the engine still has all its ‘jewelry,’ such as the whistle, the bell, number and builder’s plates and all of its gauges, it will represent a valuable find of the first magnitude. The city should put speculation to rest by sending an exploratory party to the site. If in fact an engine survived, it would be the Holy Grail.”

As for the missing pages in the John Wilkes Booth diary, Diamond said that, during the Civil War years, the actor was frequently in the neighborhood, supposedly to perform at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. But, according to the Brooklyn Eagle, he was repeatedly playing to empty houses; and Diamond speculated he was not there to act at all, but rather used the performances as a pretext to meet with New York-based supporters of the South who subsidized its cotton industry and gathered to discuss battle plans.

“Almost every time there was a major battle in the South, John Wilkes Booth was in New York 10 days before,” Diamond said. “Even more interesting, the tunnel was filled up and shut down in 1861, but two weeks before Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, city records listing expenditures show that a contractor was paid $25 to open the back end of the tunnel. I can’t help wondering why.”

Diamond’s conclusions were wildly circumstantial at best — I found no one who supported the notion that John Wilkes Booth’s diary pages lie buried in the tunnel — but, in 1991, he received a DOT permit to open up the street at Atlantic Avenue between Hicks and Columbia, just behind the wall. A DOT engineer brought him together with a construction company and the work began. Two 10-foot holes, approximately four feet wide, had already been completed, “when some guy from DOT’s Highway Quality Assurance shows up and said, ‘You and your contractor have 10 minutes to get out,’ ” recalled Diamond. “‘And if you don’t you’ll be arrested.’ We only needed to dig one more hole to lift a piece of the street to see what was inside. They didn’t give a damn about our permit.”

The DOT did not respond to my calls or emails.

It was only going to get worse for Diamond.

The Red Hook effort

Red Hook is a stunningly incongruous community — filled with renovated Civil War warehouses sheltering a Fairway, chic art galleries, and honky-tonk eateries serving tourists, locals and punk-Goth hipsters who evoke East Village runaways in the 1980s. Perched on a strip of land at the far end of Van Brunt and adjacent to the New York Harbor, intrigued visitors stare, grin, and shoot photos of an abandoned 1930s streetcar, locked in place on two eroded train tracks.

Diamond, who said he was the rightful owner of the streetcar and 13 others that were scrapped without his permission, recalled that Red Hook during the ’90s was a windy, wet, and cold backwater of run-down buildings and deteriorating piers, but simultaneously a hub of activity and promise, at least for him.

The Fairway building’s owner O’Connell was not only willing to house four of Diamond’s streetcars and his 1897 trolley, he also gave the BHRA team 8,000 square feet of workshop and office space at 499 Van Brunt St. — which also served as BHRA’s trolley museum — in return for helping him to develop the pier.

Diamond understood Red Hook’s need for an ecologically friendly light-rail system.

“It’s an underserved neighborhood, and it would cut travel time from 45 minutes to 12 minutes. It would serve 16,000 riders daily, and the construction costs — if they were done right — would come to $13,000,000 a mile for a two-track line. Also, it would be cool.”

Diamond knew that light rail in New York is up against the oil interests — or, more precisely, the “compressed natural-gas bus-fuel industry” — which have a stake in maintaining buses coupled with locals who were worried about disruption and congestion and loss of affordable housing. No one seemed to know how the whole thing could be funded.

“Yes, but we have some radical solutions to these problems, which are nothing more than simply re-discovering the lost knowledge of how our city was originally built in the first place, such as using new rail transit capacity to help double the total number of housing units across the city while simultaneously creating many, many thousands of new well-paid construction jobs for literally rebuilding NYC from the infrastructure on up,” Diamond said. “By allowing capitalist forces to ‘normalize’ the relatively low population densities — by welcoming as many working-class newcomers as we can actively recruit — the city’s tax-base revenue would drastically increase without raising anyone’s taxes. No, this isn’t ‘zero-game-sum-theory thinking.’ It’s nothing short of creating a public-private partnership version of the WPA. Socially directed capitalist motivation is the way of the future, and NYC can and should serve as the model.”

In the ’90s, Diamond had broad-based support, including the Department of Transportation, which instructed him to start laying down the tracks on O’Connell’s property and agreed to sponsor his efforts with $300,000 in federal grant money. The MTA and Conrail contributed equipment, tools, and other materials.

Diamond said he should have known something was amiss when he did not see any monies for three years and he was asked to submit two sets of bills, suggesting cooked books. But he put his discomfort on a back burner when, in 2000, BHRA got a revocable consent to build tracks in the street and, a year later, a notice to proceed. BJRA was still short $98,000 in government funds, but started building anyway, he recalled.

Ironically, it got $50,000 from the City Council thanks to the efforts of City Council Member Angel Rodriguez, who later served time in jail for allegedly attempting to solicit a bribe from O’Connell.

“He wanted O’Connell to give him money under the table in return for his approval to proceed with building Fairway in Red Hook,” Diamond said. “But O’Connell was wearing a wire. This is Brooklyn. You gotta remember, this is Brooklyn.”

But the turning point came in 2002, when the DOT refused to extend the city’s sponsorship of Diamond’s project, alleging he hadn’t coughed up his agreed-upon share of the money, which came to about $90,000. Diamond said he contributed about $2 million in labor and equipment.

In fact, recorded minutes of a May 21, 1996 meeting between the DOT and BHRA reads as follows: “NYCDOT recognizes that BHRA has apparently raised and expended funds in excess of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act program required local match.”

But the rules of the game had abruptly changed, said Diamond, who remained convinced he was being asked to pony up money to compensate for funds that had been misappropriated. A city DOT official, who did not want to be identified, said in an email that disappearing monies within the agency is business as usual.

“It’s Tammany Hall re-invented for the 21st century,” said Diamond. “Years ago, they’d get $500 of public monies for a desk that cost $10 and pocket the change. “Now they’ll buy a desk for $500 that only costs $10. The money is gone and there’s no desk either. The only thing the public responds to is if someone is handcuffed and escorted out of a building with police. But then they’ll say, ‘He’s a bad apple.’ It’s not one bad apple. It’s systemic. If I was an insider and millions of dollars disappeared, I’d be flipping out. But it doesn’t seem to be bothering anybody one bit. Previously, it’s been the role of the NYC Comptroller to monitor/audit NYC agencies. But since the days of Harrison Goldin we haven’t really had one. Alan Hevesi went to prison. No wonder these city agencies get away with murder. No one is watching the store.”

In December, 2003, 1,500 feet of track that Diamond and his friends had installed — with city Planning Commission Approval and $300,000 in federal grants — were ripped up. The entire proposal was scrapped by the DOT, once again without issuing any formal explanation. All but one of the 15 vintage street cars (many sitting in the Brooklyn Navy Yard) that Diamond purchased largely at his girlfriend Sharon’s expense had been destroyed and Diamond was not paid a dime.

Off-again, on-again, off-again

Emotionally battered, Diamond found solace in Central New Jersey, where he lived off the grid in a druggy haze, until he cleaned up his act and returned to New York three years later, in 2006, whereupon the DOT, in a bizarre turn of events, asked him to resume his tunnel tours.

His future looked rosy especially when National Geographic Television contacted him in 2010, gearing up to make a documentary on the Atlantic Avenue Tunnel.

But it all went south when NATGEO teamed up with PANYC to authenticate Diamond’s find.

“There are many ‘professionals’ they could have contacted,” Diamond said. “But they chose to go with my worst enemy.”

The end came abruptly when Rooftop Films, which was slated to use the tunnel as a screening room, issued a press release, dubbing the program, “Trapped in the Tunnel and No Way Out.” The Fire Department saw the ads and promptly cancelled the screening, although the tours continued.

Two weeks later, Diamond received the worst call in his life, from a DOT official informing him that his franchise was being revoked because he had allegedly applied for a permit to dig up the street when that idea had been nixed 20 years earlier.

“You’re a sneaky little bastard,” the caller said, according to Diamond. “You’re looking for the train behind the wall and you’re planning to put holes in the street and we caught you.”

Diamond said he responded, “What?” and was told, “I have your application for a permit right in front of me and it’s dated from November.”

He said he had never applied for that permit and signed nothing.

“Then I hear her whispering to someone, ‘Oh, shit, it’s not his signature,’ and then she hangs up,” Diamond said.

The next thing Diamond knew, the tunnel was sealed shut.

Diamond maintained he that was targeted for his ongoing comments about pilfered DOT funds and believed that NAT GEO played a role in the tunnel shuttering by not following correct protocol to obtain permits.

“I don’t know why they wanted me out of the picture,” Diamond said.

Interoffice emails among NATGEO staffers — which his attorney had obtained through discovery — did indeed indicate that they viewed Diamond as a difficult personality (one email dubbed him “a little old lady in tennis shoes”) and wanted to distance themselves from him. BHRA hit NATGEO with a $16-million lawsuit for breach of contract, mental distress, misappropriation, and unfair competition. The suit was ultimately “resolved.”

To date, no one is back in the tunnel and, until the end of his life, Diamond mourned the loss of his 11 streetcars that were housed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard until 2006 and the four others that remained on Fairway property for more than a decade. They were all in various stages of restoration, and Diamond was continuing his battle for a streetcar system in Brooklyn.

But the Navy Yard did not think the streetcars had a future, and saw no reason to serve as their parking lot. The yard alleged that he owed it unpaid rent. He said he was in the hospital at the time. Either way, after failing to sell the streetcars on the Internet, the Navy Yard sold them for parts, said Diamond. Other property he owned, totaling more than $600,000, was confiscated by the DOT, he said. “I filed a police report, and I was stonewalled.”

Diamond was no stranger to a Kafkaesque world and had yet another taste of it, in 2014, when Fairway’s new owner, Greg O’Connell Jr. — who did not respond to my request for an interview — had three of Diamond’s remaining street cars carted off on a flatbed trailer to the Branford Electric Railway Association, which operates the Shoreline Trolley Museum in East Haven Connecticut. The museum said it was going to provide temporary housing for the Hurricane Sandy-damaged streetcars in the hope that some other, like-minded museum might want to restore and display them. If not, they would be scrapped.

“They went to the junkyard,” said Diamond. “And I learned about all of it after the fact.”

Many observers to the Diamond morass felt that he had brought the situation on himself, thanks to his impatience, inability to negotiate and, most centrally, his contentious style and allegations; others suspected that there may have been some truth to his allegations that payback played a role.

Herzog said, “If not [for] payback, the reactions to him would have been less severe. I know Bob is not the most diplomatic guy, so it boils down to his personality versus the city’s power. I don’t like it when our government does something hurtful to someone else. They overlook a contract they signed and then rip up the tracks and sell the trolleys. It sounds like an awful administrative decision, and the city should be called to account. Bob’s discovery of the tunnel was a spectacular accomplishment.”

Sam Schwartz (aka “Gridlock Sam”), a leading national transportation engineer who served as the New York City traffic commissioner (1982-1986) and as a DOT deputy commissioner (1986-1990), agreed, adding, “The city’s treatment of Diamond has been a travesty. It’s a shame the city has given him such a hard time. The city should support and encourage people like Bob. The tunnel tours should be resumed, and Bob’s research pursued. Someday, he’ll be recognized as a genius.”

Peter Yost of Pangloss Films, who was slated to produce and direct the documentary for NATGEO, added: “Something has been lost by not having Bob in the tunnel. He was a bridge to the history that was accessed through the tunnel, and he himself represented another era: scrappy, devil may care, screw the bureaucracy. Bob also represents the magic of discovery in the city. How he discovered the tunnel is the stuff of childhood story-telling, but it’s real. In a time of condos and impact studies, he was a throwback, and people gravitated toward him and were moved by him.”

The end

During the last few years, Diamond was largely confined to his apartment, a situation made worse by COVID. At one point, he was battling an infestation of bed bugs and, worse, the inept cleanup crew sent to correct the problem. But, mostly, he was just plain bored with little to do short of visits to a psychotherapist and physical therapist who treated his sciatica by administering a series of escalating electric shocks to the affected areas.

He also complained of pain in a phantom tooth, or “toof” as he called it. “And I hardly have any teeth,” he said.

Diamond confessed that he had been running on empty and perhaps had made some wrong choices in life.

“My one regret is that I never ran for public office,” he said. “I’d like to have been another William Gaynor or Seth Low.”

Bob Diamond is survived by Sharon Rozsay, his companion of 25 years, and his poodle, Goldie. An outdoor funeral will be held at Green-Wood Cemetary at a date to be determined. Funds are needed to cover expenses. Checks can be made out to Sherman’s Flatbush Memorial Chapel and mailed to BHRA, 599 E. Seventh St., Suite 5A, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11218.

Simi Horwitz is an award-winning feature writer/film reviewer who has been honored by The Newswomen’s Club of New York, The Los Angeles Press Club, The Society for Feature Journalism, the American Jewish Press Association, and the New York Press Club (among others). The publications that have printed her work include The Hollywood Reporter, Film Journal International, American Theatre, and the Forward. She was an on-staff feature writer at Backstage for 15 years.