If the Uber driver had hit Velma Mitchell two miles farther north, things would be different.

Nine screws and a plate may still be holding Mitchell’s ankle together. Her landlord may still have tried to evict her over unpaid rent after the crash because she couldn’t work while in rehab learning how to walk again. And she may still be mostly housebound — because her body hurts constantly and because getting hit by a 3,000-pound SUV while legally walking in a Bronx crosswalk has left her terrified of the streets of New York City.

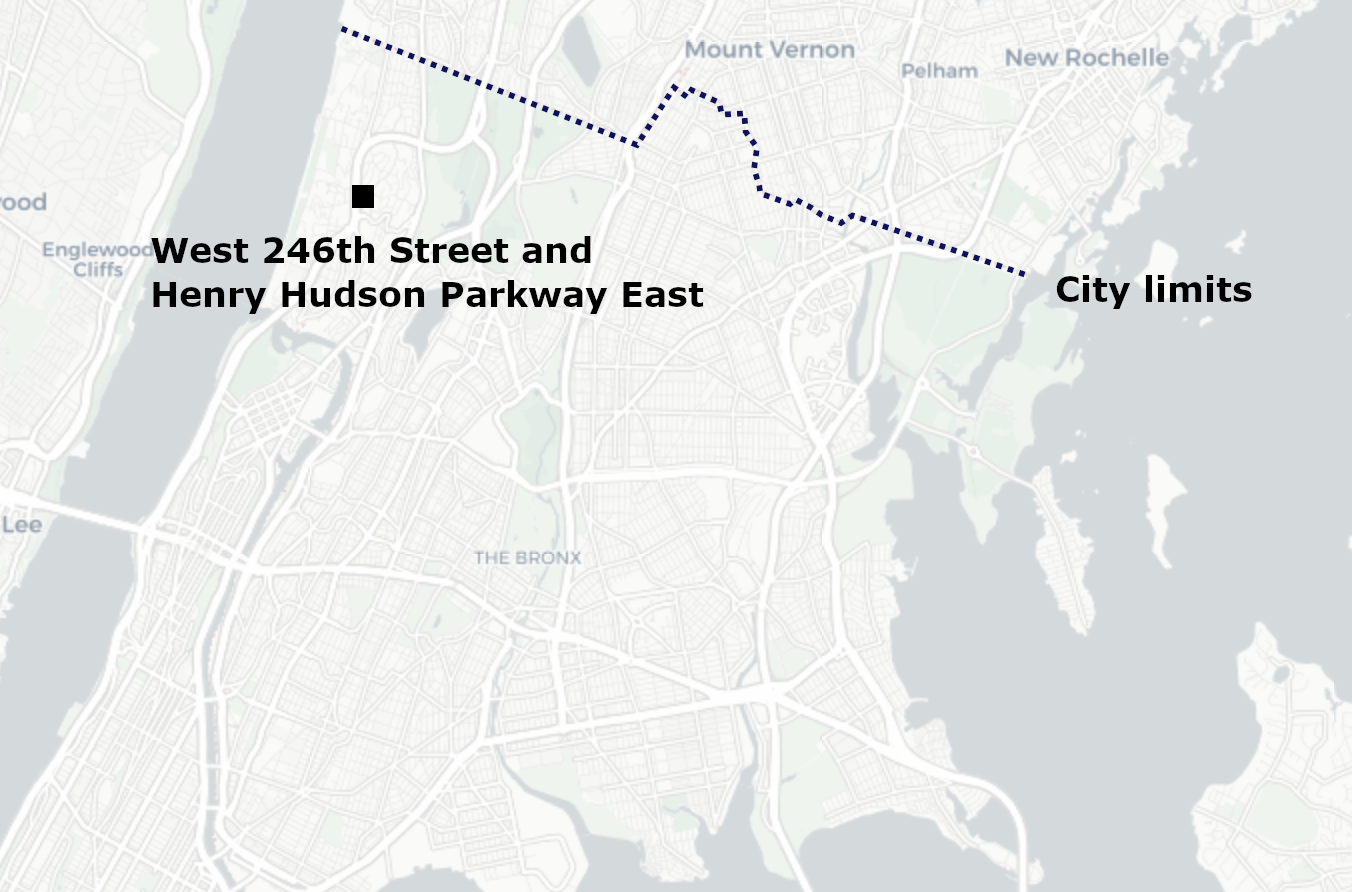

But if the crash had occurred just miles north, that would have put it beyond the city limits. There, the driver who hit her would have had $1.25 million in liability auto insurance, which compensates car crash victims like Mitchell for their losses, including pain and suffering. That’s the same $1.25 million that Uber and Lyft taxis carrying passengers must have everywhere in the state.

Everywhere in the state except for New York City.

Instead, the driver, Nima Sherpa, hit Mitchell in the Bronx, where W. 246th Street crosses over the Henry Hudson Parkway. In the city, the Taxi & Limousine Commission (TLC) requires Uber drivers like Sherpa to carry only $100,000 in liability insurance per crash victim, no matter how severe their injuries. So for all her pain and suffering, that $100,000 is all Mitchell is likely to get from Sherpa.

“It’s very unfair,” said Mitchell, 61, of the Bronx, who cannot return to her job as a nanny and now lives on $907 a month in disability pay. “It doesn’t matter where you got hit. You’re supposed to be taken care of.”

But it does matter. State law requires drivers logged into the Uber and Lyft apps but not carrying passengers to be covered by $75,000 in liability insurance for one person killed or injured in a crash. When drivers accept trip requests or have fares on board, the requirement jumps to $1.25 million to reflect the risk faced by passengers.

But the state exempts the city from those mandates. Instead, the TLC requires the roughly 80,000 app-based taxi drivers in the city to carry only $100,000 in liability insurance for an injured person — the same that’s required of yellow cabs and other for-hire vehicles with fewer than eight passengers. The city hasn’t raised that minimum insurance requirement in decades, even as medical costs have soared.

This $1.15-million disparity shortchanges the city’s crash victims, a Streetsblog investigation found, leaving far less compensation for people severely injured by app-dispatched taxis carrying passengers in the five boroughs than anywhere else in the state.

That inequity exists even though the risk of getting hit by a car while on foot or bike is far higher in the city. Pedestrians and cyclists are twice as likely to be killed or seriously injured by a car in the city than elsewhere in New York, crash data shows. Thousands of “black cars” — the TLC category that includes Uber and Lyft cars — get into crashes involving injuries each year.

Attorneys for people injured by Uber and Lyft drivers said individual crash victims in the city rarely receive much more from vehicle owners for their pain and suffering than the $100,000 in TLC-mandated liability insurance, a sum that often fails to match the true cost of their injuries.

“There’s no reason why people in the five boroughs should be afforded less protection than people outside of the five boroughs,” said Halina Radchenko, president of the New York State Trial Lawyers Association, which has pushed for higher insurance requirements for app-based taxis and other commercial vehicles. “There should not be a discrepancy like this in the law.”

The city also requires cars on the platforms to carry $200,000 in “personal injury protection,” also called “no-fault” insurance, which is more than the $50,000 required in the rest of the state. But no-fault insurance is meant to promptly cover medical bills and lost wages caused by a crash, not the long-term pain and suffering that may follow, which have merited multi-million dollar judgments and settlements for city crash victims.

Many victims’ lawsuits name Uber and Lyft as defendants. But the tech giants argue in court that drivers on their apps are independent contractors, not employees, and therefore the companies aren’t liable for injuries they’ve caused.

The companies seemingly always settle before going to trial when a seriously injured plaintiff brings a credible suit, attorneys said. Those settlements come with strict non-disclosure agreements, obscuring how much financial responsibility the multi-billion-dollar firms take for crash injuries.

The disparate regulations put drivers and passengers at risk, too. Outside the city, the state requires Uber and Lyft cars carrying passengers to have $1.25 million in uninsured and under-insured motorist coverage, which compensates people hit by drivers with little or no car insurance. In the city, the requirement only goes up to $100,000.

Streetsblog reviewed hundreds of pages of court records and interviewed dozens of attorneys, lawmakers, insurance brokers and industry officials for this story. Many attributed the disparity to the fractured regulations for the digital ride-hail industry in New York, where the state’s largest city is exempted from relevant laws and allowed to maintain its own rules for the behemoth technology outfits.

So it is that Uber and Lyft cars are officially “high-volume for-hire vehicles” in the city, but “Transportation Network Company” cars everywhere else in the state. In the city, Uber, Lyft and Via are permitted to operate; in the rest of the state only Uber and Lyft. In the city, the car owners have to buy commercial auto insurance; in the rest of the state Uber and Lyft pay for the policies.

Many defended the TLC, noting the agency has stiffer requirements for app-based taxis than many other cities.

“They’re one of the premier regulatory bodies in the country,” said Brendan Helt, an account analyst with Research Underwriters, an insurance brokerage that represents thousands of the city’s Uber and Lyft taxis. “They have a lot of safeguards in place to protect the public and ensure that the people behind the vehicles, and the vehicles themselves on the road, are safe.”

Asked to comment for this story, TLC Commissioner and Chair Aloysee Heredia Jarmoszuk said in a statement: “The TLC requires insurance coverage for TLC-licensed vehicles in excess of the state minimum insurance levels. In addition to excess coverage, TLC-licensed vehicles can only be operated by a TLC-licensed driver.”

Heredia Jarmoszuk did not address the insurance disparity that leaves city crash victims at risk of meager compensation for their losses. That’s the risk facing Velma Mitchell, said her attorney, Steven Halperin.

“That $100,000 cap is a disaster if you have an injury like she had,” he said.

The carve-out

Two years before Nima Sherpa hit Velma Mitchell, lawmakers in Albany were hashing out a deal to let Uber and Lyft operate across New York. By then, in early 2017, New York City was the only place in the state where drivers using the apps could pick up fares, and the burgeoning tech firms wanted to expand to untapped markets from Buffalo to Long Island.

The expansion campaign was nearing its third year, and Uber and Lyft had already spent millions of dollars lobbying lawmakers, state filings show. Key legislators supported the idea, and had pushed bills in 2015 and 2016 that would have green-lit the expansion, according to news reports from the time.

But those bills didn’t survive, each snagged on the same issue: insurance.

The Trial Lawyers Association wanted app-based taxis to carry at least $1.5 million in insurance, according to an Uber official involved with the negotiations. That would ensure ample compensation for crash victims and big fees for the attorneys representing them. But Uber wanted lower requirements, Assemblyman Kevin Cahill (D-Kingston) said — and the company wasn’t subtle about it.

“Uber was ruthless,” said Cahill, who chairs the body’s insurance committee and led the negotiations. “It was a two-year fight to get them to have anything over and above what a regular private car owner would have for insurance.”

Private cars in the state must carry insurance that pays out at least $25,000 for one person’s injuries and $50,000 for their death

The Uber official noted a model bill developed by the National Conference of Insurance Legislators proposed a $1-million insurance minimum.

Finally, in spring 2017, a compromise was reached: $1.25 million during a “prearranged trip,” which runs from when a driver accepts a trip request until the passenger exits the vehicle.

But there was another issue: New York City. The TLC already had extensive regulations for Uber and Lyft. Far from the “ride-share” model touted by the tech firms, in which everyday car owners make money on the side by picking up the occasional fare, the TLC required digital ride-hail drivers to operate like other for-hire drivers in the city: take safety courses, get a TLC license, buy commercial insurance.

Such requirements had earned the TLC a reputation as perhaps the most stringent industry regulator nationwide. State lawmakers didn’t want to meddle.

“It was understood that the TLC had a system that was functional for the city,” Cahill said.

So meddle they did not. Buried in the state law establishing minimum insurance requirements for cars on Transportation Network Company (TNC) apps is an exemption for cities of one million people or more. In other words: New York City.

The arrangement seemed to suit all involved.

“New York City lobbied against the TNC laws,” said Matthew Daus, who ran the TLC from 2001 to 2010. “They already have an operation that works for them.”

Meera Joshi, who ran the TLC in 2017 and is now deputy administrator of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, declined to comment.

The Uber official said the company would have preferred uniform insurance requirements statewide but didn’t complain.

“We lived under the TLC regime for so long, we were happy to continue doing so,” he said.

The carve-out had upsides for Uber and Lyft: the firms wouldn’t have to start buying insurance for their drivers in the city.

The legislation was tucked into the state budget, which passed that April. As for the insurance disparity it created, no one interviewed by Streetsblog remembers it being a concern.

Is Uber liable?

As Uber tells it, the gap is smaller than it seems.

“Not only do licensed professional drivers in New York City, under the TLC’s regulations, have some of the strictest insurance requirements in the entire country, but we also maintain an additional $1-million auto liability insurance policy on all NYC trips while a passenger is in the vehicle,” Uber spokesman Harry Hartfield said.

That supplemental insurance, he said, is available to passengers injured in crashes as well as those outside the vehicle, including pedestrians and cyclists. (Lyft spokesman CJ Macklin did not respond to a question about whether Lyft carries additional insurance for drivers in the city, or answer other questions, but it appears the company does.)

But attorneys who have represented people injured by Uber drivers said that extra insurance is hard to come by.

“In my negotiations with Uber, I’ve had attorneys deny that even exists,” attorney Joseph Bavaro said of Uber’s supplemental insurance. “You’re only going to get the discovery that an ethical attorney’s going to give you.” Bavaro’s firm has represented around a dozen people injured by ride-hail app drivers.

Even when the existence of the extra insurance is clear, Uber routinely argues in court that it isn’t responsible for injuries caused by its drivers, as they are independent contractors, not employees.

“They’ll fight you before that million dollars becomes available to you,” said Peter Beadle, an attorney representing a Manhattan pedestrian whose skull was fractured by an out-of-control Uber car three years ago.

Whether Uber is responsible for injuries caused by its drivers is an open question in New York law, Beadle said, and one that the company does not appear eager to see answered.

“There’s incentive on both sides of this litigation for nobody to get a formal decision,” he said. If a judge rules Uber liable for crashes, it would set a costly precedent for the company; if a plaintiff rejects a settlement from the company only to lose in a trial, she may get nothing from Uber.

The attorneys interviewed for this story have collectively litigated more than 100 cases against Uber, Lyft and Via. None of their claims against the companies went to trial. Instead, many ended in voluntary settlements accepted by plaintiffs, with non-disclosure agreements attached.

An Uber official said he could not comment on settlements with crash victims.

Once the tech company exits a lawsuit, that often leaves just the vehicle owner and driver for a victim to pursue. About half of the app-based taxis in the city are owned by fleet operators, Helt said, with the other half owned by drivers themselves. Often those drivers have few assets to sue for beyond their insurance.

For city residents badly injured in crashes, that leaves little hope for just compensation. Medical bills from extreme crashes can exceed half a million dollars, said Daniel Flanzig, whose law firm has litigated more than ten cases against Uber and Lyft. And that doesn’t account for so-called “non-economic damages” — like suffering a debilitating injury that ruins your life.

‘Just an accident’

Velma Mitchell filed suit against Sherpa and Uber in March 2019, two months after she was hit and halfway through a 71-day stay in a rehabilitative care center. The crash had shattered her ankle and required surgery the same day. She stayed in the hospital more than a week after that.

Before the crash, Mitchell was a nanny caring for three young children in Riverdale. She was heading to work when she was hit, on the last leg of a three-mile commute across the Bronx that involved three buses and took more than an hour.

Mitchell worked 10-and-a-half hour days and earned $650 a week — about $12.38 an hour. After the crash, that income disappeared, and she couldn’t pay rent. Her landlord commenced eviction proceedings while she was in rehab, she said, but the city’s Department of Adult Protective Services Program intervened to keep her in her apartment.

Mitchell doesn’t know the total cost of her medical bills and lost wages. By now, her lost income probably amounts to more than $78,000. Her hospital stay alone cost more than $150,000, a court filing shows.

Mitchell said most of her medical bills were covered by Sherpa’s no-fault insurance. But the policy provider, Maya Assurance, refused to pay out the $100,000 liability insurance, Halperin said, so Mitchell had to bring the suit to receive it.

Maya Assurance did not respond to requests for comment.

In court, Uber argued it wasn’t liable for Mitchell’s injuries.

“Uber Technologies, Inc. expressly denies any employment, agency, and/or servant relationship with defendant Nima Sherpa,” the company’s lawyer wrote eight times in a filing. “Nima Sherpa was an independent contractor responsible for his own means and methods.”

Uber settled its side of the case with Mitchell earlier this year. (Halperin declined to discuss the settlement, citing a non-disclosure agreement.) That leaves Sherpa’s $100,000 insurance policy as all that’s left to win in the suit.

“He probably makes enough to live on and maybe a little bit more than that,” Halperin said. “I’m not going to go after him for more than the insurance he carries.”

Sherpa, who was carrying a passenger during the crash, said in an interview translated from Nepali by his daughter that he didn’t see Mitchell crossing the street.

“When I was about to turn left, all of a sudden — I didn’t even see the lady — but when I was turning left, she got struck,” he said.

“I feel very sorry for her,” said Sherpa, 61. “I didn’t do anything on purpose. It was just an accident.”

‘A tragic result’

There’s another way the city’s exemption from state insurance requirements hurts city residents. The family of Mohammed Hossain knows this all too well.

Hossain, a Lyft driver, was carrying a passenger in Queens in June when an intoxicated 22-year-old motorist ran a red light and slammed his Ford Explorer into Hossain’s car, killing him.

The driver didn’t have insurance, leaving Hossain’s uninsured motorist insurance as seemingly the only compensation available to his wife and three children for his death.

If the crash had happened ten miles east, beyond the city limits, that insurance would be worth $1.25 million. That’s what the state requires of Uber and Lyft cars carrying passengers outside the city. Instead, the family will receive only the state minimum for one person’s death, which is all the TLC requires: $50,000.

Marc Albert, the family’s attorney, said Lyft says it has no other insurance to compensate Hossain’s wife and children.

If that’s true, then “the only reason that this family is going to get 50 grand instead of $1.25 million is because the ride originated in one of the five boroughs,” he said. “This is an absolutely ridiculous result, and a tragic result for this family.”

No easy fix

Even if lawmakers wanted to close the insurance disparity, there may be no simple way to do it. Ride-hail app drivers in the city made on average about $20.50 an hour after expenses in 2019, not including tips, according to an estimate by Michael Reich, an economist at University of California, Berkeley. Asking them and other for-hire vehicle drivers in the city to buy policies with 10 times the coverage would put many out of business.

“The entire industry would collapse,” said Steven Shanker, general counsel for the New York Livery Fund.

Still, the TLC could at least narrow the gap with a modest increase to minimum insurance requirements for for-hire vehicles. But the agency hasn’t done so in more than 20 years, and it was a brawl the last time it did, said Daus, the former TLC commissioner.

Raising insurance minimums for app-based taxis in the city could be more palatable if Uber and Lyft started paying for insurance in the city like it does everywhere else in the state. But Uber officials noted state law effectively prohibits the company from buying group insurance in the city, which is how it covers cars elsewhere in New York.

The state could simply raise insurance requirements for everyone. That’s an idea favored by Cahill, the assemblyman.

“Liability insurance in automobiles is too low across the board,” he said. “These limits were created at a different time, when setting a broken arm cost 100 bucks. That’s not the case anymore.”

Every year, Cahill introduces a bill to increase insurance minimums for all vehicles. But it never goes anywhere.

“The insurance industry has convinced the general public and convinced my colleagues that it will dramatically increase the cost of car insurance,” Cahill said — a view he doesn’t share.

Another solution: create a supplemental public car insurance fund to subsidize payouts to crash victims when drivers’ insurance is insufficient. New York has a similar program for medical malpractice insurance, Cahill said.

But does the gap even need to be closed? An Uber official said the TLC minimums are higher than requirements for regular taxis elsewhere in the state. And perhaps it makes sense for Uber drivers outside the city to carry more insurance, given they’re more likely to be picking up passengers as a side gig, not a full-time job.

Helt, the insurance broker, also said most crashes in the city aren’t that serious — although there are more of them — as traffic speeds are typically lower than in more suburban or rural regions.

“A lot of people think $100,000/$300,000 is adequate,” Helt said, referring to the the TLC requirements. “There’s a lot of claims, but none of them are particularly bad.”

Still, close to 3,900 people were killed or seriously injured in car crashes in the city in 2019, including more than 1,600 pedestrians and cyclists, according to data from the Albany-based Institute for Traffic Safety Management and Research. Another 13,300 people suffered less severe injuries.

The threat to pedestrians and cyclists is especially lopsided. There were 500 more pedestrians or cyclists killed or seriously injured in the city in 2019 than in the rest of the state combined. Those on foot and bike were twice as likely to be killed or seriously injured in the city.

And close to 8,000 TLC-classified black cars, which are overwhelmingly app-based taxis, were involved in crashes causing injuries in 2019, city data shows. As for the rest of the state, DMV spokesman Tim O’Brien and a DFS spokesperson said their agencies — although tasked with regulating Uber and Lyft — do not track the number of people killed or injured by drivers on the platforms. They would not answer other questions for this story.

Failure to yield

Velma Mitchell walks with a cane now, when she walks at all. Sometimes she circles her block, but by the end her ankle is stiff, swollen and numb. So mostly she stays home. She has Type 2 diabetes now, too, which she developed in part because she now moves around so much less.

Sometimes she has flashbacks to the crash: the bright, cold January morning, the sound of cars streaming by on the Henry Hudson, the black SUV bearing down on her in the crosswalk. She avoids large roads. If she has to cross one, she’ll wait until a group of people is crossing and walk next to them, trying to keep up.

“Every time I cross the street I just feel like something is going to hit me down,” she said in her deposition.

She hasn’t resumed working as a nanny since the crash and maybe never will. It’d be hard to run after young children when she can’t stand at the stove long enough to cook dinner. She is still in debt to her landlord, although members of her church helped pay it down.

The $100,000 insurance payout would help, she said. But she’s potentially years away from receiving it. When she does, her attorney will take one-third of it. Without being able to work, Mitchell fears $66,000 will not keep her housed long term.

But two thirds of $1.25 million would. The first thing Mitchell would do with the money is buy a house, she said, so she’d never had to face eviction again.

“I’d find some way to live decently,” she said. “You just want to know that you have somewhere to live.”

If the crash had happened two miles farther north, beyond the city limits, Halperin said he “absolutely” would seek the $1.25 million in insurance Sherpa would have, and Mitchell likely would receive much more than she will in the city.

Sherpa is still driving for Uber, he said — the same SUV that hit Mitchell. The car wasn’t damaged in the collision. The total cost of the crash to him was a $200 ticket for failure to yield — which at least strengthened Mitchell’s case against him. The police didn’t ask Sherpa any questions about the crash, he said, and Uber didn’t either.