MTA, Feds Promise Congestion Pricing Won’t Start For A Long, Long Time

Meanwhile, transit users and communities of color will suffer.

It’s a new kind of idling.

The MTA confirmed on Friday that it will take 16 more months to complete the required environmental assessment for congestion pricing — a timeline that includes months of public meetings and briefings to determine if reducing driving into the central business district of Manhattan will be good for the environment and for long-suffering communities of color that have borne the brunt of decades of damage from the automobile.

Per an agreement between the transit agency and the federal government, the MTA, the New York State DOT and the New York City DOT will begin the lengthy outreach process in the coming weeks, and work on it through December 2022. The MTA argued in its press release that the 16-month process was a stroke of good luck for the traffic toll.

“The 16-month time-frame is actually shorter than those done for many projects with relatively small geographic, population and environmental footprints,” the agency wrote in the Friday afternoon press release.

The public — which includes Mayor de Blasio, who this week called the timeline “ridiculous” in its length — could be forgiven for thinking congestion pricing would be in place (or at least well on the way) already. The tolling plan passed the state legislature in 2019, but then was delayed by the Trump administration. During that year-plus purgatory, the MTA’s claimed it would only take three months to finish the EA.

Now, witness the unprecedented scale of the enhanced environmental assessment:

Environmental Assessment and Outreach Unprecedented in Scope

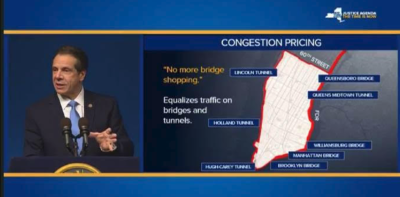

Incorporating and documenting all this public input, the Project Partners will create an Environmental Assessment document analyzing the impact of Central Business District Tolling on traffic congestion, transit, air quality and numerous other environmental indicators in 28 counties across New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. All told, the Study Area contains 22 million people, including 12.3 million residents residing in environmental justice communities, and five Tribal Nations.

The EA will make use of nearly a dozen different models and data sets to assess impacts to traffic and public transportation for a regional transportation network with 28.8 million journeys per average weekday, 61,000 highway linkage points, 4,600 traffic analysis zones, 44,267 bus stops or transit stations, 4,170 transit routes, and more than a dozen public transportation providers in addition to the MTA, including NJ TRANSIT, PATH, ferries, and regional bus systems including Westchester County Bee-Line, NICE, and Suffolk County Transit.

The MTA’s list of labors begins with meetings between the agency and the governments of New Jersey and Connecticut. The transit agency has had introductory meetings with its Connecticut counterparts, and the state’s DOT commissioner has indicated support for the congestion toll. It’s a different story in New Jersey, where the state’s congressional representation has said that congestion pricing is an unfair burden for residents looking to drive to the city to see Bruce Springsteen’s one-man show on Broadway. (In fact, Jersey drivers are already tolled to enter the congestion zone.)

There will also be at least 13 virtual public meetings in the process, 10 of which will allow “individuals and stakeholder groups” to learn what congestion pricing is and comment on it, starting in September.

An additional three virtual public meetings in October will specifically focus on environmental justice communities. Environmental justice groups in the New York City area said in August that the MTA had not approached them, and urged the agency to expedite the process so that low-income communities whose populations overwhelmingly depend on a working mass transit system can have a functioning mass transit system.

Beyond the 13 virtual meetings, the MTA is also offering briefings for community boards, elected officials, transit and environmental advocates, and any other interested parties.

There will also be a further public comment and meeting period on the environmental assessment itself after it gets published. The press release did not reveal when the Traffic Mobility Review Board, the panel appointed by the MTA Board to recommend toll rates and exemption policies to the MTA, will be appointed or meet.

The path to the agreement on the 16-month EA process was not without its share of controversy, including charges from transit advocates and environmental justice groups that the MTA was slow walking the project, possibly as a political measure to protect soon to be ex-Gov. Cuomo from political backlash for instituting tolls before the 2022 gubernatorial election. One of those critics was de Blasio, who has called on the agency to speed up the implementation of the program (using that word “ridiculous”). Hizzoner’s brickbats continued in the MTA’s press release:

“I appreciate the commitment of our state and federal partners to this project and look forward to working with them to further expedite the process,” said NYC DOT Commissioner Hank Gutman.

If the federal government deems the EA satisfactory, tolling vendor Transcore will have 310 days to go live. According to the preliminary congestion pricing schedule the MTA gave the federal government in 2019, there’s a one-month testing period before the system goes live, and tolls don’t start to get collected until 60 days after the tolling equipment is turned on.

The path in front of the MTA means that the agency will not start collecting money from congestion pricing until midway through 2023 at the earliest, or two years after it initially planned to collect money from the traffic toll. The agency has suggested that its $51-billion 2020-2024 capital plan is not threatened by the missing $1 billion per year that congestion pricing will raise, but government watchdog Reinvent Albany recently reported that the capital plan is not being funded at the rate that previous capital plans have been funded at.

The long road ahead also is getting started as congestion on the city’s streets as scores of thousands more New Yorkers buy cars and traffic reaches levels seen before the coronavirus pandemic before the post-Labor Day office crush begins.

Incoming Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine said that city can’t sit on its hands during the EA process. “We need to take emergency measures, like dedicated bus/HOV lanes on East River bridges,” he tweeted on Friday.

Congesting is already mounting in Manhattan at a truly alarming rate. And congestion pricing is now being pushed back to late 2023.

We need to take emergency measures, like dedicated bus/HOV lanes on East River bridges. https://t.co/6TUlTMSx5O

— Mark D. Levine (@MarkLevineNYC) August 20, 2021