The Bronx is Up: DOT Proposes Protected Bike Lane Under the White Plains Ave. El

Now that’s a vision.

A Department of Transportation plan to repurpose dangerous and ambiguous road space underneath a stretch of elevated train tracks in the Bronx into a protected bike lane should become the gold standard for the hundreds of miles of roads under elevated highways, rail lines and bridges across New York City, advocates say.

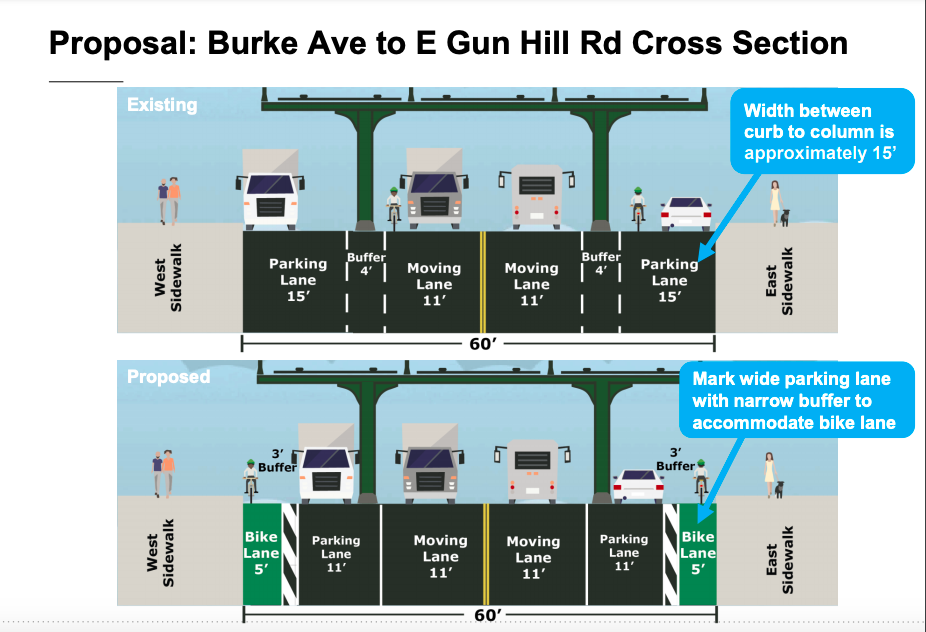

Last month, the DOT unveiled designs to Bronx Community Board 12 for a two-way protected bike lane on White Plains Road between Burke Avenue and E. 226th Street — plans that call for nixing several lanes of traffic, removing illegal parking, and adding pedestrian crossings where they are missing. The proposal will finally bring safer bike and pedestrian infrastructure to a borough that’s historically been neglected, and which had the highest increase in cyclist injuries last year, the agency said.

“Hopefully it will be the standard bearer for other areas that need it,” said Luke Szabados, a Bronx resident who attended the presentation last month, referring to other streets like Jerome Avenue. “I am really impressed.”

Currently, White Plains Road is a mess of multiple parking and moving lanes, varying in some parts between one and three, with much of its empty space taken up by illegally parked cars. And it’s acutely dangerous for the pedestrians and cyclists who try to traverse it because of the elevated train tracks, which enshroud the road below it in darkness and whose pillars create poor visibility.

And the rampant double-parking on the busy corridor, which also serves as a local truck route, has been the root cause of 16 percent of vehicle crashes, according to DOT. Between 2014 and 2018, the agency says there were 411 injuries on the 1.25-mile stretch of White Plains Road, with nearly a quarter of them caused by drivers who failed to yield to pedestrians.

Now, DOT wants to make the road safer, but the changes will depend on its existing circumstances. For instance, from E. 216th to E 226th street, where the road has 11-foot moving lanes in each direction flanked on each side by columns, and then 19-foot parking lanes, DOT will keep the two moving lanes as is, and merely shrink the parking lanes from 19 feet to 13 feet to make room for a five-foot buffer and six-foot bike lane on each side (see below):

And between East Gun Hill Road and E. 216th Street, DOT will reduce the haphazard roadway to just one lane of traffic in each direction by moving curbside parking next to the elevated train columns, installing a curbside protected bike lane in each direction, and adding in pedestrian crossings at E. 211th and E. 215th streets.

The plan is a first for elevated train structures in the city. There are currently some raised lanes under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and Bruckner Boulevard, and conventional lanes under 12th Avenue in Manhattan, according to DOT.

“Seeing protected bike lanes under the El that’s exciting because there’s so many streets like White Plains Road that could see the same treatment as well,” said Michael Kaess, a Bronx cyclist. “Riding under White Plains Road is challenging because everything is so unpredictable — there’s such undefined space because people double park.”

Last year, Streetsblog reported on the steady rise in injuries to Bronx cyclists, which started last April with an increase of nearly 30 percent — a blood tide that continued through 2020, and now into this year, when so far 155 riders have been injured, compared to 112 over the same period last year, or an increase of 38.4 percent, according to NYPD.

And of the 26 cyclists that died on the streets of New York City in 2020, eight were killed in the Bronx, which has just 3 percent of the city’s protected bike lane infrastructure, while Manhattan has more than 50 percent of it, according to advocates.

Local pols and safe streets advocates attributed the steady rise in injuries to poor infrastructure. When the city announced it was installing nine miles of pop-up bike lanes to aid in the city’s pandemic recovery, for example, none was in the Bronx. And when the city announced its Green Wave plan in 2019, very little was planned for the Bronx.

That has begun to change, however, with more recent announcements, however.

“When the Green Wave was first announced there wasn’t really all that much for the Bronx. This year they’re really focusing on the Bronx, it’s great it’s finally receiving attention,” said Kaess.