What Is The MTA Assessing In Its Congestion Pricing Environmental Assessment?

The MTA finally got long-awaited clearance from the federal government to move forward on congestion pricing by doing an environmental assessment rather than a full-blown environmental impact statement. But most people don’t know what will be assessed by the environmental assessment. So here’s a primer:

The goal is to get a FONSI.

Supporters have long argued that congestion pricing will reduce traffic and boost transit — but the MTA must still show in an Environmental Assessment that the effects of congestion pricing will indeed be positive and are thus worthy of a Finding of No Significant Impact, or a FONSI (“Ayyyyyy“) from the Federal Highway Administration.

If the MTA gets a FONSI (“Ayyyyyy”) will allow the MTA to avoid having to do a full-scale environmental impact statement, which typically takes much longer than an assessment. But getting a FONSI (“Ayyyyyy”) isn’t automatic; the environmental assessment will have to analyze more than just the potential traffic impacts of congestion pricing. It also means determining if the traffic toll could wind up impacting historic districts or local fauna or flora.

“The MTA will have to look at the environmental impact of any structures they might have to build like possible gantries if those are used to support license plate readers or EZ-Pass transponders, they will have to look at traffic and emissions impacts of the policy, impact on wildlife, they will have to document things like whether buildings of significant historic importance will be disturbed things like that,” said Regional Plan Association Senior Fellow Rachel Weinberger.

As the National Preservation Institute explains, there are no specific regulations saying what has to go into an environmental assessment, but it has to describe why an agency thinks a project is necessary, list alternative measures and detail the effects of those alternatives. The difference between an EA and a EIS is that in an environmental assessment, an agency has to determine whether or not a project will cross a threshold adversely effecting the people and region of a project. In an EIS, those effects have to be fully quantified.

An EA doesn’t have to explain every impact in detail, but agencies tend to treat an environmental assessment as kind of an “EIS Lite,” which can drag the process out and include conclusions on the impact of a project without explaining why an agency reached said conclusion.

As an example of a tolling environmental assessment similar to what the MTA may submit to the FHWA, in 2017, the federal agency gave a FONSI (“Ayyyyyy”) to a Rhode Island Department of Transportation proposal to install truck tolls on a stretch of I-95 in the state.

The Rhode Island DOT’s environmental assessment looked at various impacts that the installation of toll gantries themselves would have on groundwater or soil, but it also looked at broader implications of tolling, such as the potential economic impact of the tolls and how it could affect traffic on I-95 — which could be relevant to the upcoming congestion pricing EA.

For instance, the study looked at whether the toll — which the study assumed would be $3.50 to $4.50 — might encourage truckers to leave the highway and drive through local streets to avoid the fee. The study determined that they would not do so in any significant numbers, so, as a result, air quality would not significantly decline along the no-toll route, nor would trucks going around the toll have a significant impact on property taxes or pedestrian and cyclist activity along said free route.

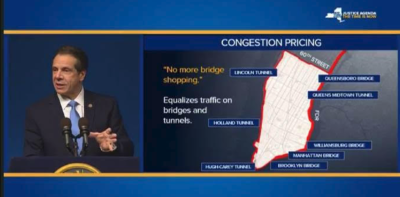

In the case of New York’s congesting pricing, that type of toll avoidance behavior will also be studied — both in terms of whether current car commuters would suddenly start riding transit more or whether they will begin driving to the edge of the congestion zone and looking for parking. But former NYC Traffic Commissioner and CEO of Sam Schwartz Engineering “Gridlock” Sam Schwartz said it was unlikely that tolls of, say, $15 would create negative impacts on local roads or the subway.

“It is not likely that there are significant impacts at the periphery,” said Schwartz. “People don’t fight the traffic for a long period of time [then look for] a parking spot, which is not easy in the periphery of the CBD.” He suggested that most drivers would quickly learn not to drive to the Upper East Side, where they would likely hunt for a spot for a half hour only to give up and put the car in a lot — then pay to ride the subway to their final destination.

Backing up Schwartz’s assertion is a study on residential parking permits that Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer released in 2019, which showed that there was no evidence of a large numbers of drivers engaging in the behavior when London instituted congestion pricing in 2003.

Nonetheless, it will be studied anew in the EA.

“If the change is that suddenly more people in Astoria don’t drive across the Queensboro Bridge and take the N train, then the MTA would calculate how many people per hour that is, how many trains per hour spread it over the number of cars, the number of staircases [in stations],” Schwartz said.

If, contrary to what the MTA and advocates for congestion pricing have predicted, the FHWA does find that the project would have severe impact on geographic, environmental or social contexts, it could order up a full environmental impact statement. (If that happens, you can kiss goodbye to congestion pricing for a few years.)

On the other hand, if congestion pricing gets a FONSI (“Ayyyyyy”) from the feds, drivers may end up suing to force an environmental impact statement. Of course, it’s not just drivers who use this legal tactic; in Portland, a group of environmental advocates sued the federal government on the grounds that the FONSI for a highway expansion project in the Rose City violated federal environmental law because serious impacts of the project were not considered by the EA.

Such a suit seems likely in New York — after all, this is a city where attorneys sued to block a busway on the grounds that a transit improvement would have a negative environmental impact, so there’s always the possibility that congestion pricing gets tied up in the courts.

The public comment period will, of course, reveal its own challenges and complaints, some of which is already happening in the form of Assembly Member David Weprin’s cheap pandering to delay the project or a pair of New Jersey members of Congress who are demanding residents of their states not pay additional money to pollute New York City streets.

There is literally a toll bridge in the picture, Congressmen. There is nothing new about tolling drivers to go certain places. https://t.co/T1KMVlAEHl

— Streetsblog New York (@StreetsblogNYC) April 9, 2021

The bellyaching could affect who gets exemptions, beyond the law’s handful of allowances already. The Rhode Island DOT environmental assessment determined that there were no low-income or minority populations that would have been effected by instituting or not instituting the truck tolls. In the case of congestion pricing, the only income-based exemption at the moment is a tax credit for residents of the CBD who make less than $60,000 per year.

Although there will be calls to give low-income and middle class New Yorkers a break of some kind, an analysis by the Community Service Society found that “2 percent of the city’s outer-borough working poor could potentially pay a congestion fee as part of their daily commute. This compares with 58 percent who rely on public transit and would theoretically benefit from a congestion pricing plan that raises money for both improved transit services and fare discounts.”

Schwartz urged the MTA to hold fast on not granting free passes to drivers.

“Right now if you take the New Jersey Turnpike or the Garden State Parkway, and you take it to the George Washington Bridge, and you go over the Triboro, when you get to the George Washington Bridge, it doesn’t give you a discount because you already paid on the Jersey Turnpike. And the TBTA doesn’t give you a discount because you paid it to George and you paid at the New Jersey Turnpike,” he said.

For its part, MTA management has not shown any interest in delaying congestion pricing any more than it already has been, and are already signaling to the New Jersey Parking Delegation that there’s already a solution for their constituents to avoid paying a congestion toll.

“For anyone in New Jersey concerned about the possibility of tolls going up, they can also ride New Jersey Transit, which is a fabulous transit system,” said New York City Transit Interim President Sarah Feinberg.