ANALYSIS: So You Wanna Be New York City Mayor, Huh?

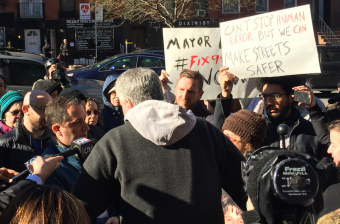

We asked candidates what they thought on a raft of street-safety issues. Here's what WE thought.

For the past two weeks, Streetsblog readers feasted on the seven posts we spun out from our mayoral candidate questionnaire. In them, we asked all 11 contenders — Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, former U.S. Housing Secretary Shaun Donovan, former Sanitation Commissioner Kathryn Garcia, entrepreneur Zach Iscol, Council Member Carlos Menchaca, non-profit executive Dianne Morales, Comptroller Scott Stringer, former Veterans Affairs Commissioner Loree Sutton, former Counsel to the Mayor Maya Wiley and crusading lawyer Isaac Wright, Jr. — what they plan to do about a raft of issues. (Financier Ray McGuire is the only mayoral candidate who did not respond.)

The previous posts asked the candidates on whether they would:

- Make permanent open streets and open restaurants

- Monetize all the “free” parking

- Make Manhattan car-free

- Rid the streets of reckless drivers

- Lessen the footprint of fossil-fuel interests

- Rein in the NYPD

- And move the city beyond Vision Zero into a car-independent era.

The stories gave the candidates ample space in which to explain their positions, without interjecting our analysis. (That was an act of mercy toward readers, given the candidates’ loooong answers. Next time, we’re going to impose a word limit!) But for the final punctuation mark on our series, we decided to summarize the candidates’ answers into key themes and takeaways — a one-stop-shopping approach to help voters narrow down their options:

Who really would rein in the cops?

This was a real litmus-test question, given the NYPD’s wholesale flouting of Mayor de Blasio’s authority.

A former cop, Adams did not stake out any bold reforms, saying that “you can’t take the police out of Vision Zero” and calling for “greater precinct-level accountability from integrity control officers.” Can’t take the police out of Vision Zero? Really? Street-safety activists, fed up with cops who don’t even know the rudiments of the Vehicle and Traffic Law and just use it to hector Black and brown people, are arguing for just that, in the form of beefed-up automated enforcement and moving other responsibilities to the Department of Transportation.

Donovan described himself as “sickened” by road deaths; Garcia said de Blasio had “lost control” of his own cops. “Sickened” and “lost control.” Those are good words.

Donovan inveighed at length against police abuses and identified several areas of traffic enforcement that he said were “ripe for removal of NYPD presence,” including crowd control, street-vendor enforcement and “run-of-the-mill vehicle stops.”

Sutton (who’s also a psychiatrist and a former brigadier general) offered a “strategic framework for reimagining modern policing, reinvesting in communities and police officers as partners in public safety and rebuilding trust through collaboration,” which sounded like a group-therapy session for a city agency that’s not prone to navel-gazing.

Iscol professed himself a fan of Transportation Alternatives’s report “The Case for Self-Enforcing Streets” (a Baedecker for using safe-street design to get cops out of enforcement), as did Stringer, without mentioning the document. OK, but the responses sounded a bit rote. Menchaca, Morales, Wiley and Wright set the question into the larger one of social justice, but did not sketch out their ideas in any detail. (In fact, Wiley’s responses to all of our questions were notably thin for someone who considers herself a top-tier candidate. Wright gets a pass on substance given that he’s a recent entrant to the race; we held open the questionnaire for a few days in order to accommodate him.)

So the jury is out on the question, but we don’t think former Captain Adams will significantly alter the NYPD. One thing is clear: A Mayor Isaac Wright would demand that the NYPD change its strategy on arresting food vendors.

“I love churros,” he said in response to our question. “That’s not exactly pertinent to the question on hand, but I’d like to go on record with that. This is a pro-churro campaign.”

Who is most serious about a car-free Manhattan?

The most enthusiastic proponents of our flat-ban proposal (“Do you support a ban on private cars in Manhattan — and if not, why not?”) were Menchaca, Stringer and Sutton — all of whom said some species of “yes.” Morales said she supported the “vision, but not an outright and immediate ban,” and placed the question of cars in the context of social equity.

Donovan said “a fully private-car-free Manhattan isn’t feasible,” but said he would press for more bus and bike lanes, better curbside uses, and transit to reduce unnecessary car trips.

Wiley would give her proposed “People’s Assemblies” (which sound like community boards on steroids) a voice in the matter.

Iscol flat out punted, saying “no” to a private-car ban in Manhattan. He cited pandemic recovery considerations and the fact that “many people that have never commuted by car [but] are now doing so out of concern for their and their fellow New Yorkers’ health.” That was a weird answer, given that real leadership means steering the ship of state towards a desired destination, not watching it steam ahead into an iceberg.

Who really understands that street-safety questions are about justice and equity?

There was broad agreement among the candidates that better transit — especially faster buses, in their own lanes — and safe bike and pedestrian infrastructure are crucial to building a fairer and more equitable city. We should stop for a moment and marvel: The fact that these positions have emerged as the de-facto platform of progressive politicians stands as a signal achievement of the safe-streets movement, which agitated and protested and organized in order to make it so.

“I recognize the inherent racism in our current car-culture, the highways that bifurcate neighborhoods and the racial disparity of injury in vehicle strikes,” said Morales (an acute analyst of racial and class disparities, as well as the unintended consequences of some well-meaning reforms, such as parking permits).

Morales and Garcia both noted the depredations of truck traffic on many communities, especially those of color. Garcia touted that she “led a comprehensive and widely supported reform of the private carting industry that will slash truck travel and create safer streets for both industry workers and the public.”

Wright and Wiley said eloquent things, but didn’t display much policy heft.

Adams did some neat equity addition. He pointed out that “underneath the 700 miles of elevated bridges, highways, subway and rail lines lies millions of square feet of public space — nearly four times the size of Central Park.” He proposed “activating it for community art, bicycle superhighways, open space, bus rapid transit and simply to combat the psychological barriers that disconnect us from our neighbors even though they may just be a block away.”

Donovan felt so strongly that transportation “has to be in your top three” of issues for building a fairer city that he gave Streetsblog an exclusive on his transportation plan separate from the mayoral questionnaire.

Menchaca sought a role for law: “I am supporting fully funding the Reckless Drivers Accountability Act, and have criticized the de Blasio administration for not fully funding it in the last budget, almost voting the entire budget down for diluting this essential program to get reckless drivers off from our streets. During de Blasio’s first term I also supported the Right of Way law, which made it a misdemeanor punishable by up to 30 days in jail to injure or kill a pedestrian or cyclist who had the right of way.

“The truth is that this work is just beginning,” he continued. “The city must do more to make sure that pedestrians and cyclists have good city infrastructure, and that bad drivers cannot haul vehicles around our streets endangering innocent lives.”

Who really has the desire — and mojo — to take on the car lobby?

A number of the candidates talked the talk here.

Sutton: “I strongly support efforts to transition from a car-dominant culture to one that encompasses fewer vehicles fueled by fossil fuel, safer and more inviting spaces, thoroughfares for buses, for hire vehicles, bikes and scooters as well as pedestrian passageways. This desired outcome will not happen on its own or by elected officials alone — it will require leadership and transparency at all levels.”

Donovan: “I will get the Verrazzano Bridge opened for pedestrians and cyclists, implement an upgrade to the Brooklyn Bridge pedestrian and cycling path, study road use for bikes on the 59th Street bridge, build a protected bike lane in Astoria between the 59th Street and Triboro bridges, and improve bridge crossings between the Bronx and northern Manhattan. Putting paint on the asphalt and calling it a bike lane is unsafe for cyclists and another example of toothless policy that prioritizes cars.”

Menchaca: “I support metering all of the city’s free parking spaces. These three million parking spaces represent a huge portion of public land set aside for only a small segment of the public — car owners — many who come from out of the five boroughs. Metering these spaces at a fair rate, and dedicating this money towards MTA improvements would allow this public land to truly benefit the entire public. It would also remove the undue burden on working people who have had to consistently pay fare hikes to support the city’s train and bus system.”

Who really gets open streets and open restaurants and understands how thoroughly we must reform curbside uses?

All of the candidates approved of making open streets and restaurants permanent, but a couple put meat on the bones of exciting ideas for curbside uses.

See, for example, Menchaca’s plan above for universal metering. He has since floated a plan to eliminate at least a million parking spaces.

Donovan advocated for centralized trash collection, at least in certain places: “There has to be a better way than the walls of trash in front of large residential buildings that block our sidewalks,” he said.

Stringer said that “priority no. 1 is repurposing curb and street space for pedestrians, bikes, buses, strollers, wheelchairs, restaurants, retail, and various public uses.”

A number mentioned loading zones and the need to accommodate new kinds of trade and transit.

Stringer and Garcia, for their part, said that they would explore residential parking permits; it’s not clear that those would discourage car ownership or would amount to much more than “hunting licenses” for an entitled minority of car owners. Stringer earlier has proposed some intriguing ideas for street safety (notably, his plan to put 75 miles of protected bike lanes around 50 high schools), but this was a blooper. Other Stringer responses seemed kind of flat, but we know him to be a leading candidate on these issues.

Finally, who best understands how to prod the dumb beast of city government to do what must be done for safe streets?

Let’s be blunt: Political considerations aside, New York mayor is not an entry-level government job. It helps to have worked in city government (or attended a four-hour community board meeting about removing three parking spaces) in order to understand just how f—ed it can be. (Full disclosure: I worked for two city agencies in press roles.)

Despite the efforts of the last few mayors, some bureaucracies lack digital acumen (and often raw computing power) and cling to old-fashioned methods of administration. Municipal unions basically “own” many bureaucracies or large parts of them. One needs a clear-eyed appreciation of these arrangements and limitations and a nimbleness in order to navigate them. Managerial experience helps enormously (the current mayor, for example, demonstrates how ill-suited the skill set of a longtime political operative is for the task), as do the contacts and relationships for attracting and evaluating top-flight talent.

So it’s heartening to see many candidates with substantial city government experience vying to lead us. Two are independently elected officials; three headed departments (in one case, both a city and two federal ones); one is a lawmaker and another was a mayoral adviser. That showed in the candidates’ answers to our questions: Those with experience in the belly of the beast, especially managerial experience, offered richer solutions. Go back and read them all at the links below:

- The candidates on open streets

- The candidates on “free” parking

- The candidates on Manhattan car-free

- The candidates on ridding the streets of reckless drivers

- The candidates on lessening the footprint of fossil-fuel interests

- The candidates on reining in the NYPD

- The candidates on moving the city beyond Vision Zero into a car-independent era.