THE DONOVAN PLATFORM: Better Transportation Can Make the City Fairer, Greener and Safer

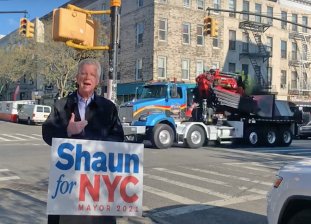

Buses and bikes — that’s the key to a better, safer and more equitable city, according to mayoral candidate Shaun Donovan.

Firing what is basically the first transportation salvo in a mayor’s race that is currently dominated by other issues, the city (and nation’s) former top housing official has outlined what he calls a vision for a “21st-century transportation system that improves transit service for everyone, prioritizes mobility expansion in underserved areas, makes the streets safe for everyone who uses them, combats climate change, and reverses the legacy of racism within the city’s current transportation network.”

When it comes to transportation, the devil is not merely in the details, but in the delivery. No one put Vision Zero at the centerpiece of his agenda like Bill de Blasio — it was literally his first initiative after taking office in 2014 — but many advocates say that beyond setting that lofty agenda, the mayor didn’t consistently fight the war on cars. In an interview, Donovan said his plan is more than just an agenda, but a calling.

“Transportation has to be on your top three list,” he told Streetsblog this week. “This issue is at the center. Look at the first line of the platform: ‘Transportation is the central nervous system of the city.’ I fundamentally understand that if people are not connected and they can’t stay alive as they walk around, they cannot get access to opportunity in this city. That’s why I am leading with this.”

How far does Donovan’s plan go? It’s built on several pillars:

- Creating “true bus rapid transit.”

- Truly embracing cycling and micromobility by broadening access and safety.

- Making roadways safe from reckless drivers.

- Oh, and legalizing marijuana.

On that last one, Donovan strongly threw his support to legalizing the sale of pot — which the state legislature could then tax. But Donovan would only devote some (not all!) of that expected $500- to $750-million windfall to transit.

“A portion of that money could be set aside for public transit improvements and this could be bonded to support capital expenditures,” Donovan says in the platform. “Given other states’ movements towards legalization of marijuana, New York should go next.”

The ganja tax would be out of Mayor Donovan’s hands anyway because it would require approval by our higher leaders in Albany, so the platform mainly focuses on areas that a big city mayor can actually control:

Better bus service

Donovan’s plan calls for “true bus rapid transit,” but does not put a lot of meat on that bone. After stating the fact — “Buses in New York are slow and unreliable for those who need them the most, and the city has not worked aggressively enough to prioritize bus transit systems” — Donovan adds only that “the city should prioritize investment in a true Bus Rapid Transit System in key corridors with dedicated right of ways, intersection treatments, and stations while also improving regular bus service.”

Specifics? Donovan calls for the city to implement the MTA’s early-pandemic demand for 60 miles of dedicated bus lanes (which Mayor de Blasio answered with a promise to build 20 miles of dedicated bus lanes, then struggled to fulfill even that). City law already requires the construction of 30 miles of dedicated bus lanes every year, starting with the next mayor.

In an interview, Donovan went further, saying he “would appoint a chief equity officer reporting directly to the mayor because every issue is an equity issue — you have to have a screen that says, ‘Where are the areas that need this?'”

He also claimed, perhaps with accuracy, to be “the only candidate running who has been to Curitiba,” a reference to the Brazilian city that is celebrated for two things: its weather and its bus rapid transit.

A true “bus rapid transit” system is a heavy lift that requires repurposing road lanes or entire roadways from cars and giving them over to buses, often in lanes secured by concrete — a commitment Donovan repeated to Streetsblog. Such configurations are virtually non-existent in New York City (though the DOT recently built a modified version in The Bronx), but are popular all over the world, where transit riders truly get priority over drivers. “True” bus rapid transit also includes dedicated passenger waiting zones and all-door boarding that treats a bus more like a subway.

Such a system in Jakarta, Indonesia, for example, carries more than 1 million passengers a day — roughly half New York’s typical daily bus ridership. So a “true” bus rapid transit system in New York would mean doubling the capacity of the world’s biggest BRT system — no small job.

Donovan’s plan also calls for equitable expansion of bus lane camera enforcement — so clearly not all buses are going to get their own car-free roadways.

But responding to a follow-up question, the Donovan campaign said, “We aren’t talking one corridor, we are talking multiple lines that can support effective transport.”

Cycling and micro-mobility

On cycling, Donovan doesn’t throw out any big, Streetsblog-headline-grabbing numbers, but he does lay out the facts (and failures) of the de Blasio years:

“Though there are more than 1,200 miles of bike lanes currently across the five boroughs, only 480 miles of them are protected,” he writes, adding that “more people were killed [in 2020] in traffic than in 2019.”

“People dying in the crosswalk is not an unavoidable part of city living,” he adds.

What’s the solution? Make cycling safer. “Two-thirds of commuters who don’t bike cite safety concerns as their primary reason for not biking,” Donovan accurately states, saying he would champion a more connected bike network to replace the “fragmented bike lanes” we currently have. “Cycling and micro-mobility are important and growing modes of transportation, the city lacks the infrastructure to support these alternatives as true choices for many drivers.”

But a hard number of new protected bike lanes? Donovan does not lay out a vision, suggesting that he is satisfied with the 50 miles of protected bike lanes that will be required of the next mayor under the Streets Master Plan bill signed into law last year by Mayor de Blasio to take affect in the last month of his administration.

“The issue is to create connectivity, a true bike network on par with the world’s great cycling cities,” Donovan said in the follow-up interview. “But paint is not a sufficient substitute for true protected lanes.”

Donovan, who is a regular cyclist and subway rider, also said he supports the city’s e-scooter pilot proposal, but would ensure it is equitable.

“The city must ensure that safety, choice, equity, and transparency are key pillars of any introduction of private sector operators,” he says. “E-scooter companies operating in the outer boroughs should be responsive to community needs.”

Road safety

Donovan clearly believes that Vision Zero has not gone far enough.

“We need to put people, not cars, at the center of all transportation conversations and projects,” he says, citing a commitment to “improve street design, get reckless, unsafe drivers off our streets, and reduce illegal speeding by cars and trucks.” That’s exactly the kind of sentence that could easily have been plucked from Mayor de Blasio’s first Vision Zero press release in 2013, but Donovan says he will go further.

“Vision Zero only scratches the surface of what is needed — a comprehensive plan with a series of policy changes that is laser-focused on all New Yorkers safety and security and an overhaul of the program is critical,” he writes. “We are committed to lead the effort to reimagine the city’s streetscape, reduce the city’s reliance on cars, expand bus and bike lanes, and end traffic violence.”

Streetsblog was surprised that there was nothing in the Donovan plan about the role of the NYPD, whose policing of public space has come under consistent fire from communities of color, and whose consistent failure to properly investigate crashes remains a source of pain to crash victims. The agency’s willfully under-staffed Collision Investigation Squad only examines a tiny fraction of the more than 250,000 crashes every year — and its analyses of the most serious crashes does not inform the decision-making process at DOT, which Streetsblog has criticized.

So we asked for — and got — more details from the campaign:

Vision Zero, the concept that through engineering, education and enforcement New York City can promote mobility, safety and public health while simultaneously eliminating traffic fatalities and injuries, must be an essential component of New York City’s approach to transportation projects, street design, and city planning in general. We can implement effective elements of Complete and Green Streets and introduce evidence-based policies that promote safety, such as self-enforcing streets that use fair, predictable, technology-based enforcement to reduce unsafe driving; move traffic enforcement (including the Collision Investigation Squad) from the NYPD to DOT; hold unsafe and reckless drivers to account and keep them off our streets; and improve safety standards and practices within the city’s fleet of vehicles.

Donovan himself added, “If we can get our streets designed properly, that solves a lot of problems.”

Conclusion

There are some holes in the Donovan proposal, which says nothing about parking (though the candidate did address “free” parking in an earlier Streetsblog piece). And the proposal does not explicitly discuss reducing the sheer size of the city’s own vehicle fleet, which actually increased in size during the mayor’s term before finally starting to shrink.

But whatever its deficiencies, Donovan’s plan talks the talk on key concerns of livable streets activists, and stakes out territory that has thus far been ignored by all his challengers with the exception of Scott Stringer (here and here), Carlos Menchaca (here and here) and Kathryn Garcia, who has posted a detailed transportation policy on her campaign website. He is clear on the danger of cars, such as pollution, road violence and congestion.

“We must get people out of their cars and into other modes of transportation that will improve the health and resilience of the city,” he says. “By connecting bike lanes with current transportation hubs, we can reduce our reliance on cars and work to lower the emissions coming from private vehicles.”

And Donovan also clearly supports congestion pricing, the city’s open streets program and the city’s innovative reuse of curbside space during the COVID era. And he would fight for pie-in-the-sky ideas such as more city oversight of the MTA and a new partnership among the city, state and feds to properly finance transit.

And, like Bill “Tale of Two Cities” de Blasio, Donovan believes that inequities in transportation are like the hidden racism that few openly talk about.

“We cannot be one city without acknowledging and understanding how many communities suffer from the legacy of racism in transportation decision-making,” he says, citing underinvestment that has reduced transportation options in “communities of color and low-income neighborhoods.”

“We commit to rethinking investment decisions by deploying data and tools to make sure often ignored communities get real transportation benefits and services,” he says.

Street safety advocates were cautiously optimistic — and hoped Donovan’s platform on transportation would encourage other candidates to address the issue broadly.

“New York City needs leaders who will prioritize people over cars,” said Danny Harris, the executive director of Transportation Alternatives. “To do so, they must build out a stronger network of busways and protected bike lanes, make open streets permanent and more equitable, and bring a heightened focus to ending traffic violence. We are looking forward to having important conversations with candidates and communities citywide over the coming months to ensure these transportation priorities, and many others, are brought to the table in 2021 and beyond.”

Bike NY spokesman Jon Orcutt, who also worked in the Bloomberg administration, albeit at DOT, said he was please “to see bike lane design mentioned here, because the city’s definition of ‘protected bike lane’ seems to become more suspect each year.”

This is the first in a series where 2021 mayoral candidates reveal their transportation platforms to Streetsblog, which will then present them in, as you can see, lengthy, detailed form. We encourage all candidates to participate by emailing Streetsblog Editor Gersh Kuntzman at gersh@streetsblog.org.