Hear What Black and Brown New Yorkers Think About Bike Infrastructure

For all the talk about making New York City more bike friendly, there is very little emphasis on anything besides safety. Protected bike lanes are, of course, critical to luring more people onto environmentally friendly bicycles and scooters, but any plan that focuses solely on this element would be terribly incomplete.

Instead we must consider the full experience of using a bike in New York and all pain points that come along with it. What good is a network of safe parking lanes, for example, if it’s impossible to find a bike mechanic for an urgent fix?

For the past three years, I’ve focused on an especially important and neglected part of the cycling ecosystem; secure bike parking.

Working through Oonee, the company that I co-founded, to build a network of accessible secure bike parking facilities across the metropolitan area. Aside from safety, bike parking stands out as the other major pain point for New York’s riders. Bike theft is rampant and bikes left on the street overnight are often vandalized or damaged by the weather. Simply put there are many thousands of people who would love to bike more often but simply lack convenient storage options.

Unfortunately, the Department of Transportation simply does not consider bike parking to be a priority. Having quietly shelved its own secure bike parking pilot, the DOT continues to erect roadblocks that would allow for even basic private solutions like Oonee quickly fill this void. The city won’t spend public dollars on a network of facilities or allow private operators to take advantage of advertising and sponsorship to offset the costs either. Aside from our facility in Downtown Brooklyn, New York City has no affordable public facilities for bike parking.

At the core of this institutional reticence is the internalized belief that bikes and scooters are mostly a novel form of transportation that is electively utilized by mostly White, affluent New Yorkers. This misbegotten narrative, often peddled on the pages of local media outlets, rests on the erasure of a vast population working cyclists who mainly hail from communities of color.

In fact, communities of color and immigrants are actually more likely to rely on their bikes for transportation, work and commuting than their white counterparts. Our city’s restaurant and delivery ecosystem actually is built upon this truth, so much so that workers on bikes were broadly recognized as “essential” during the darkest days of the pandemic.

Working cyclists and communities of color are more likely to need their bikes for work, less likely to have access to secure parking at their workplace, and far less likely to be able to replace their bike if stolen.

For these New Yorkers, secure bike parking isn’t a “nice to have,” it’s a must.

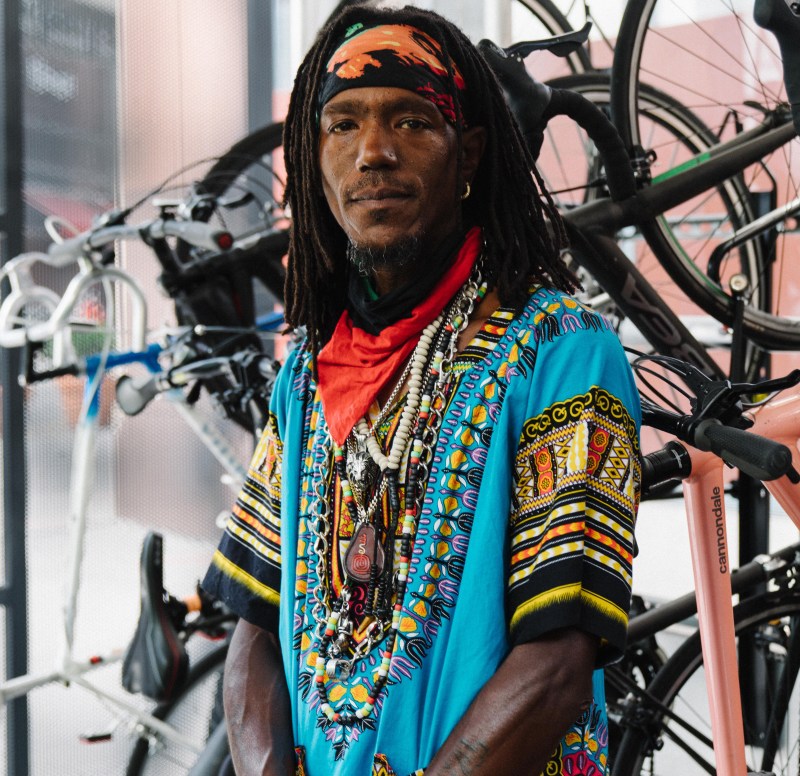

Kawan Taylor, the first of our “Oonee perspectives” series, brings this truth to life by explaining how a simple secure bike parking facility changed his life.

Taylor, like 61,000 other New Yorkers, lives within the city’s sprawling homeless shelter system. For Taylor, earning and saving money by making essential food deliveries is a means of upward mobility; he plans to use his savings to get a place of his own in the near future.

Since Taylor isn’t allowed to keep a bike or scooter at his Chinatown shelter he makes a daily commute to Oonee’s secure bike parking facility at Atlantic Terminal in Downtown Brooklyn, where he is able to park overnight for free. While he’d love to have a closer facility, the DOT won’t permit any other stations in Lower Manhattan.

Like many working cyclists, Taylor has had multiple bikes stolen, and finding a replacement can easily amount to a week or more of wages. For him this is an issue of economic survival, so he has no choice but to make the journey each morning.

Today, we’re sharing Kawan Taylor’s story, but in the coming days we’ll be sharing six other perspectives on Medium and social media. (You can find us @ooneepod on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.)

During the course of the week, we will share the perspectives of six other New Yorkers, all hailing from the city’s Black and brown neighborhoods, on the importance of building an inclusive system of cycling infrastructure that app. (Posts can be found on our Medium page, and will be announced daily on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.)

In their own way, each of these stories will address the crucial importance of bike parking infrastructure to their lives as New Yorkers who bike. I hope Mayor de Blasio and DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg listen to their voices, as they work to fulfill their promise to build the fairest city in America.

Shabazz Stuart is the founder and CEO of Oonee. You can follow him on Twitter @shabazzstuart.

Author’s note: This series is made possible by an in-kind donation from Kel Bush, who is a local videographer and photographer. Please consider using him for your upcoming photo or video needs. You can contact him via his website at kelbush.com.