Op-Ed: City Must Include Street Vendors in Any Outdoor Dining Push

How the 'al fresco' movement could help under-served — and often harassed — immigrant-owned businesses.

The “al fresco” movement — which would open streets and sidewalks for “socially distanced” dining during the pandemic — provides the city with an unprecedented opportunity to do justice by the vendors who serve fresh and affordable food outdoors.

Street vendors, who for decades have fought official harassment for the right to operate their businesses, must play a central role in any city effort to extend street and sidewalk dining.

It’s simply a matter of equity: The city already has passed legislation to support brick-and-mortar small businesses, including waiving sidewalk-licensing fees, but it has not afforded street vendors any relief. Mayor de Blasio has ignored calls from Council members to forgive outstanding fines issued to vendors and to suspend enforcement of street-vendor compliance unrelated to public health.

In fact, city harassment of vendors continues: On Sunday, police ticketed three vendors in Corona Plaza in Queens who were merely selling food in order to get money to feed their own families.

Such harassment, unfortunately, is nothing new — but is especially tragic in the teeth of the pandemic. Some 20,000 New Yorkers — the vast majority of them low-wage immigrant workers and people of color — sell food and merchandise from the streets and sidewalks, relying on busy streets in order to survive. Most are reporting income losses of 70 to 90 percent.

Take, for example, Gregoria, a Corona Plaza vendor. “I’ve worked today from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., and I’ve made $7,” she told us last week. “People who walk by are scolding me for working and trying to make me feel guilty for being outside, but what they don’t understand is that I have to work, I can’t stop working and be inside like everyone else. My husband’s hours were cut. We have five children at home, and he now has to stay with them because they’re out of school and I have to be working. There’s no childcare or support for undocumented people like me. We don’t know what to do or how we’ll keep going.”

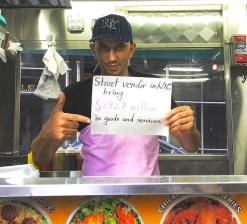

She’s not alone. As small-business owners and workers, street vendors contribute about $293 million to the city’s economy. Yet despite their critical role, they often are excluded from disaster relief, whether because of their immigration status or the informal nature of their work.

Vendors struggle with an unjust regulatory system that penalizes them with fines for setting up near a bus stop, a building entrance, too far from the curb, or selling in one of hundreds of restricted streets. Rather than acknowledging the important role that street vendors play in our city’s culture and economy, the system criminalizes mothers, fathers, and immigrant entrepreneurs for “crimes” such as selling $1 churros. Such enforcement can lead to property confiscation or even arrest. Vendors never get the benefit of the doubt compared to more “legitimate” business interests.

So what can the city do?

The first, and most overdue, the mayor could lift the cap on vending permits and licenses, automatically creating (or legalizing) thousands of jobs for mostly low-wage immigrant New Yorkers to provide meals to New Yorkers in socially-distanced outdoor settings.

@NYPD110Pct is criminalizing Corona Plaza vendors who must work to feed their families. Tonight they cruelly gave tickets to 3 members of the Corona, Queens community for vending without a license. @CatalinaCruzNY @jessicaramos @AOC @FranciscoMoyaNY @chrisychung @TanayWarerkar pic.twitter.com/zOzwxJLstx

— Street Vendor Project (@VendorPower) May 19, 2020

The city could also look to the street-fair model, enabling vendors with easily obtainable temporary permits to serve food to the public. That would allow the city to limit the number and density of vendors in order to accommodate social distancing, just as farmers markets have adapted their layouts to continue operations during the public-health crisis.

Open streets might also allow the city to extend vending opportunities in the roadway — adding food carts to the food trucks that operate there now, along with some adjacent seating, a practice common in cities around the world.

Finally, the city could repeal the Department of Transportation’s decades-old (and hopelessly outdated) regulation prohibiting food trucks from metered parking spaces, which renders almost all spots off-limits for such trucks.

Immigrant street vendors from Corona, Queens fined for selling tamales & flowers, yet excluded from city, state, and federal relief in the center of the #COVID19 epidemic. The #NYC sanctuary city lie has never been clearer. pic.twitter.com/IuaZgZ3D7G

— Street Vendor Project (@VendorPower) May 19, 2020

We applaud the city’s initiative to open more streets for social distancing, simultaneously supporting restaurants by extending street-seating options. We should not forget, however, that vendors have been fighting for years for the right to operate in our city’s streets. Unless the city explicitly includes street vendors in all plans, the unequal history of enforcement of our public streets will continue, and vendors, who come from communities that have suffered disproportionately during the pandemic, will remain excluded from recovery efforts.

The Street Vendor Project (@vendorpower), a membership-based organization that is part of the Urban Justice Center, works to defend the rights and improve the working conditions of the 20,000 people who sell food and merchandise on city streets.