The MTA Needs More Money. Will It Get It?

“Cash-strapped” is not just a cute adjective that always precedes the noun “MTA.” It’s a harsh reality.

Just as subway and bus service is finally improving, and the MTA is preparing to make massive, long-term repairs paid for with congestion pricing, the regional transit agency is facing a cash crunch so severe that service cuts now seem inevitable — and they’d come exactly at the worst possible time, advocates and elected officials are warning.

Speaking to a crowd at a TransitCenter event last Tuesday night, Assembly Member Amy Paulin laid out a dark scenario for bus and subway riders. Paulin noted that the MTA was expected to borrow money for both the 2015-2019 capital plan and the upcoming 2020-2024 capital plan, and that borrowing costs eat into the MTA’s operating budget.

“There’s still going to be a gap,” Paulin said about the funding formula for the upcoming $51-billion capital plan. “That gap is important for us to reckon with because in order to borrow money, you have to pay the cost of that borrowing, and that’s in the annual operating fund. To borrow all of that money, we have to pay attention to the deficit it’s going to cause in the operating budget. And that deficit is going to have to be realized by perhaps sacrifices going forward.”

How did we get here?

The MTA has a shiny new funding toy in congestion pricing and other new taxes, but the $25 billion that will be raised will only help pay for work on the agency’s capital spending side. So while the 2020-2024 capital plan will have the kind of dedicated funding necessary to do things like resignal huge parts of the system, install accessibility upgrades and finish another incredibly expensive leg of the Second Avenue Subway, there’s less and less money available to actually run transit service.

The MTA’s operating budget deficit is large, and is only slated to get larger. Earlier this summer, Rachael Fauss and John Kaehny of Reinvent Albany called the agency “fiscally exhausted.” Based on the MTA’s own data, the total amount required just to service the underlying debt will rise to $3.22 billion by 2022 — a year when the entire operating budget deficit is projected to hit $976 million. And those projections came before the MTA announced it would hire 500 new police officers in an attempt to deal with homeless individuals living in the subway system.

That hiring spree will not help matters, according to the Citizens Budget Commission.

“Over the 2020-2023 financial plan, the cost of the 581 officers and supervisors will exceed $260 million,” the budget watchdogs wrote. “This amount combined with the MTA’s currently projected cumulative financial plan deficit of $740 million results in a $1-billion operating budget gap over the next four years.”

Paulin’s talk about sacrifices is the latest sign that service cuts could be on their way. Speaking to reporters after a board meeting in August, MTA Chair Pat Foye told reporters, “We’re reviewing the possibility of new subway and bus service adjustments in the fall.” And at the end of September, the MTA announced that it would run fewer buses on the B46 route to save money, a service cut so blatant that the agency tried to spin as a positive on the grounds that it would reduce congestion along the line.

“Fewer vehicles on streets speaks for itself as a reduction in traffic,” MTA spokeswoman Amanda Kwan famously told the Daily News.

So it’ll have to be service cuts, right?

“I just don’t see what kind of alternatives we have,” said Paulin, who chairs the Assembly’s Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions, which oversees the MTA.

Beyond the new police personnel to fight homelessness, the East Side Access project will add an additional $200 million to the agency’s operating budget when (if) it’s finished. Paulin added that the ballyhooed AlixPartners plan to save up to $530 million per year by creating a leaner, meaner MTA II isn’t a guaranteed fix.

“We have a problem going forward, and we’re assuming that everything that the AlixPartners plan suggests is going to come to fruition and save the money that it’s targeted to,” Paulin said. “So there’s so many assumptions here that I am very, very concerned.”

Can cuts be stopped?

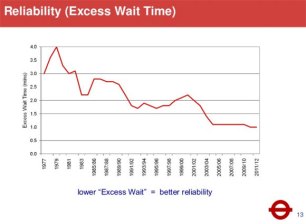

The prospect of service cuts has transit advocates on edge. If fully realized, the cuts could wreck a system that has barely begun crawling back to life after a period of declining ridership, and would no doubt decimate bus ridership even more than the system’s regular degradation has.

“The MTA has made great strides in providing better service over the last 18 months to two years,” Assembly Member Robert Carroll told Streetsblog. “So it would be unfortunate timing if finally as the subway is meeting much better on-time standards and having fewer breakdowns, and the MTA is having success with some of the bus redesign plans, this was coupled with service cuts that could mean less buses and subways for commuters throughout all five boroughs.”

Lisa Daglian of the MTA’s Permanent Citizens Advisory Council also said this is the last time for service cuts.

“It would be very unfortunate if the service reductions led to a death spiral that the system is just coming back from, from nine years ago,” Daglian said referencing the MTA’s 2010 service cuts that eliminated the V and W trains and almost two dozen bus routes. “There is service will never see again, and now there’s a sense of renewed focus and attention on improving our infrastructure and the way people get around.”

In an MTA analysis of the 2010 service cuts, cuts the agency instituted in the face of a $900-million deficit, the MTA determined that bus ridership fell by one percent and subway ridership increased by 0.3 percent as a result of bus riders taking subway alternatives. According to a report from Comptroller Tom DiNapoli’s office on the MTA’s finances, the agency forecasts subway ridership to decline “slightly” in 2019 compared to 2018, after three years of steadily falling ridership. The bus system has continued to hemorrhage riders though, with a 20.4 percent drop in ridership between 2008 and 2018.

Avoiding a death spiral then, where service is cut, ridership decreases, revenue drops and service is cut even further, could mean finding money for the MTA operating budget. Both Daglian and Carroll have ideas for how to raise revenue on the operating side. In a recent editorial she wrote with MTA Board member Andrew Albert, Daglian suggested ideas like raising the sales tax in MTA-served counties from .375 percent to .5 percent (which she said could raise $1.3 billion over five years) or changing the state gas tax from a per-gallon levy to a 4-percent fee per fill-up (which could bring in half-a-billion dollars, and even more if gas prices rise).

For his part, Carroll said that he felt the state legislature “wasn’t bold enough in our direct revenue for the MTA” last session. He referred back to some of his ideas from this past legislative session, such as a shipping fee on packages delivered by internet retailers and no longer allowing drivers who park in Manhattan garages to waive those garage taxes. Those proposals, according to Carroll, would raise $1 billion and $15 million per year, respectively.

Carroll also did say he was willing to find “smart savings” in areas like the ongoing Brooklyn bus network redesign.

Paulin said making a move for more MTA revenue need not be a political third rail, even in an election year (then again Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and State Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins did not respond to requests for comment). A spokesperson for Gov. Cuomo did not address the question of whether the state would raise more money for the MTA operating budget, and instead suggested the agency’s restructuring and an ongoing financial audit will save money.

“The state has committed billions of dollars towards both operating and capital needs for the MTA, but as part of the MTA reforms and restructuring they are required to conduct a forensic audit as well as implement a reorganization plan that will identify key savings to ensure the system continues to make progress and is as efficient as possible,” Patrick Muncie told Streetsblog.

Danny Pearlstein of the Riders Alliance said that it’s up to Como to champion additional operating budget revenue next legislative session, in the same way that the governor carried congestion pricing over the line in the spring of 2019.

“The governor drives the entire conversation around service cuts,” Pearlstein said. “He can steer it wherever he wants it to go. It’s up to Gov. Cuomo to decide what happens to transit.”

Service cuts, of course, not only drive riders away, but then lead to move service cuts as the MTA deals with the lost revenue at the farebox — unless the governor steps in. And he must, said Carroll, because service cuts hurt the most-vulnerable New Yorkers and leads to public alienation from the MTA in general.

“Across-the-board service cuts where we’re just running fewer buses as an hour, where we’re eliminating bus routes that are necessary but are maybe not as profitable as other routes, is just sending the absolute wrong message to everyday New Yorkers that the MTA doesn’t work for you,” said Carroll.