Four Lessons for 14th Street From Toronto’s Transit-First King Street

New York's Department of Transportation isn't completely following the lesson plan of Toronto's King Street — but just selecting a few items off the a la carte menu.

City officials are saying their “busway” plan for 14th Street was inspired by the success of a similar project on Toronto’s King Street.

But New York ain’t Canada.

In Toronto, city officials (and the city’s then-transit boss Andy Byford) saw the same problem that New York is now confronting: A key east-west artery and transit route was mired in congestion that was causing public transit to crawl and ridership to plummet. So Toronto went bold, banning cars and trucks from the byway, except for quick deliveries. All delivery vehicles were required to make the next legal turn — a solution that clear the congested roadway for transit (in this case a streetcar), whose ridership soared by 16 percent.

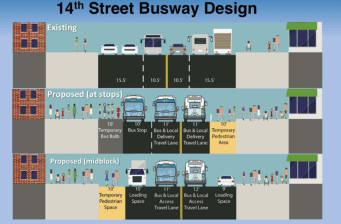

New York isn’t fully following the King Street lesson plan, but choosing items off the a-la-carte menu. For instance, where Toronto put dedicated loading zones, taxi stands, and 18 pedestrian plazas along its route, New York will use extra space for lanes with legal 30-minute parking — a near-guarantee of double-parking in a city already rife with scofflaw drivers.

And New York’s Department of Transportation will allow trucks to share the roadway with buses, a concession to West Village residents who were concerned that trucks would use more residential roads to get across town.

DOT’s L-train shutdown plan was more ambitious: Trucks weren’t allowed, and the design — which has already been partially installed — included painted sidewalks extensions that appear to have been nixed.

Select Bus Service and the accompanying transit priority restrictions won’t launch on 14th Street until June or so. Until then, the situation on 14th Street — featuring bumper-to-bumper traffic and unreliable buses — proves the need for change. The beginning of the L-train nights-and-weekends slowdown shows that 14th Street needs more robust bus service to weather the next 15 months. So here are four things NYC could learn from Toronto:

In New York, more shall pass

There is no other way to say it: New York officials caved to organized opposition on Manhattan’s West Side by allowing trucks to share an already limited roadway with buses. Streetsblog asked DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg about that on Wednesday, when the plan was first revealed.

“[On] King Street you had a pretty big commercial corridor and then a couple of somewhat large commercial corridors on the adjoining streets,” Trottenberg said. “Here, particularly over in the West Village, there was a lot of concern — and we didn’t want to discount it — that trucks would go … onto smaller more residential streets.”

As with highway removal projects across the world, Toronto’s effort on King Street didn’t lead to traffic armageddon on parallel streets. Traffic off King Street did increase, but the number of total cars in the overall area (including King Street) actually dropped by seven percent, according to data from the city of Toronto.

Another issue: cabs.

On King Street, for-hire vehicles are only permitted between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. — and that’s simply too much access even in a city with parallel commercial streets: On Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights, streetcar trip times are actually 30 percent longer — an ominous sign for NYC’s current plan to allow for-hire vehicles at all times.

New York will allow cabs all day and night — albeit for dropoffs and pickups only. Not even Trottenberg is certain that can work.

“We’ve done a lot of traffic modeling and the good news is, there isn’t a lot of pickup and drop-off activity,” Trottenberg claimed. “We have looked at taxi data and other things.”

And regarding her decision to allow through truck traffic, Trottenberg again was confident, perhaps overly so.

“It’ll be the local trucks that are serving this part of Manhattan,” she said. “We hope it will work well, but we’ll adjust it if we need to.”

Preventing back-ups at intersections

On 14th Street, drivers making local pick-ups or drop-offs and deliveries will have to make the first available right turn after they end up on the corridor.

In order keep buses moving, transportation officials need to make sure right-turning cars don’t get backed up in turn bays.

To boost traffic flow on King Street, Toronto gave drivers a head-start on pedestrians. That would be impossible to pull off on 14th Street, where the flow of crossing pedestrians barely stops for red lights. (Reminder: New Yorkers are different animals than Canadians, too.)

Giving drivers the lead over pedestrians is anathema in a walking city like New York. In fact, the DOT has spent the last few years improving safety by giving pedestrians a head-start over drivers, with a system called “leading pedestrian intervals.” But 14th Street will not succeed as a Select Bus Service route if all those cabs and cars making quick drop-offs or pickups get stuck waiting a full light cycle for pedestrians to pass.

DOT officials have said they plan to install right-turn bays at intersections, just as Toronto did on King Street, which would at least keep one or two cars out of the crosstown bus and truck flow — but that design could turn out to be insufficient if there are too many cars backing up at corners.

Consider what happens at every intersection in the city: pedestrians cross in front of cars. Even at low-volume intersections, a trickle of pedestrians keeps drivers from making turns. There is always a backup.

On 14th Street, the challenges are even more daunting due to extraordinarily high pedestrian volumes. Westbound drivers can make their first legal right turn off the busway on Irving Place (not a through street), but after that the next legal right turn is Sixth Avenue — which also happens to be one of 14th Street’s busiest in terms of pedestrians.

Camera enforcement: DOT’s secret weapon?

Enforcement on King Street has been imperfect. Here’s the scene on a typical Saturday night:

Let’s talk about the rules of the road in Toronto and the absolute lack of their enforcement. This has gotten beyond ridiculous. @Torontopolice can we do whatever the hell we want on the road? Because that’s what it looks like. This is embarrassing. #KingStreetPilot @joe_cressy pic.twitter.com/EIh2i3kNc1

— Pedro Marques (@MetroManTO) April 1, 2018

Still, the transit priority initiative worked well enough for the Toronto city council to vote 22 to 3 to make it permanent. That was in part because the regulations discouraged drivers from going anywhere near the street.

NYC is hoping for a similar outcome.

“The idea is to create regulations that you wouldn’t want to be there unless you’re doing a very local activity,” DOT Deputy Commissioner Eric Beaton told reporters last week. “If you are a passenger car, you can pick up or drop off, but because you have to make that next right turn, we don’t think it’s going to be attractive for anything except that very local access.”

Beaton and company also have a secret weapon: automated enforcement cameras, set to go online 60 days after M14 Select Bus Service launches — probably in June.

Until then, bus riders’ trips will depend on the NYPD, whose track record at traffic enforcement is less-than-stellar. As Streetsblog has documented, cops are some of the city’s worst bus lane offenders.

Cameras are certain to do a better job than NYPD personnel — Andy Byford has said as much — but they’ve been hindered by their limited presence. At the end of 2017, the city had only 94 cameras on 10 SBS routes, according to Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office. There’s going to need to be a much higher volume if they’re going to work on 14th Street.

Disregard the haters

Just as on 14th Street, transit priority efforts on King Street attracted opposition. In Toronto’s case, the loudest voices have been King Street’s merchants. One in particular, Al Carbone of Kit Kat Italian Bar & Grill, has taken an unorthodox approach to his activism: putting a giant middle finger outside his restaurant and running unsuccessfully for city council.

Carbone and his supporters even played hockey in the street to show how little traffic there was — totally unironically.

“The streets are empty. We’re trying to make a point that it’s empty — so empty and such a ghost town that we can play road hockey,” Carbone told Global News.

For the most part, Toronto officials have ignored Carbone and his allies. They’ve also countered the contention that the transit pilot hurt business with data showing that credit card purchases along the corridor have stayed steady.

Compare that to NYC, where even City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, who positions himself as a champion of mass transit, kowtows to the concerns of a loud cadre of opponents. In his statement following last week’s 14th Street announcement, Johnson would only give tacit support for the busway — contingent on proof that it is not having negative impacts on nearby residential streets.

If transit riders are going to see the best possible results on 14th Street, DOT — and Johnson — have to be willing to put transit first and let the unsubstantiated complaints fall to the wind.

If not, the miracle of King Street will stay in Toronto.