The Uber-Lyft Cap Has Nothing to Do With the L Train Shutdown

Lyft is using fear of the L train shutdown to score points against the City Council's proposed cap on ride-hailing fleets.

The City Council’s proposed one-year cap on licenses for Uber and Lyft has no bearing whatsoever on the looming L train shutdown. But that didn’t stop Lyft from organizing a cynical press event today where North Brooklyn business owners said the cap would make life miserable for them while the L is out of commission.

North Brooklyn businesses fear the impact of the 15-month L shutdown on their bottom lines for good reason — it cuts off a connection to Manhattan that carries hundreds of thousands of people each day.

Lyft is using those fears to its advantage. Anxious to fend off the limits on its fleet that legislation sponsored by Council Member Steve Levin would impose, Lyft organized a gathering of North Brooklyn business groups today to implore Levin and his colleagues to nix the cap.

Uber and Lyft, however, are no substitute for a train. The only feasible way to mitigate the disruption is to clear the streets of traffic so high-capacity buses can run as quickly and reliably as possible. Lyft and Uber drivers cruising for fares and gumming up bus service is a bigger threat to North Brooklyn than a potential cap on vehicles.

The business leaders who spoke today on behalf of Lyft haven’t absorbed that.

“Because our city has a robust network of transit, ride-share, bike-share, ferries and more, we were hopeful we could adapt,” said North Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce Chair Elaine Brodsky. “But if the City Council institutes this cap and reduction on ride-share, that possibility disappears. Overnight, North Brooklyn will become a transit desert.”

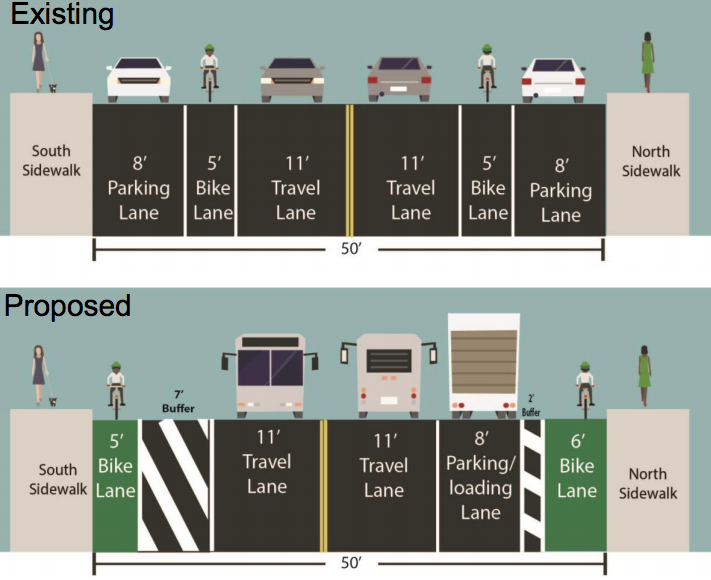

When the L goes offline west of Bedford Avenue next April, the MTA plans to run 80 buses an hour over the Williamsburg Bridge at peak times. To keep those buses moving, DOT will restrict the bridge to vehicles with three or more passengers and install bus lanes on streets approaching the bridge.

Lyft’s argument is that the cap will result in fewer for-hire vehicles on city streets, since the company’s employee attrition rate is 25 percent. The company referred to the L train shutdown in an action alert sent to users of its app last night:

A blanket UberLyft cap may be too blunt an instrument but these emails to rile up the base are full of exaggerations and lies pic.twitter.com/rqKLyN4zUN

— Streetsblog New York (@StreetsblogNYC) August 2, 2018

Charles Komanoff, who argued for congestion pricing instead of an Uber-Lyft cap in a Streetsblog post earlier this week, said a cap won’t affect the availability of their services in North Brooklyn.

“If there are under-served areas, especially with the L shutdown, then owners of Uber or Lyft cars are going to lease them or rent them or share them for enough hours of the day to serve that demand,” he said.

The businesses are “thinking in isolation,” Komanoff added. “You know, ‘If we can get more cabs or Ubers or Lyft to the door of my business, than [the shutdown] would work.’ It’s not their job to consider that when everybody does that, nobody gets anywhere.”

The L train shutdown is a very real problem. But a cap on Uber and Lyft has nothing to do with it, and it’s incredibly deceptive of Lyft to turn people’s anxiety into a battering ram for their policy agenda.