What Will It Take to Rein in the MTA’s Outrageous Construction Costs?

The solution starts at the top, with Governor Cuomo and MTA leadership.

When he began looking into the MTA over the summer, New York Times reporter Brian Rosenthal didn’t set out to expose waste in the agency’s capital construction practices. Rosenthal and his colleagues simply wanted to understand why subway service was falling to pieces.

“Through the process, we heard from a lot of people that, first of all, the MTA was not spending enough on core maintenance of the system,” Rosenthal said at a TransitCenter panel last night. “And that, secondly, one of the big reasons that they were not spending enough was that they were inefficiently spending, or wasting, money on these mega-projects that were costing a tremendous amount of money.”

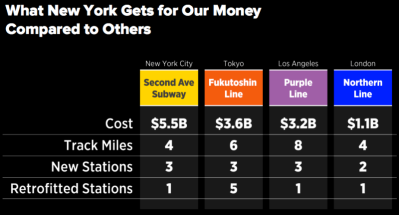

So Rosenthal started digging into mega-projects like the Second Avenue Subway and East Side Access, which cost more per mile than any other subway expansions in the world. He uncovered an array of factors driving up costs. The investigation portrays an MTA hierarchy, up to and including the governor, that’s unable — and arguably unwilling — to reform a system exploited by construction unions, contractors, and consulting firms to rake in billions of dollars.

“What we found,” Rosenthal said, “was that basically, every step of the process leads to cost increases, from the initial design of the project to the contract close-out and getting it open.”

Those conclusions are echoed in a new report from the Regional Plan Association [PDF], which outlines 11 policy measures to rein in MTA capital construction costs.

Rosenthal’s story implicates the cozy relationship between contractors and government officials in creating an environment of weak competition and lax cost control. Of the 25 top executives who left the MTA in the last two decades, the Times found that at least 17 had gone on to work for companies with MTA contracts.

Another panelist last night, Chris Ward, is familiar with both sides of these transactions. Currently an executive at engineering and construction giant AECOM, Ward’s career includes stints as executive director of the Port Authority and managing director of the General Contractors Association of New York.

Ward traced the core of the MTA’s cost problem to the lack of a “singular point of accountability and responsibility” in agency construction projects. In other words, no one has really taken charge.

During construction of East Side Access, for example, disagreements between the Long Island Railroad and Metro-North over blasting standards during excavation led to “almost two years of delays” in Ward’s estimation. Not only did that drive up costs for that project, which is now billions of dollars over budget, it also inflated costs for future MTA contracts, as construction firms priced in the uncertainty of working for the agency — the “MTA premium.”

Ward thinks reform needs to start at the MTA, not with the contractors or unions. “I think there’s a solution at hand,” he said, “but it’s a management one, and not one to be tripped up by singular examples that appear outrageous, or somehow ripping off the system, or [that] somehow the system’s rigged.”

Speaking after the event, Ward clarified that contractors and the MTA share responsibility for inflated construction costs, but that the ultimate responsibility falls on the MTA to hold its contractors accountable.

“It would be unreasonable to expect the contractors to not anticipate risk, which was created by the uncertainty within the agency in how it manages projects,” he said. “On the other hand, contractors in particular need a level of discipline in how they allocate that risk, and where it is, rather than simply saying, ‘I’m going to put a 30 percent contingency on it.'”

The MTA can impose this discipline when it negotiates. “The MTA can say, ‘We want you to put a contract bid together and we’re not just going to look at a lump sum contingency at the bottom,” Ward said. “Show us where the contract’s at risk, and if it’s at risk because of this or this or that, we’ll consider it, but if it’s just a lump sum at the bottom, you’re using that as either a boost in your overall fee or you’re hiding your own inefficiencies.”