DOT Might Widen Brooklyn Bridge Promenade, But Rules Out Claiming a Car Lane for Bikes

A cable inspection that won't wrap up until 2021 will determine whether the bridge can carry more pedestrian and bike traffic.

Sixteen months after DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg announced a study of expanding the Brooklyn Bridge’s narrow path for walking and biking, the results are finally here [PDF]. But a wider path is still at least several years away, if it proves feasible at all.

DOT intends to test the structural feasibility of a wider promenade via cable inspections scheduled to begin in 2019, a process that’s expected to take another two years to complete. Construction would take another few years.

A faster solution would be to repurpose a traffic lane for bicycling on the Brooklyn Bridge roadway, but DOT has sided against that, mainly citing traffic impacts on downtown Brooklyn. It’s exactly the type of concern that a good congestion pricing plan — which Mayor de Blasio has been resisting — would address.

Walking and biking on the Brooklyn Bridge have more than doubled over the last decade. On a typical weekday, about 10,000 pedestrians and 3,500 cyclists use the bridge path, according to DOT counts, and on most days with decent weather it is a constant contest for scraps of space.

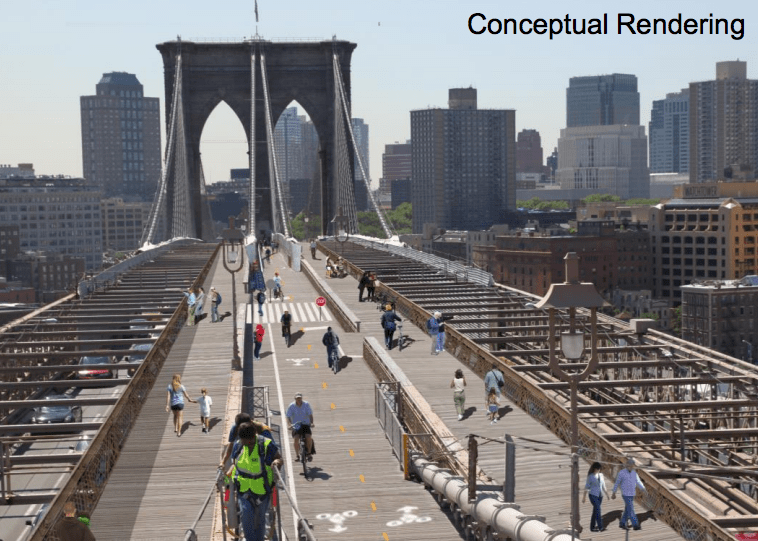

DOT is looking to widen the promenade and raise it to the grade of the girders above the roadway. The conceptual design DOT released today shows a path that’s roughly double the width of the current promenade:

A preliminary engineering study by AECOM found that the bridge can support the weight of a wider promenade but not necessarily the additional people who would use it. AECOM said a cable inspection slated for 2019 as part of planned maintenance would reveal whether the bridge can bear that weight. The inspection itself will take around two years to complete.

Speaking to reporters this afternoon, Trottenberg said construction of any promenade expansion would “probably take a couple years.” That would put completion on pace for 2023 at the earliest.

DOT does have some ideas to relieve the worst bottlenecks before then, including a bike ramp on the Manhattan side that would bypass the pinch points near the base of the path. A shuttered Park Row exit ramp could be repurposed for bikes, independently of any promenade widening (though the rendering shows it connecting to a widened path):

DOT also wants to set new rules to limit vending on the promenade, which can create intense pinch points near the Manhattan approaches, and is looking for potential nearby alternative locations for vendors.

Those spot improvements could help with the most uncomfortable crowding, but most of the bridge path will remain cramped. With a full widening of the promenade taking at least several years, the decision to rule out the conversion of a motor vehicle lane stings more.

“As someone who bikes over the Brooklyn Bridge regularly, I understand the desire to do that,” Trottenberg said. “The traffic modeling showed it produced pretty extraordinary traffic back-ups that made their way through the whole network of downtown Brooklyn.”

On the bridge roadway, she added, it “would not necessarily be that easy to create a bike lane that felt safe and enjoyable for the cyclists.”

DOT did not model a bike path on the Brooklyn-bound side of the bridge, however, which would presumably affect traffic less, since the evening rush hour is more dispersed.

Putting a price on the free Brooklyn Bridge would certainly change the equation too, but the mayor has shown no inclination to use incentives to reduce driving as a catalyst to create a safer, greener transportation system.