Christina Greer: Let’s Get Creative About Solving NYC’s Transit Affordability Crisis

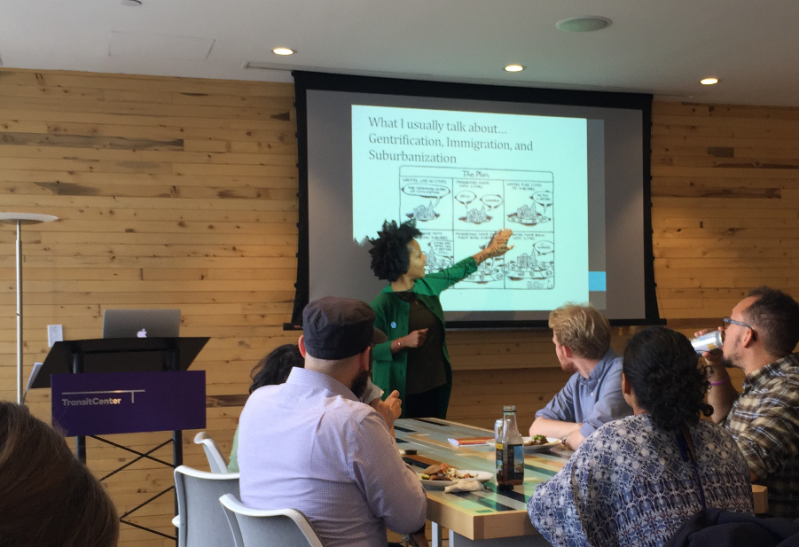

The NYC transit system is what connects residents to their city, but for many low-income New Yorkers, it simply costs too much to ride. Fordham political science professor Christina Greer thinks policy makers can help address that — if they’re willing to get creative.

A 30-day unlimited MetroCard is the best bargain for people who ride subways or buses every day, but at $121 the upfront cost is too steep for many low-income riders. Poorer New Yorkers tend to pay per ride, weighing the $2.75 price of each trip they take. Moreover, the cost of a single-ride has increased 37.5 percent since 2009 — more than double the 15 percent rate of inflation — as rising debt and fixed costs have compelled the MTA to squeeze more revenue out of riders.

For poor New Yorkers, the ability “to move about the city freely,” said Greer, is constrained by these rising costs.

“[Low income riders are] less likely to afford a monthly pass, they’re less likely to afford an automobile, they’re more likely to work farther away from home than the rest of us, and usually in another borough, and they’re more likely to work nontraditional hours,” she said.

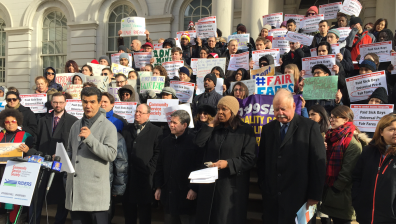

Greer isn’t a transportation policy wonk or professional transit advocate, but her interest in how city politics and policies affect marginalized communities drew her to support the “Fair Fares” campaign earlier this year.

Since the campaign launched last year, advocates have used it to raise awareness of how low-income New Yorkers struggle to afford transit, often to the point of jumping the turnstile. In 2015, there were more arrests for fare evasion in NYC than any other offense.

“I was really on board with the Fair Fares campaign,” Greer said. “We have to figure out some way to make the subway affordable to communities where $2.75 is just not feasible.”

To do that, Greer thinks policymakers have to be creative. She suggested a handful of rough concepts that could complement a Fair Fares program to improve transit access for low-income people:

- A “reverse zone system,” where people boarding in neighborhoods far from the center of the city, who typically have longer commutes, would pay less

- A sliding scale for fares

- Increasing the cost of monthly passes to equalize the financial burden on rich and poor

On that last point, a related idea that has traction in a growing number of cities is to make monthly transit costs more affordable to low-income riders via “fare caps.” The idea is that riders who buy single rides would not have to pay more in a given month once the total they spend on fares reaches a certain threshold.

Solutions are out there, it’s just a matter of acting on them. “There are a lot of excuses when it comes to trying to figure out things for the poor,” she said. “The subway’s not going to be frozen at $2.75… Now is the time to think about it, not when the subway is $4.”