How DOT Is Using Data to Perfect Its Street Safety Projects

The agency hopes a new data model will enable fine-grained analysis of how specific street design changes help prevent crashes and injuries.

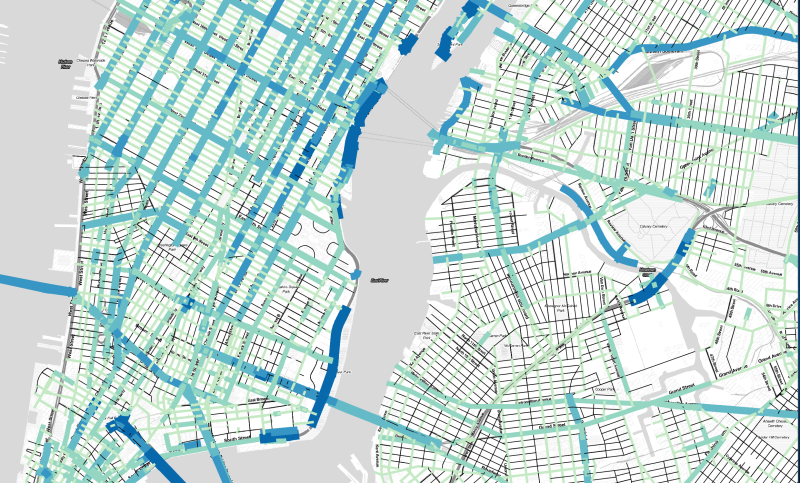

When NYC DOT planners set out to make a city street safer, they have a variety of design tools at their disposal. But it’s not always obvious which one will make the biggest impact to reduce traffic injuries and deaths. So DOT is developing a data model to provide a clear answer.

Over the last year, DOT has been working with developers at the non-profit DataKind to analyze the effects of its street safety projects. Factoring in before-and-after crash data and the design components of each project — the sidewalk extensions, signal adjustments, and other ingredients in its engineering toolkit — DOT aims to get a sharper sense of the specific effect of each component on safety.

DataKind has actually created two models. One helps DOT quickly assess the effect of a street intervention on motor vehicle traffic. Yes, this reflects the fact that the agency still factors in traffic flow when making street design decisions (which is regrettable!), but in this context, it’s a tool to accelerate safety projects.

Because DOT only has hard traffic counts for about 5 percent of city streets, currently planners go out and measure vehicle flow at the location of a redesign, a process that takes about a month. The DataKind model may make this step in the process obsolete by extrapolating traffic data for streets that haven’t been measured directly.

“That means that the planner who’s about to start working on a project… sitting at their desk they can immediately have a sense of whatever design they’re thinking about, whether it’s [viable],” said DOT Director of Safety Policy and Research Rob Viola.

The other data model aims to forecast the safety effect of a specific redesign. It’s still a work in progress, because the model doesn’t have a large enough dataset to accurately predict the safety impact of individual design elements.

“When you really chop up the [street improvement projects] into these pieces, there’s just not enough of each individual piece throughout the city for the software to figure out” their effectiveness, Viola said. “This model is getting us closer to being able to estimate when you put in a project, not only how it will affect traffic in the future, but how it will affect safety in the future.”

When the dataset is sufficiently robust, DOT will use it to evaluate projects with greater attention to detail.

Why, for example, do some protected bike lanes reduce crashes and injuries more than others [PDF]? On Eighth Avenue, where DOT installed protected bike lanes between 2008 and 2010, injuries declined 20 percent between 14th Street and 23rd Street, but only 4 percent between 23rd Street and 34th Street.

“Once we have that knowledge, that’s going to make us more precision-guided in terms of [design elements],” Viola said.