Evidence That Split-Phase Signals Are Safer Than Mixing Zones for Bike Lanes

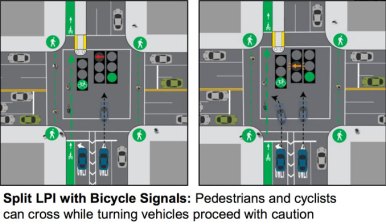

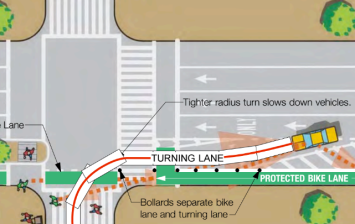

When DOT presented plans for a protected bike lane on Sixth Avenue, one point of contention was the design of intersections. How many intersections will get split-phase signals, where cyclists and pedestrians crossing the street get a separate signal phase than turning drivers? And how many will get “mixing zones,” where pedestrians and cyclists negotiate the same space as turning drivers simultaneously?

DOT tends to opt for split-phase signals only at major intersections, like where Sixth Avenue crosses 14th Street and 23rd Street. At other cross streets with turning conflicts, the mixing zone is the go-to treatment. Manhattan Community Board 4 wants to change that, asking DOT to include more intersections with dedicated crossing time for pedestrians and cyclists in the Sixth Avenue project.

The evidence backs up CB 4’s assertion that split-phase signals are safer. Data from previous protected bike lane projects in Manhattan show that the reduction in injuries on streets that mostly received split-phase treatments was more than double the improvement on streets that mostly received mixing zones.

A 2014 DOT report [PDF] analyzed three years of before and after crash data from Manhattan’s protected bike lanes. The last section of the report shows the change in total crashes with injuries on 12 protected bike lane projects — six with primarily split-phase treatments (segments of Eighth Avenue and Ninth Avenue below 23rd Street, and two unconnected segments of Broadway in Midtown), and six with primarily mixing zones (segments of First Avenue, Second Avenue, Columbus Avenue, Broadway, and Eighth Avenue above 23rd Street). We don’t have access to the raw numbers DOT worked with, but the aggregate data strongly suggests that split phase treatments are significantly safer.

On average, crashes with injuries declined 30 percent on the six “split-phase” redesigns and 13 percent on the six “mixing zone” redesigns.

On eight protected bike lane segments, DOT also analyzed cyclist injury risk, a measure that, roughly speaking, divides the number of cyclists killed or severely injured on a given street segment by the number of cyclists counted on that street. Two of those segments, on Ninth Avenue and Broadway, were primarily split-phase projects while the others were primarily mixing zone projects. While we don’t have access to DOT’s raw data, the average improvement on the split-phase segments was about 51 percent, compared to a 30 percent improvement on the mixing zone segments:

Mixing zones cost less than split-phase intersections and require removing fewer parking spaces, which means they can be implemented faster and with less pushback than split-phase intersections. In November, DOT officials also told CB 4 that they were wary that, in cutting pedestrian crossing time, split-phasing would lead to increased disregard for walk signals.

Last Wednesday, DOT came back to CB 4 without having added any split-phase intersections to the Sixth Avenue plan. The committee passed a resolution calling on DOT to install two additional split-phase signals on Sixth Avenue in the next year, and DOT’s Ted Wright said the department could study their feasibility in the future.

The data suggest that pedestrians, cyclists, and motor vehicle occupants all get a clear safety benefit from split-phase signals, however. Even if split-phase signals aren’t included in the first iteration of a project to ensure timely implementation, it should be standard practice to retrofit existing protected bike lanes with them over time. More injuries and deaths will be prevented, and more people will feel safe biking on city streets.