Study: Painted Bike Lanes Don’t Endanger Pedestrians or Anyone Else

New York City’s tabloid media simply can’t stop seeing the city’s bike boom as a mortal threat to pedestrians. Even research showing a decline in the number of bike-ped crashes was somehow spun to say the opposite, that more cyclists were hitting pedestrians than ever. Now, new peer-reviewed research confirms once again that bike lanes don’t endanger pedestrians and don’t cause more crashes. If anything, researchers say, they make streets safer.

Even though they attract more cyclists onto the street, New York City’s painted bike lanes don’t lead to any increase in the number of traffic crashes, according to a new study in the American Journal of Public Health. The study’s authors expect that if they could adequately control for increased bike traffic, the numbers would show that crash rates went down due to the installation of bike lanes.

The researchers attempted to mimic the structure of a true experiment by pairing each street with a bike lane to a street without a bike lane that was otherwise as similar as possible. They attempted to control not only for design features like the number and direction of the lanes and the presence of stop signs or traffic signals, but also contextual factors like population and retail density. That enabled them to factor out the significant increase in traffic safety that has taken place across all of New York City.

“The difference between the treatment group and the comparison group in terms of a reduction is just not significant,” author Cynthia Chen, a transportation engineer at the University of Washington, told Streetsblog. The change in the number of crashes was statistically insignificant not only for total crashes, but for vehicle crashes, bike crashes, pedestrian crashes, and crashes that caused death or serious injury.

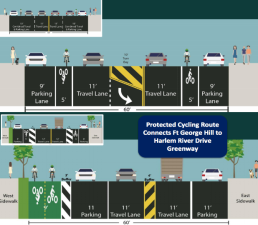

The study only looked at painted bike lanes installed in New York City between 1996 and 2006. Protected bike lanes, all of which were installed after that period, have had impressive safety results. A protected lane installed on Manhattan’s Eighth Avenue, for example, reduced injuries for all street users by 35 percent, according to DOT.

DOT’s landmark pedestrian safety study, which similarly attempted to control for confounding factors, also found that on streets with bike lanes, serious crashes were 40 percent less likely to kill victims.

Chen argued that her team would likely have found significant results if they had better data about bicycle volumes, which they believe increase after bike lanes are installed. “We think that if we were able to control the increase in bicycle volume, we would probably have found a significant reduction in crashes for the treatment group.” In other words, bike lanes might improve safety per person even if the total number of crashes holds steady.

The researchers also saw far greater numbers of bicycle crashes at intersections than on straight road segments. To improve safety, they recommended extending bike markings across intersections and installing more bike boxes.

The study, set to be released in an upcoming issue of the peer-reviewed journal, was conducted by a team of five academics and one city DOT official. DOT also funded the study.